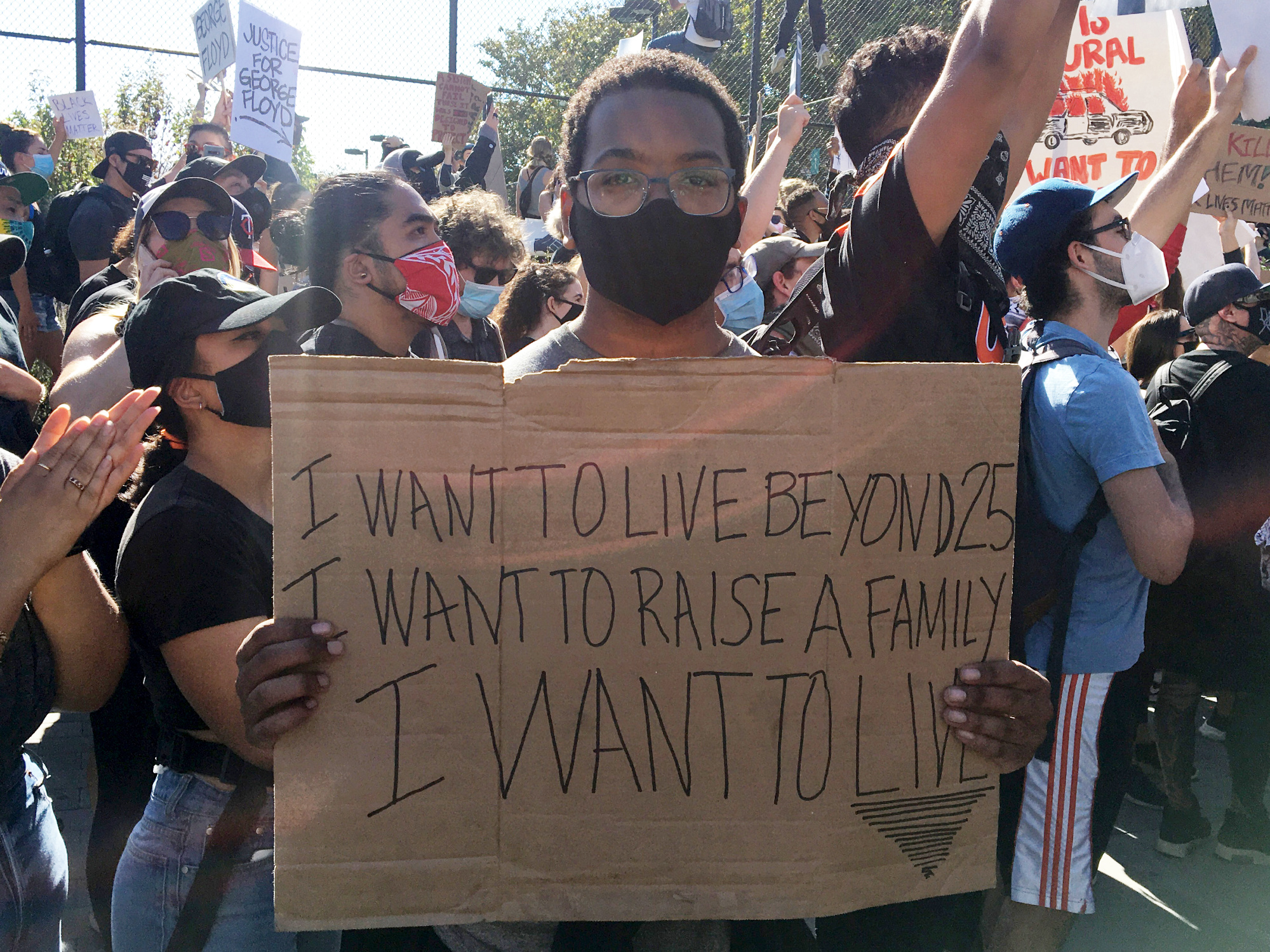

Rubin Perkins, a 21-year-old black man, joined a crowd of thousands at Mission High School on Wednesday with a sign proclaiming his demands.

