An excerpt from “Habeas Data: Privacy vs. the Rise of Surveillance Tech” (Melville House, 2018)

There is one American city that is the furthest along in creating a workable solution to the current inadequacy of surveillance law: Oakland, California — which spawned rocky road ice cream, the mai tai cocktail, and the Black Panther Party. Oakland has now pushed pro-privacy public policy along an unprecedented path.

Today, Oakland’s Privacy Advisory Commission acts as a meaningful check on city agencies — most often, police — that want to acquire any kind of surveillance technology. It doesn’t matter whether a single dollar of city money is being spent — if it’s being used by a city agency, the PAC wants to know about it. The agency in question and the PAC then have to come up with a use policy for that technology and, importantly, report back at least once per year to evaluate its use.

The nine-member all-volunteer commission is headed by a charismatic, no-nonsense 40-year-old activist, Brian Hofer. During the PAC’s 2017 summer recess, Hofer laid out his story over a few pints of beer. In the span of just a few years, he has become an unlikely crusader for privacy in the Bay Area.

In July 2013, when Edward Snowden was still a fresh name, the City of Oakland formally accepted a federal grant to create something called the Domain Awareness Center. The idea was to provide a central hub for all of the city’s surveillance tools, including license plate readers, closed circuit television cameras, gunshot detection microphones and more — all in the name of protecting the Port of Oakland, the third largest on the West Coast.

Had the city council been presented with the perfunctory vote on the DAC even a month before Snowden, it likely would have breezed by without even a mention in the local newspaper. But because government snooping was on everyone’s mind, including Hofer’s, it became a controversial plan.

After reading a few back issues of the East Bay Express in January 2014, Hofer decided to attend one of the early meetings of the Oakland Privacy Working Group, largely an outgrowth of Occupy and other activists opposed to the DAC. The meeting was held at Sudoroom — then a hackerspace hosted amidst a dusty collective of offices and meeting space in downtown Oakland.

Within weeks, Hofer, who had no political connections whatsoever, had meetings scheduled with city council members and other local organizations. By September 2014, Hofer was named as the chair of the Ad Hoc Privacy Committee. In January 2016, a city law formally incorporated that Ad Hoc Privacy Committee into the PAC — each city council member couldappoint a member of their district as representatives. Hofer was its chair, representing District 3, in the northern section of the city. Hofer ended up creating the city’s privacy watchdog, simply because he cared enough to do so.

On the first Thursday of every month, the PAC meets in a small hearing room, on the ground floor of City Hall. Although there are dozens of rows of theater-style folding seats, more often than not there are more commissioners in attendance than citizens. While occasionally a few local reporters and concerned citizens are present, most of the time, the PAC plugs away quietly. Turns out, the most ambitious local privacy policy in America is slowly and quietly made amidst small printed name cards — tented in front of laptops — one agenda item at a time.

Its June 1, 2017, meeting was called to order by Hofer. He was flanked by seven fellow commissioners and two liaison positions, who do not vote.

The PAC was comprised of a wide variety of commissioners: a white law professor at the University of California, Berkeley; an African-American former OPD officer; a 25-year-old Muslim activist; an 85-year-old founder of a famed user group for the Unix operating system; a young Latino attorney; and an Iranian-American businessman and former mayoral candidate.

Professor Deirdre Mulligan, who as of September 2017 announced her intention to step down from the PAC pending a replacement, is probably the highest-profile member of the commission. Mulligan is a veteran of the privacy law community: she was the founding director of the Samuelson Clinic, a Berkeley Law clinic that focuses on technology-related cases.

“The connection between race and surveillance and policing has become more evident to people,” she told me. “It seemed like Oakland was in a good position to create some good examples. To think about how the introduction of technology would affect not just privacy, but equity and fairness issues.”

For his part, Robert Oliver tends to sit back — his eyes toggling between his black laptop and whoever in the PAC happens to be speaking. As the only Oakland native in the group, an army vet with a computer science degree from Grambling State University, and a former Oakland Police Department cop, Oliver comes to the commission with a very uniqueperspective. When uniformed officers come to speak before the PAC, Oliver doesn’t underscore that he served among them from 1998 until 2006. But he understands what a difficult job police officers are tasked with, especially in a city like Oakland, where, in recent years, there have been around 80 murders annually.

