Every night, thousands of San Franciscans have no place to sleep. And yet, every night hundreds — possibly thousands — of single-room occupancy hotel units are left empty.

According to the latest count, 4,353 people were living unsheltered in our city. Among them, 1,020 were between 18 and 24 years old. If, by some alchemy, the city could beam them into these empty rooms, the entire population of homeless youths and a decent number of older adults could be indoors by nightfall.

Why are the rooms empty? There is no one reason. Certainly, some are in no condition to be rented out. Some hotel owners are choosy when taking on what will be a rent-controlled tenant. It could take an owner months to evict the tenant if he or she stops paying rent. And, notably, others are holding rooms empty, perhaps for years, driving up the value of a building that may eventually be transformed into a high-rent, shared-living space for the city’s transcendent new residents.

That puts a crimp in the city’s plans to lease out these rooms to the needy. Over the past 20 years, San Francisco has underwritten the price of thousands of formerly homeless residents’ rooms in private hotels run by nonprofits. But now it is a seller’s market. Hotel owners can charge upward of $2,000 for rooms in hotels formerly occupied by the down and out. Other owners are holding those rooms empty, perhaps in search of an even bigger payout down the road when they sell their buildings.

See: How to Fill All the Empty SRO Rooms

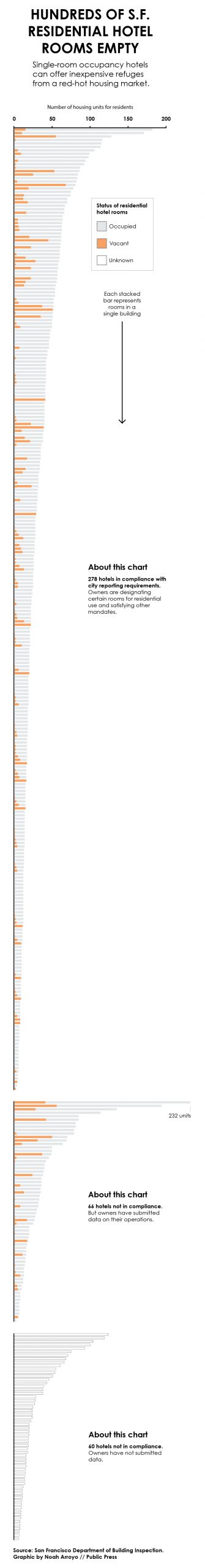

Statistics compiled by the Department of Building Inspection reveal that, as of early September, 1,827 residential rooms were known to be sitting vacant in the city’s 404 privately owned single-room occupancy hotels. That is around 14 percent of the 13,190 residential rooms available for rental in private SRO hotels — around one out of every seven. And yet this number is undoubtedly on the low side: Sixty hotels shirked their annual usage reports, offering incomplete data or none at all. There are some 1,903 residential rooms in these delinquent hotels alone. And, logically, establishments either opting to spurn the city or unable to handle reporting requirements may have much to hide. It is probable that well over 2,000 SRO residential rooms are vacant.

That an appreciable portion of the city’s private SROs ignored the mandatory reporting requirements is indicative of many things. It reveals how, prior to a law that went into effect in March of this year, the city had limited ability to compel hotels to follow the rules, or to punish those that did not. And it is also a sign of the limits of what we can glean from “submitted information.”

These are not widely circulated figures. When queried about how many vacant SRO rooms there might be in this city, Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing Deputy Director Sam Dodge and Tenderloin Housing Clinic Executive Director Randy Shaw both guessed it could be in the hundreds. Former homelessness czar Bevan Dufty estimated at least 2,000. Various private SRO owners we spoke with put the number at 2,000 to 4,000.

The city’s data were not carried down in tablet form from Mount Sinai. They are better taken broadly than narrowly; via shoddy self-reporting from the hotels or erroneous numbers input by the city — or both — not every cell on the Department of Building Inspection’s vast spreadsheet adds up. But some of the numbers are so big that they cannot help but jump out: Among the 366 private SROs with more than 10 rooms that have reported their residential vacancy rates, in accordance with city law, 23 are one-third to one-half empty and 30 are more than half empty. Of those, nine are totally empty — with 247 units lying fallow within. Owners have told the city many are being renovated or were damaged by fire.

Those are the cold, hard statistics. And, at first blush, they do not make intuitive sense. A decade ago, $400 or $500 a month could get you an SRO room. Now the average monthly rent across all hotels is $816, city data show, and almost one-fifth rent their residential rooms for over $1,000 — eclipsing, problematically, what locals receive in disability payments. At about $4,500, the rooms at 465 Grove St. are the priciest in the city. Hotel owners keeping rooms empty are doing so despite a number of people willing to pay alarming rates. And well-heeled real estate professionals are queuing up to spend serious money to get into this game. A combined property at 662 Clay and 700 Kearny streets featuring 143 SRO rooms and nine retail sites (the listing boasts a “huge upside in rents”) went on the market earlier this year for an eye-opening $19 million — nearly double the city’s assessed value for the land and structures.