“I want to live beyond 25. I want to raise a family, and I want to live,” he said, echoing his hand-lettered cardboard sign. “I don’t feel like that’s asking too much.”

Over the last 10 days, marchers thronging the streets of San Francisco to protest the police killings of black men like George Floyd and other people of color have hammered at a central theme: Their fight against racism and police brutality is a matter of survival. In conversation with the Public Press over the last week, they shared their hopes that this moment will cause lasting change, their fears that it will not and concerns about how the COVID-19 pandemic raises the stakes for speaking up in the first place.

“When white people fight the police, they can actually fight the police, they can express their anger, you know, how unhappy they are,” Perkins said. “A white person can square up with you, actually put their hands on you. I’m fighting for my life, but you still kill me. I’m on the ground, you still kill me. So that’s not OK.”

“I’m sitting behind closed doors crying, wondering if the next time I see one of my sons out, will he, too, be another hashtag?”

— Jessica, public speaker at June 1 rally

Safiya Walker, 24, who had stopped to talk to some officers as Wednesday’s march approached the Hall of Justice, said she felt an obligation to participate. As a black woman living in America, she said, she could not ignore the injustice that had been oppressing her community for generations.

“I’m living my life in San Francisco just like any other millennial who came here for a tech job, and why am I scared that I’m going to die when I see police?” she said. “I shouldn’t have to go through that. None of us should have to go through that.

“And it doesn’t matter how educated you are, or how much money you have, how much seniority or power you have,” she added. “In this country, if you’re black, you’re at risk. And that needs to stop.”

Existential fear

Many people expressed that existential fear, not only for their own well-being but that of their loved ones.

“I’m scared that I won’t be able to have a black grandchild,” said Audrey Hudson, a mother of three whose daughters had brought her to the Wednesday march.

Danielle Lickey, who lives near the route of Wednesday’s march, heard the chanting and brought her 6-year-old son to witness it, she said. She wanted him to see how many people cared about him and people who look like him.

“I want to see that my son can go to the store without feeling like he’s being watched. That he can get pulled over by the police because he forgot to put on the signal without being killed,” she said.

On Monday, hundreds gathered in front of City Hall to listen to speakers declare their solidarity and call for justice.

Jada Curry, a student at the University of San Francisco, said she worried about the safety of her family. “I even have brothers who I fear for their lives every day going outside,” she said.

“This racism has gone longer than COVID has.”

— Tirzah Love

At a demonstration Monday on the steps of City Hall, a speaker named Jessica from Fairfield who didn’t share her last name said she was frustrated by the bouts of short-lived attention the killings have sparked on social media.

“I feel like it always takes another hashtag for us to see this type of population come and join in solidarity, and it’s just not enough,” she said. “We need to know how many people are going to stand behind us in solidarity when the crowds are gone. And I’m sitting behind closed doors crying, wondering if the next time I see one of my sons out, will he, too, be another hashtag?”

Protesting during a pandemic

That urgency superseded concerns about contracting the coronavirus by joining in large crowds. While nearly all participants wore masks and social distancing was possible at some demonstrations, many demonstrators expressed both the concern about COVID-19 and a sense that those fears should take a back seat to the issue at hand.

Tirzah Love, who was not wearing a mask and recognized that social distancing was nearly impossible for her and other protesters who marched along the Great Highway on Tuesday, said that COVID-19 was not on her mind.

“You know what’s on my mind? Someone dying at the hands of the police. You know, my sister, my cousin, George Floyd, the list goes on and on,” Love said. “This racism has gone longer than COVID has.”

Melanie Tamaya and Thu Tran attended Wednesday’s youth-led protest, handing out supplies like hand sanitizer, masks and gloves.

