It will take at least 7 years to secure older wood buildings dangerously perched above windows or garages

One in 14 San Franciscans lives in an old building with a first floor that city inspectors say could be vulnerable to collapse if not retrofitted soon to withstand a major earthquake.

While officials have had a preliminary list of nearly 3,000 suspect properties for more than three years, they have not told landlords, leaving the estimated 58,000 residents who live there ignorant that their buildings could be unstable.

A proposal circulating in City Hall would require owners of soft-story buildings — older wood-frame structures with large windows or openings on the ground floor — to perform safety studies and retrofit if necessary. City earthquake specialists are not sharing all the details about the proposal, which they say will go before the Board of Supervisors as soon as February.

But the Loma Prieta earthquake 23 years ago showed San Francisco just how dangerous soft-story buildings are. Now the city estimates it will take at least seven more years to carry out mandatory retrofits.

Some independent earthquake safety experts say even that deadline is too optimistic, warning that the project could take a decade or longer because of a shortage of trained engineers and welders, who are busy trying to keep pace with a recent construction boom.

Laurence Kornfield, a former chief building inspector who focuses on earthquake safety for the city administrator, said safety experts lately have made great progress helping to streamline complicated retrofit standards. While he and his colleagues have felt a sense of urgency to propose the mandate, he said, “it’s better to take the time to get everyone involved than to just push stuff past” the Board of Supervisors.

Two years ago, after voters narrowly rejected a ballot measure to help soft-story owners pay for the retrofits, the idea of an unfunded retrofit mandate was put on the back burner.

But in recent conversations with banks, San Francisco has determined that landowners now have better access to private funding for the repairs than during the depths of the recession, said Patrick Otellini, the city’s newly appointed retrofit program director. Retrofits can run tens of thousands of dollars per building, and a recent city report pegged the citywide total at $260 million.

San Francisco officials said that the proposed mandate would require landlords to have the properties assessed, and would require reinforcement on the ground floor if necessary.

But in the years that officials have debated the particulars of such a mandate, city officials have left tens of thousands of residents who live in these buildings unaware that, in a major earthquake, their homes might be at high risk of collapsing onto a structurally weak first floor. Several other Bay Area cities have decided to err on the side of safety and disclose this information to owners and tenants.

William Strawn, spokesman for San Francisco’s Department of Building Inspection, said it would be irresponsible to disseminate the preliminary list of soft-story buildings because it is incomplete and imprecise, and the city has not done follow-up studies to verify whether owners have performed retrofits without telling the city. Strawn said publicizing the list “might create anxiety and alarm” where it is not warranted.

Andy Chou, a 33-year-old freelance illustrator, moved into a soft-story building in the Mission District two years ago, in what he said was a step up from his single-room occupancy hotel in the Tenderloin. His new home is in a three-story Victorian corner building with big-windowed shops below, facing the street — a classic soft-story.

Chou said that when he signed the lease, he understood that there was some safety risk. But he had no idea the city had identified the building as potentially hazardous. Last year, though, after a series of moderate-intensity quakes rattled the city, Chou and his neighbors made it a morbid running joke. “We’d talk about how this place would just go under,” he said.

A major quake, of course, can strike San Francisco at any time. There is roughly a 28 percent chance that an earthquake of at least magnitude-6.7 will hit the Bay Area within 10 years, said Edward Field, leader of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Working Group on California Earthquake Probabilities.

Critics are on edge about the city’s lack of a soft-story policy. Debra Walker, a member of the Building Inspection Commission who has worked for years on earthquake safety studies, said she is worried that technical debates will lead to further delays in getting a mandatory retrofit proposal to the supervisors.

“We’ve been having the same conversation about seismic standards and funding for two years,” said Walker, who is also a board member of the San Francisco Planning and Urban Research Association. “We have what we need. So then, let’s do it. Now. Next week.”

NO QUICK FIX

There’s a dark side to San Francisco’s rich architecture — the rows of Victorian era wood-frame buildings with their famous bay windows. Many of these apartment buildings were constructed in the early 1900s, before earthquake engineering became an established science.