“I’m an investor,” explained an SRO owner, speaking under the condition he not be quoted by name. He had recently bought into Chinatown — something non-Chinese rarely did in the past. “I’m looking at where the opportunity is to own a hotel and run a successful business.”

The average tenant in his newly obtained hotel is paying around $550 a month. Future residents will be charged nearly three times that amount. He has no desire for charity cases — and if the city or some nonprofit wants to step in and bridge the gap for homeless or indigent residents, they are looking at a steep subsidy. “Gentrification is not against the law,” he said.

The five bucks a gold miner’s blanket cost in 1851 comes out to $154 in today’s money. We have not quite doubled back to those levels of scarcity-driven rapacity — but when young, able-bodied tenants are willing to pay $2,000 (or more) to live in gussied-up SROs, and hardscrabble SRO dwellers are shelling out upward of $1,000 a month, it does not make short-term sense to hold rooms vacant.

But, in a prior, less gilded era, family-run hotels would often do just that if the owners felt they had all the tenants they could handle. Some still do this. Roger Patel, who lives in and runs the Bel-Air Hotel at 344 Jones St., nearly signed a pact with the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing that would have filled the hotel with city-funded tenants. (The department currently offers hoteliers rental rates of around $650 or $700 — sometimes even $800 — per room per month.)

Voice messages left for Patel were not returned, but multiple sources close to the deal say the hotel owner backed out when confronted with the steep up-front costs to get the Bel-Air into shape and compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act.

City records denote that 28 of the hotel’s 59 residential rooms are vacant. “There are more and more demands to upgrade the properties and some of the owners don’t have the capabilities,” explained a fellow SRO owner. “They’ve owned the buildings a long time. For them, it’s a matter of just leaving it empty.”

There may be no more extreme case of this than the Chronicle Hotel at 936 Mission St. The 156-room hotel had only three elderly tenants as of 2011, and by 2012 the Department of Building Inspection classified the hotel as “vacant.” No phone numbers listed for addresses within the building currently connect; calls to numbers listed for the branch of the Patel clan that own this building were not returned.

The Public Press spoke with multiple SRO owners who, on background, claim they have made offers on the Chronicle, which they estimate could fetch $20 million or more. But it would require significant renovations, perhaps costing upward of $10 million. The Tenderloin Housing Clinic’s Randy Shaw says that the hotel is so dilapidated and its rooms are so minuscule that it would likely have to be razed. All the bidders we contacted were rebuffed by an owner they claim would not sell at any price. “It makes me feel so bad,” said a spurned buyer. “That’s 150 units that could be put to good use.”

And, though not at the Chronicle, the city has put plenty of units to good use. Through a master-leasing program, the city has taken over 44 SROs during the past two decades and contracted nonprofits to run them. Some 4,000 units are filled with residents who could otherwise be homeless.

The most amenable owners and the most suitable hotels, however, signed on with the city eons ago. Today, SRO owners with gaudy vacancy rates are neither anachronistically naive nor bizarrely eccentric. Rather, they may be playing a game the city cannot afford to buy into.

Leaving rooms unfilled during a housing feeding frenzy does not make much sense. … Until it does.

Sam Patel grew up mopping the floors at the Apollo Hotel in the Mission District, which his parents owned and where they all lived. He remembers the day back in the mid-1970s when the letter arrived in the mail. The city was inquiring which of the hotel’s rooms were occupied by tourists or were vacant, and which were rented out to long-term tenants. “My parents thought it was just a survey,” the second-generation SRO owner said with a chuckle. “A few years later it became an ordinance.”

Based upon how hoteliers answered those queries, the resultant Residential Hotel Unit Conversion and Demolition Ordinance of 1979 declared which rooms in their hotels would be residential and which would be for tourists — permanently. Patel’s parents were honest: They wrote back that 100 percent of their rooms were rented out to long- term tenants. Four decades later, the hotel is still 100 percent residential. Had the elder Patels fudged the truth and claimed rooms were vacant or occupied by tourists, they could well have been granted entree into the more lucrative and hassle-free business of running a traditional hotel.

Tourists, unlike residents, do not tend to spend the 32 consecutive days in a room required to establish residency rights. They do not lock in rent-controlled rates that may quickly fall below market rate. They do not tend to exhibit the problematic behaviors SRO owners associate with the least desirable tenants. They, in fact, pay a far higher day-to- day rate than full-time occupants and, unlike savvy SRO dwellers, they do not tend to call the building inspectors or their district supervisor when the hot water cuts out or the trash piles up. Tourists are not a constituency.

SRO owners looking to open tourist rooms must grapple with this question: What to do with their residential rooms? Owners who convert rooms from residential to tourist use must offer the former residents replacement rooms at the same monthly rates, the city’s conversion ordinance states. This creates incentives to leave residential rooms empty.

The grandfathered, rent-controlled tenant will be a consistently weaker source of revenue than the tenant who signs the lease tomorrow at a higher price. Because the vacant rooms represent future profit, they can help an owner sell a property at top dollar. Or, if the owner buys another property to expand his or her bank of tourist rooms, many future tenants will sign leases at the prevailing rate, helping offset the costs of expansion.