“Black lives are in danger,” Tamaya said. “And yes, the coronavirus is out there, but I am willing to get sick and stay at home for two weeks as long as we can keep people safe — because that’s not happening right now.”

Solidarity across races

Demonstrators at all of San Francisco’s marches appeared racially diverse, and for several, it was particularly important to show solidarity against racism regardless of their own race.

“A lot of the Asian American community that I come from is either silent or complicit on a lot of anti-blackness in America,” said Maxwell Ho, marching on the Great Highway on Tuesday. “We’re no longer happy being silent on these sorts of issues. I think that we want to make a stand because the oppression of black people I think is sort of intrinsically interwoven with the oppression of all people.”

“The way we hit them is through the judicial system. The way we hit them is through the legislative system.”

— Rico Hamilton, political organizer

But the pandemic has complicated the decision to push for change. Ho said he recognized that people now had to choose between “risking your health because of coronavirus or staying home and silent and allowing those sort of police brutality incidents to continue.”

“A lot of people I’ve talked to find it difficult, especially people who live with their grandparents,” he said, or seniors who are most vulnerable to COVID-19.

Mariposa Villaluna, who is Native American and Filipino, said she decided to demonstrate at City Hall on Monday because the fates of indigenous and black people are intertwined. The Minneapolis officer who killed George Floyd was one of five officers who had been disciplined for shooting and injuring an indigenous man in 2011.

“Of course, if he thinks that he can go and kill indigenous lives, no wonder why he thinks he could go and kill and murder black lives,” Villaluna said.

Among the speakers at City Hall was Gwendolyn Woods, the mother of Mario Woods, an African American man shot by police in San Francisco’s Bayview neighborhood in 2015.

“When I watched Mario Woods’ mom talk and cry right in front of us, that really hit hard because her family was never served justice, and her son shouldn’t have deserved to die,” Villaluna said. “We aren’t that much better than what happened in Minneapolis.”

Vanessa Evers, a white nurse practitioner who attended Wednesday’s demonstration with a sign declaring that “fighting racism is essential work,” said she was working on educating herself.

“One of the things I’ve been doing that’s been helpful is trying to attend a lot of webinars online around how to be better anti-racist, and also trying to approach it as a lifelong learning and more of a practice than a checklist,” she said.

A pivotal moment?

Multiple demonstrators said that this moment felt special and unique, but they wondered if it would usher real change.

Jada Curry, the student worried about her family’s safety, decided to march because merely speaking out on social media dissatisfied her.

“To see all the hashtags on social media, it’s a start. But it’s not enough,” she said. “So physically coming out, it’s nice to see so many allies out here.” She was hopeful that the momentum would not dissipate, especially because demonstrations were occurring throughout the U.S. and around the world.

“I feel like it could be a start,” Curry said. “I really do.”

Dismantling racist power structures would be no small feat, political organizer Rico Hamilton told the crowd at Monday’s City Hall demonstration.

“It is time for us to educate ourselves. It is time for us to figure out, how do we hit them?” he said. “The way we hit them is through the judicial system. The way we hit them is through the legislative system.”

Brandon Myers, who described himself as mixed race and half black, remarked on the public’s sustained attention to the killing of George Floyd as he marched with his wife, son and more than 1,000 others along the Great Highway on Tuesday. Myers said he hoped the momentum would endure.

“This is a very traumatic experience that the United States is going through right now. And this has been the history of this country for quite some time,” he said. “At a certain point, it has to change.”

“They talk a lot about transgenerational trauma and your trauma being your children’s trauma, and getting passed on to the next generation. And it’s too late, right?” Myers said, referring to his son. “These feelings, he’s gonna feel. There’s no way around it. And my hope is that when he has kids, they don’t have to deal with it.”

— Brian Howey contributed to this story

These voices first appeared on “Civic,” the San Francisco Public Press’ local public affairs radio show and podcast. Hear those episodes: