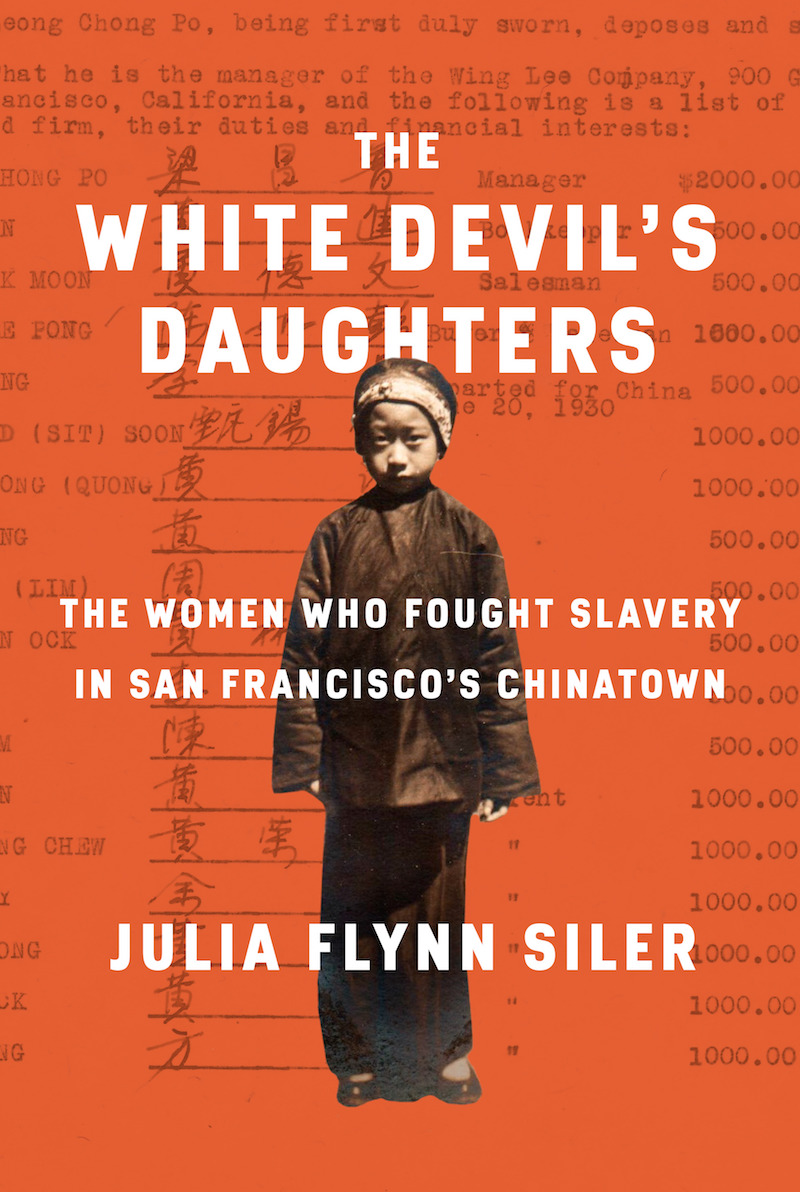

Excerpted from “The White Devil’s Daughters: The Women Who Fought Slavery in San Francisco’s Chinatown” by Julia Flynn Siler. Copyright © 2019 by Julia Flynn Siler. Excerpted with permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