Housing activists claim this is the situation underpinning multiple proposals involving largely residential SROs hoping to convert into tourist hotels by transferring hundreds of residential units into new developments. Several of the hotels sport telltale high vacancy rates. One, The Mosser Hotel at 54 4th St., reports that 68 of its 81 residential units are unoccupied.

Less dramatically, many SROs have, for years, eluded the conversion ordinance by renting out residential rooms on a weekly basis — which, obviously, catered to tourists — and shuffling around residents approaching the 32-day threshold that establishes tenancy rights in a practice called “musical rooms.” The loophole was finally closed early this year. “Long story short: You have to treat residential units like residential units,” said Supervisor Aaron Peskin, who drafted the rule change.

SRO owners’ reactions have been hostile. Several filed lawsuits against the city. Juned Usman Shaikh, the general manager of the Hotel Tropica, 663 Valencia St., wrote to Peskin ominously claiming the new law would result in a prenatal homeless program housed on-site “being stopped immediately.” City data show 22 of the Tropica’s 40 residential rooms are vacant; a call to Shaikh’s cellphone was not returned. Other SRO owners claim the law will force them to begin mandating deposits and start doing background checks — further pricing SRO rooms out of the grasp of the city’s most indigent.

It is not yet clear if stamping down weekly rentals and musical rooms will increase the real count of residential units — or have the entirely opposite effect by goading SRO owners into placing higher bars to occupancy and being pickier about whom to rent to. This will all be revealed by the forthcoming data — and hotel owners would figure to now be more forthcoming.

Peskin’s new law more than tripled a hotel’s penalty for non-reporting; it is now $1,000 a month. That comes on the heels of penalties of up to $500 a day for hotel owners turning in insufficient data; failing to maintain daily logs is also now a $500-a- day penalty. The city can subpoena SROs’ business records, recover inspection costs through liens, and — perhaps most crucially — penalize intransigent owners by limiting the number of tourist rooms they can rent out during the peak season. The Department of Building Inspection is focusing more of its attention on SRO shenanigans around vacant rooms or tourists being put up in residential units. But this is a department that eyeballs 12,000 violations a year, and its major focus will always be on habitability issues — no hot water, no electricity, no heat.

And, on top of all that, Rosemary Bosque, the city’s chief housing inspector, confirmed there is no tool, no law — no means — to compel private property owners to rent out their rooms rather than leave them vacant. Department officials simply chalked this up as the nature of private property ownership. Peskin has proposed a vacancy tax to compel landlords to put units on the market — but this remains something of a legal Hail Mary.

“We have been working on a vacancy tax since 2011,” said Supervisor Jane Kim. “It is incredibly complicated legally to enact it here as opposed to outside the U.S., like in Vancouver. Our office wasn’t able to come up with any practical legislation.”

Mrs. Zeng emptied a sack of razor clams into an eggshell blue basin and peered out the window toward the nearby homes and apartment towers protruding from the fog. It was another gray summer day, but Zeng was used to it. The elderly woman with salt-and- pepper hair has been watching the fog rolling down Russian Hill for more than 20 years from this single-room occupancy hotel at 790 Vallejo St.

Nine of the 27 rooms were reported vacant, city records show. Residents and organizers from the Chinatown Community Development Center dispute that figure: they claim 12 rooms were vacant. One, across from the third- floor kitchen, had been locked long enough that grease has congealed on the door; the carpet is movie-theater sticky and shoes make a funny noise.

“Our janitor is very lazy,” Zeng complained by way of a translator.

Every SRO has its own story, but these elements are not unique to 790 Vallejo. “We are seeing more and more vacant SRO rooms,” said Matthias Mormino, policy analyst for the Chinatown development center. His colleague, organizer Amy Dai, is in those SROs every day. “A lot of people are trying to rent vacant units, but aren’t able to find any,” she said through a translator. “And when I get into the building I see there are vacant units.”

In August of last year, the 110-year- old building was sold for $3.6 million. The vacant rooms, claims new co-owner Sam Devdhara, will be refurbished. They will likely have their own bathrooms, replacing communal commodes on each floor. He thinks they could fetch $1,000 a month. Devdhara said he “hopes to improve the place” — he has done this in other SROs — but the rent-controlled residents fear these improvements will not favor them. In 10 years, or maybe less, “there will be some turnover,” he said. “Some of these folks are looking for better and permanent housing.”

Zeng does not seem keen on moving. She went across the street to complain to the former owner at one point. But she will not do so again.

“He doesn’t care about the people in this building anymore,” she said. “He is rich.”

* * *

|

LISTEN IN: Eskenazi tells KCBS News Radio that the city could help open up rooms in SROs for the homeless by creating a hotline to report empty rooms. (10/23/17)

|

This article is part of the special report Solving Homelessness: Ideas for Ending a Crisis in the Fall 2017 print edition of the San Francisco Public Press. Order back issues here.