Many of these buildings have big windows or glass-fronted retail shops on the ground floor. Others have had multi-car garages carved into them. These openings eliminate load-bearing walls and leave the ground floor “soft” and susceptible to collapse beneath the rest of the building.

All of the seven Marina District buildings that collapsed in 1989’s magnitude-6.9 Loma Prieta quake were soft-story. “These buildings are really vulnerable, and some are exceptionally vulnerable,” said Tom Tobin, president of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, which is headquartered in Oakland. As opposed to other structural categories, soft-story buildings are “easy and cost-effective to make safer,” concluded a study by the Applied Technology Council, a Redwood City-based nonprofit structural engineering research organization.

But until now, San Francisco has offered only a voluntary program that gives building owners a modest break on permit fees. Only 53 building owners have completed retrofits under this initiative. At the average rate of 15 projects a year since 2009, the voluntary program would take 195 years to retrofit all the problematic soft-story structures that the city has identified so far. Because the city’s survey was so rough, it could be that there are more, or fewer, soft-story buildings in need of retrofit work.

In October, the city hired what might be called an earthquake retrofit czar. Patrick Otellini, 32, spent the last decade working as a consultant for some of the city’s largest landowners at A.R. Sanchez-Corea and Associates. His job was to save clients time and money by expediting permits with the Department of Building Inspection and other city agencies. Major projects included the Four Seasons Hotel, the Main Branch Library, San Francisco International Airport, the Asian Art Museum and the Ferry Building.

His new job as a special assistant in the City Administrator’s Office pays $138,000 a year — a $42,000 step up from his old salary.

Now Otellini is in charge of writing the regulations. Kornfield said Otellini would succeed at pushing a mandatory retrofit program through the Board of Supervisors because of his extensive experience and business connections. “He knows the financiers, the contractors, the city,” Kornfield said.

Otellini said a draft ordinance mandating that owners retrofit soft-story buildings was circulating around the City Administrator’s Office before he arrived this fall, and as of early December was being reviewed by the City Attorney’s Office. “It’s largely complete,” he said.

But when asked for a copy of the draft law, Otellini declined to provide it. The reason: the document was exempt from public disclosure because of attorney-client privilege.

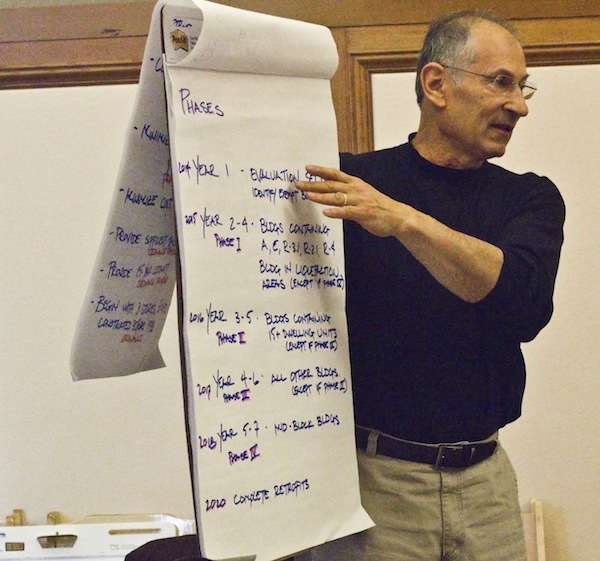

But Otellini did describe the proposed ordinance’s broad outlines. He said it would require soft-story building owners to hire a certified engineer or architect to perform an inspection and determine whether structural strengthening is needed. If an inspection finds the building lacking, the owner would have to invest in a retrofit. Retrofit schedules would be tiered for the next seven years, he said, with the most vulnerable buildings having earlier deadlines.

While no city grants or loans are currently available, Otellini said his office was still considering whether to identify sources of funding — though that might come after the legislation is publicly unveiled. One potential financial incentive under consideration, he said, is to raise the property tax rate on parcels with soft-story buildings, and then provide that money back to the building owners in the form of grants or loans when they make retrofits.