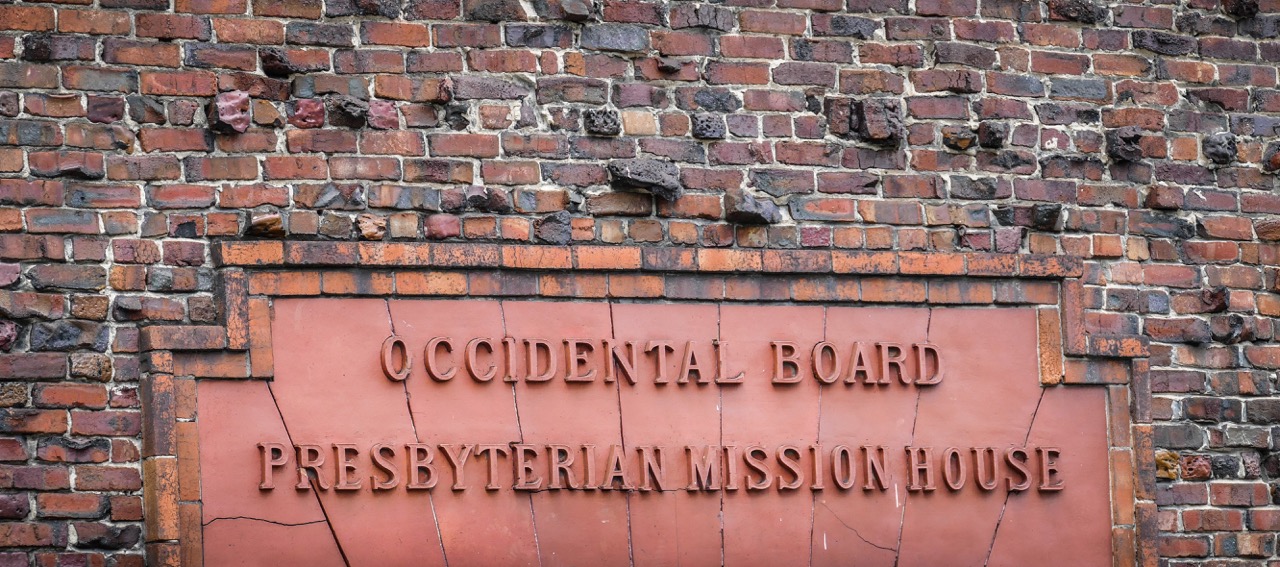

A ghost story first led me to the edge of Chinatown. One crisp morning, I dodged the crowds in Union Square and walked past a pair of stone lions up a hill. I had an address — 920 Sacramento Street — and a description. I was looking for a five-story structure built with misshapen red bricks — some salvaged from the earthquake and firestorms that razed much of the city in 1906.

Passing a church and a YMCA, I came to an old building with metal grates on its lower windows. Above the main entryway, I peered up at century-old lettering that read:

Occidental Board

Presbyterian Mission House

On a Plexiglas sign mounted onto the bricks at eye level, I read

Cameron House

Est. 1874

I climbed the steps and pressed an intercom button. A lock clicked. I pushed one of the tall doors open and walked into a dark, wood paneled foyer.

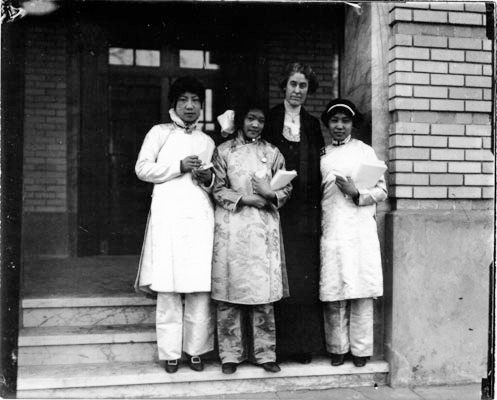

I first visited Cameron House in 2013; by then, it was mostly famous for being haunted. A staffer would later tell me he’d once sensed a ghost in its musty basement. There, he said, terrified former slaves — nearly all of them Chinese girls who’d been sold or kidnapped — had hidden in one of its dark corners from their former owners. The girls and young women had lived there under the care of two remarkable immigrant women — Donaldina Cameron, the youngest daughter of a Scottish sheep farmer, and Tien Fuh Wu, a former household slave sold by her father to pay his gambling debts. Cameron served as legal guardian to most of the girls and teens living in the home. They called her Lo Mo, or “Mother.” She, in turn, often referred to them as her daughters. But Cameron’s enemies used a racist epithet to describe her: the White Devil of Chinatown.

F or decades, Cameron and Wu engaged in what they called “rescue work”— freeing women and girls from sex slavery and other forms of bondage. An unlikely pair, they defied the conventions of their time and even, occasionally, broke laws to help other women gain their freedom. The home they ran at 920 Sacramento Street was one of the pioneering “rescue missions” in the United States, established more than a decade before the world’s first settlement house, Toynbee Hall in London’s East End, and fifteen years before Jane Addams co-founded Hull House to offer aid to Chicago’s immigrants.