“From a beat officer point of view, who doesn’t have the life experience — and of course they’re not walking around with the benefit of case law sloshing around in their heads — they’re trying to make these decisions on the fly and still remain within the confines of the law while simultaneously trying not to get hurt or killed,” he told me over beers.

The way he sees it, Riley v. California is a “demarcation point” — the legal system is starting to figure out what the appropriate limits are. Indeed, the Supreme Court does seem to understand in a fundamental way that smartphones are substantively different from every other class of device that has come before.

Meanwhile, Reem Suleiman stands out, as she is both the youngest member of the PAC and the only Muslim. A Bakersfield native, Suleiman has been cognizant of what it means to be Muslim and American nearly her entire life. Since Sept. 11, 2001, she’s known of many instances where the FBI or other law enforcement agencies would turn up at the homes or workplaces of people she knew.

It felt like a prerequisite as a Muslim in America,” she told me at a downtown Oakland coffee shop.

After leaving home, Suleiman went to the University of California, Los Angeles, to study, where she also became a board member of the Muslim Student Association. After graduation and moving to the Bay Area, she got a job as a community organizer with Asian Law Caucus, a local advocacy group. She quickly realized thata lot of people, including her own father, take the position that if law enforcement comes to your door, you should help out as much as possible, presuming that you have nothing to hide.

Suleiman would advise people: “Never speak with them without an attorney. Ask for their business card and say that your attorney will contact them. People didn’t understand that they had a right to refuse and that they [weren’t required] to let them enter without a warrant. It could be my father-in-law. It could be my dad, it was very personal.”

This background was her foray into how government snooping could be used against Muslims like her.

“The surveillance implications aren’t even in the back of anybody’s heads,” she said. “I feel like if the public really understood the scope of this they would be outraged.”

In some ways, Lou Katz is the polar opposite of Suleiman: he’s 85, Jewish and male. But they share many of the same civil liberties concerns. In 1975, Katz founded USENIX, a well-known Unix users’ group that continues today — he’s the nerdy, lefty grandpa of the Oakland PAC. Throughout the Vietnam era, and into the post-9/11 timeframe, Katz has been concerned about government overreach.

“I was a kid in the Second World War,” he told me over coffee. “When they formed the Department of Homeland Security, the bells and sirens went off. ‘Wait a minute, this is the SS, this is the Gestapo!’ They were using the same words. They were pulling the same crap that the Nazis had pulled.

”Katz got involved as a way to potentially stop a local government program, right in his own backyard, before it got out of control.

“It’s hard to imagine a technology whose actual existence should be kept secret,” he continued. “Certainly not at the police level. I don’t know about at the NSA or CIA level, that’s a different thing. NSA’s adversary is other nation states, the adversaries in Oakland are, at worst, organized crime.”

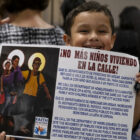

Serving alongside Katz is Raymundo Jacquez, a 32-year-old attorney with the Centro Legal de la Raza, an immigrants’ rights legal group centered in Fruitvale, a largely Latino neighborhood in East Oakland. Jacquez’s Oakland-born parents raised him in nearby Hayward with an understanding of ongoing immigrant and minority struggles. It was this upbringing that eventually made him want to be a civil rights attorney.“

This committee has taken on a different feel post-Trump,” he said. “You never know who is going to be in power and you never know what is going to happen with the data. We have to shape policies in case there is a Trump running every department.”

As of late 2017, the PAC’s most comprehensive policy success has been its stingray policy. Since the passage of the California Electronic Communications Privacy Act, California law enforcement agencies must, in nearly all cases, obtain a warrant before using them. But the Oakland Police Department must now go a few steps further: As of February 2017, stingrays can only be approved by the chief of police or the assistant chief of police. (In an emergency situation, a lieutenant or above must approve.) In either case, each use must be logged, with the name of the user, the reason and results of each use. In addition, the police must provide an annual report that describes those uses, violations of policy (alleged or confirmed), and must describe the “effectiveness of the technology in assisting in investigations based on data collected.”

Cyrus Farivar (@cfarivar) is a senior tech policy reporter at Ars Technica, and a radio producer and author. “Habeas Data” builds on his coverage by diving deep into the legal cases over the last 50 years that have had an outsized impact on surveillance and privacy law in America. Excerpt published courtesy of Melville House.