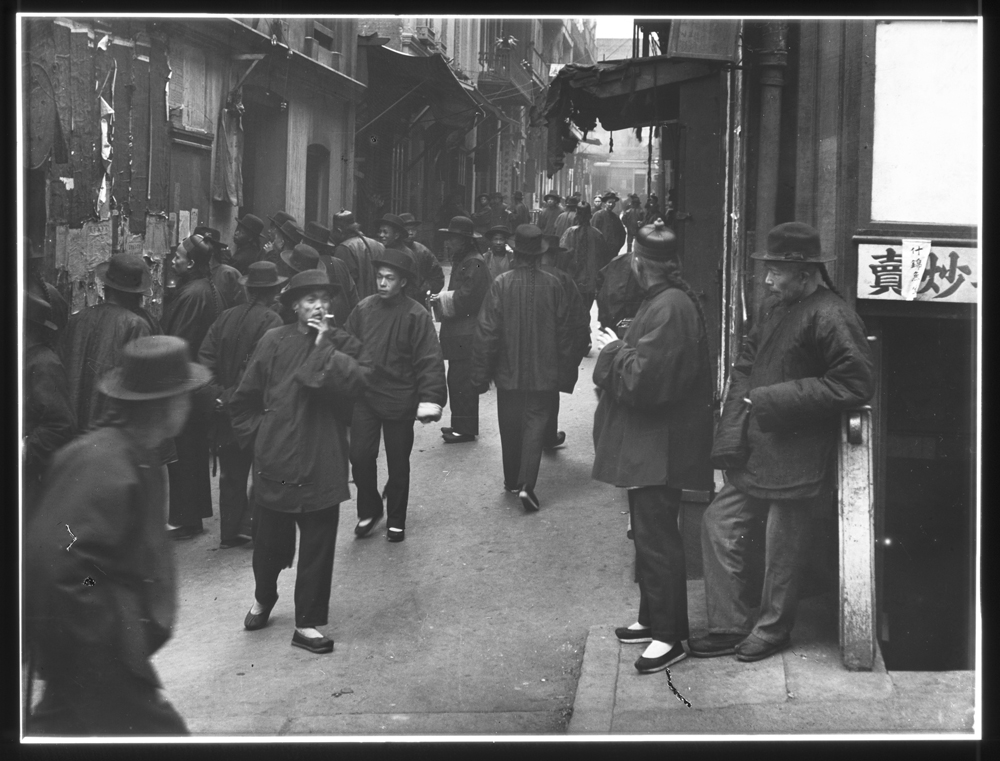

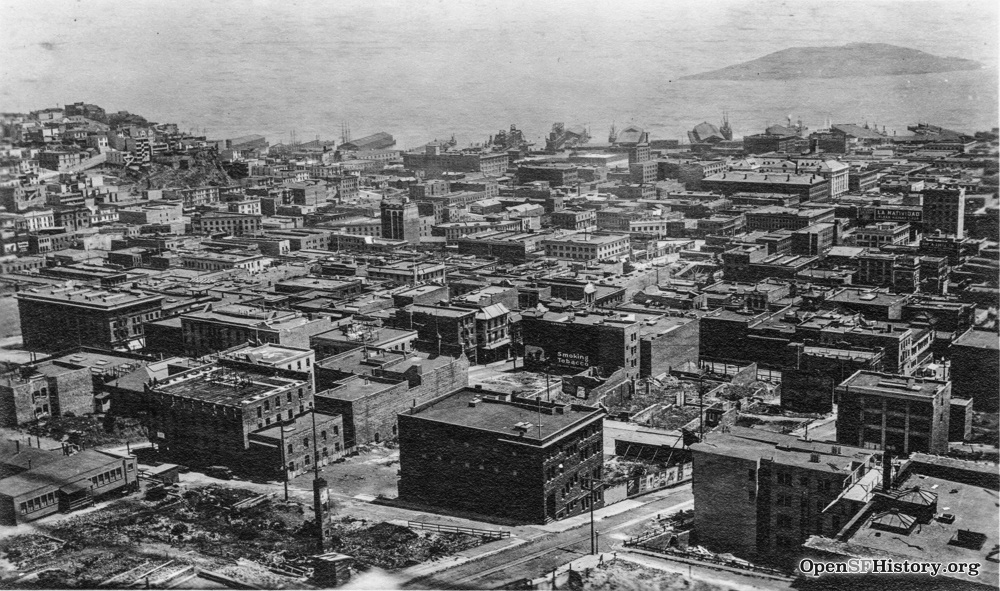

Starting in 1874, and continuing over the decades, thousands of mostly Chinese girls and women entered the home. Many came from San Francisco’s Chinatown, the ghetto of roughly eight square blocks that was North America’s largest and oldest Chinese settlement. In the latter decades of the nineteenth century, many women in Chinatown ended up working as prostitutes, some because they were tricked or sold outright by their families. They were forbidden to come and go as they pleased, and if they refused the wishes of their owners, they faced brutal punishments, even death.

From often-dusty records, I learned that the efforts of the home’s founders, Victorian-era churchwomen, with their bustles, corsets and elaborate piles of hair, were driven by compassion toward these enslaved women. They provided food, shelter and the teachings of the Christian faith to members of an embattled immigrant community who faced discrimination and violence in San Francisco and across the West. Displaying grit and ingenuity, the home’s founders overcame considerable resistance to build their rescue home at the edge of Chinatown, which was then considered by many to be the most dangerous section of the city.

Those who fled there were taking a leap of faith. The desperate conditions that led thousands of women to take shelter at the home are among the most searing stories from the saga of Chinese immigration to America. A decade after the Thirteenth Amendment abolished the slavery of African Americans, this “other slavery” — the trafficking of young Asian women — was flourishing in San Francisco and throughout the West. And because Chinatown was in the original heart of the city, this brazen trade in human flesh was taking place just a few blocks away from both San Francisco’s financial district and its most exclusive neighborhood, Nob Hill. Today, the barest outlines of these brave women’s stories fill a large bound ledger that still sits in a small, locked archive room on its top floor. In careful handwritten script, the book lists more than eight hundred names of women and girls who took refuge at the Mission Home from its founding in 1874 until January 1909. Nearly a thousand more women’s names from the decades after that are recorded in its case files. Further clues about their lives are buried in immigration records at the National Archives, and a few of its residents, such as Wu, left moving firsthand accounts.

The house at 920 Sacramento Street has a haunted history. Few people are aware of it, because human trafficking and sex slavery, until recently, have been largely unexamined corners of the American experience. Yet the story of how the home offered a gateway to so many “daughters of joy,” as prostitutes were sometimes called, is contained within the lined pages of its ledger book and offers tangible proof of the astonishing journeys these women made. They escaped their bondage, they found refuge in an ungainly brick house on Sacramento Street, and they embarked on a fight for freedom that continues today.

It was nearly dusk on December 14, 1933, when a teenage girl walked toward a hairdresser’s shop in Chinatown. Around her, laundry dangled from metal fire escapes, chickens squawked in bamboo cages on the sidewalk, and the scents of dried fish drifted through a neighborhood known as Little Canton.

Even in the depths of the Great Depression, San Francisco’s Chinese quarter drew tourists, who came to see its swaying red lanterns and taste its pork dumplings. But for Jeung Gwai Ying, who had arrived in America that summer, it was a place of degradation. For months, the teen had been imprisoned in a second-floor apartment and repeatedly raped.

So, as Jeung left the cold street and entered the warm beauty parlor with its acrid scents of perming agents and scorched hair, she hit upon a plan. She did not speak the language of the largely white world that surrounded Chinatown, but she realized that her brief outing to the hairdresser — one of the few instances when she was left to her own devices — gave her the chance she needed to escape.

Jeung’s journey to the United States had begun that summer with hope and a ruse. The people who had arranged her trip had promised her a well-paid job in San Francisco. But for more than fifty years, exclusion laws had barred most Chinese from entering the United States, so they had also given her a story about a Chinese American family she was supposedly rejoining in the States. As she crossed the Pacific aboard the SS President Cleveland, Jeung studied the more than one hundred pages of a “coaching book” containing notes on her false family’s history. When she arrived in July 1933, she flung the book into the sea, as instructed, and successfully passed through immigration by reciting the details she’d memorized.

She soon realized the job she’d expected was not waiting for her. Instead, she was led to an apartment in Chinatown and ordered to strip naked as bidders examined the swell of her breasts and the curve of her narrow hips. She had high cheekbones and full lips and looked several years younger than her real age of eighteen, making her a valuable prize. But the first set of potential buyers balked at closing a deal to purchase her, perhaps sensing she might cause them trouble.

Jeung endured the same humiliating ritual again and then for a third time. The slave trader, Wong See Duck, threatened to brutally punish or kill her if she did not act meekly and comply. If she refused to submit, he warned her that he would take her to “a very dark place.”

Reluctantly, Jeung abandoned her defiant stance. If she hadn’t, she feared she would never be able to return home to her family. The price the buyers paid for her was $4,500 — more than ten times what the procurer had given her mother in China as an advance on her supposed earnings.

Soon after her sale, Jeung was moved into a second-floor apartment on Jackson Street. Her owners, a pair of women with severely pulled-back hair and penciled brows, set about making Jeung more appealing to men in America. They outfitted her in fashionable clothes and escorted her to the beauty shop down the street, where the hairdresser bobbed her hair, tucking her black locks behind her ears. For Jeung, who was raised as a traditional Chinese girl, having her long hair cut off was the first of many violations.

Jeung’s value to her owners lay in her earning potential as a prostitute. With her bobbed hair and alluring clothes, Jeung commanded $25 a night and turned over all but $4 of her nightly earnings to her owners. Twenty-five dollars a night was a high sum in Depression-era America, where the average wage for a female garment maker was just $30 a month. Put another way, Jeung could earn more for her owners in a single evening than most women, hunched over their sewing machines in tenements throughout Chinatown, could make for themselves in weeks.

Jeung’s ostensible purpose in visiting the beauty shop that afternoon was to have her hair “marcelled,” a technique named after a French hairdresser in which waves would be pressed into her hair with a hot iron. She had been instructed to get her hair done to prepare herself for a trip later that evening to San Jose, fifty miles south of San Francisco, where she would entertain a group of men at a banquet.

Was it the thought of the long evening ahead that made her run? Did she dread the prospect of stepping into her silk gown, only to step out of it hours later, entertaining the first of one or more customers that evening? Five months pregnant, she was certainly aware of the risks to the child growing inside her.

I t was one of the few times she’d been left alone since arriving in America, and Jeung had just half an hour in the shop before one of the women would return to collect her.

The streets had darkened. The minutes passed. She had nowhere to go if she attempted to flee. If she were recaptured, she would likely be beaten as punishment or forced into a drugged passivity from which she might never escape. Slave owners intentionally spread rumors of girls who had run away from their owners to the homes in Chinatown run by missionaries, only to die of eating poisoned food there.

She urged the hairdresser to work faster by curling only the ends of her hair, hoping she could slip out of the shop before her owners came back for her. If there was a clock ticking on the wall, Jeung must have watched it with rising dread. She was calm enough to put her coat back on before leaving the shop, but she did not take the few extra seconds needed to button it up — perhaps because her swelling belly strained the fabric.

She darted south, through the crowded sidewalks of the quarter, her coat flying open. She had one goal in mind: to reach the place of safety that her owners had warned her not to go.

She ran a block and a half to a house on Washington Street with an arched brick entryway lit by a Chinese lantern. She climbed the steps and pressed the bell in hope of being let in. She arrived only to discover that she had come to the wrong place. Her fear and frustration were evident. The white woman who answered the door took pity on her and led her through the streets to the place she hoped to find.

They hurried toward Nob Hill, where the grand mansions of California’s railroad and mining barons had been replaced by hotels with names like Fairmont and Mark Hopkins. Their size and sheer opulence were almost unimaginable to a girl raised in poverty in Hong Kong. After pushing through shoppers and workers returning home, they climbed the five steps to the bolted door of 920 Sacramento Street, a squat building straddling a steep hill.

Jeung caught her breath at the entrance to the house that had served as a door to freedom for thousands of enslaved and vulnerable girls and women. To her right, heavy metal bars protected the windows. She didn’t know it at the time, but the windows of the home were barred not to keep the residents of the home inside but to prevent the women’s former owners from smashing through the glass to retrieve their human property.

By now, it was nightfall and too late to turn back. Jeung had no other options. She pushed the doorbell once and then again. The doorkeeper peered through the grated window. She saw a young Chinese woman standing outside, her coat unbuttoned despite the cold, and swung open the heavy wood doors to let her in. Two women came into the foyer to meet her. One was a white woman in her sixties with a halo of silver hair, the other a bespectacled younger woman who spoke to Jeung in Cantonese. Listening carefully to the frantic girl’s pleas, the Chinese woman translated her words into English.

“Protect me!” she cried.

The women were the home’s superintendent, Donaldina Cameron, and her longtime aide, Tien Fuh Wu, who had worked together for four decades to protect some of the city’s most scorned residents. They led Jeung to an adjoining parlor, which had a comforting Chinese carpet on the floor and Cantonese hangings on the walls. The scent of Chinese food drifted through the house. Once they were seated, Wu and Cameron gently urged the teenager: tell us your story.