David Chiu, president of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, said he would make the proposal from the City Administrator’s Office a high priority. “I believe we absolutely need to address the plight of thousands of soft-story buildings,” Chiu said.

Chiu appeared at a City Hall meeting on Dec. 3 with the retrofit team to urge them to bring their proposal to the board without further delay. But even if it passes quickly, the last retrofits would not be done before 2020.

Some experts said even that goal was unrealistic.

Independent structural engineer Patrick Buscovich said the shortage of skilled labor could push back the retrofit timeline to at least a decade. “There’s a lot of these buildings,” he said. “You can only do so many buildings per year. There’s only so many engineers, so many contractors.”

Michael Theriault, an ironworker who is secretary-treasurer of the San Francisco Building and Construction Trades Council, said the city’s seven-year timetable would happen only “if you were able to build constantly.”

Theriault, a former Building Inspection Commission member, puts the date of completion even further out. “It could take 20 years,” he said. “I think that’s easily possible.”

Over that time, said Field of the U.S. Geological Survey, the chance of an earthquake is about 48 percent. Soft-story retrofits require specialized, certified steel welders who Theriault said are currently in high demand as several hundred construction projects ramp up. Some are massive: the new 49er’s stadium in Santa Clara, Apple’s new campus in Cupertino and the ongoing Bay Bridge East Span project. “The union halls are virtually empty,” he said.

Kornfield said skilled labor would not dry up because the Bay Area “is one of the centers of structural engineering in the country.” Most of the work, he added, can be done by general contractors.

S.F. HAS MIXED RECORD

San Francisco has scored some big successes in preparing vulnerable buildings for the next major shaking event.

In 1994, voters passed a $350 million bond measure to help finance the mandatory seismic retrofitting of about 2,000 unreinforced masonry buildings. The measure went beyond requirements of a 1986 state law that merely required cities to inventory their stock of brick structures. To date, 95 percent of these buildings in San Francisco have been retrofitted, Kornfield said. At the time, the city considered it essential to use the bond funds to provide low-interest loans to owners. But $280 million went unused because interest rates from banks were even lower.

For high-rise office towers, building codes now require new construction to be able to withstand a major earthquake, and to have elevator banks that are sturdy enough to allow use by firefighters even if the building is on fire.

Some building types are harder to fix, or even identify. Nonductile concrete structures — usually offices and light industry — are tricky to diagnose without an engineer poring over blueprints to determine whether the columns contain steel. A 2011 study estimated that San Francisco had roughly 3,000 of these buildings, and building officials have no prescription for them yet.

Soft-story buildings are far easier to address. According to Kornfield, the city’s current draft ordinance will require owners to retrofit the first, “soft” floor, but not the rest of the building. This might involve anchoring the wood frame to the foundation, or reinforcing the first floor with a steel frame.

So why hasn’t San Francisco required landlords to fix the problem? Part of the reason is that, unlike with unreinforced masonry buildings, the state does not require cities to even catalogue their soft-story buildings. Section 19160 of the California Health and Safety Code only encourages local governments to identify their problematic soft-story buildings and adopt programs to “reduce unacceptable hazards” by 2020.

No “cookbook recipe” exists for retrofitting these buildings, said Thor Matteson, a structural engineer who evaluates and designs soft-story retrofits in San Francisco. The amount and type of strengthening depends on soil type underneath the building, whether there is water or termite damage, or whether contractors had previously attempted partial reinforcements.

San Francisco has yet to do what more than half the cities in the Bay Area have done — establish some policy to prod owners of soft-story apartment buildings to retrofit or warn tenants if they have not. Some Bay Area cities have not waited for strong guidance from the state. Several cities near the active Hayward Fault in the East Bay — Berkeley, Alameda, San Leandro and Fremont — require building owners to inform tenants whether they have retrofitted their buildings. Alameda and Fremont have gone a step further, forcing owners of multi-unit residential buildings to do the retrofits or face fines.

Berkeley requires soft-story building owners with five or more apartments to hire an engineer to do an earthquake safety evaluation. Now the City Council is considering an ordinance to mandate that owners retrofit buildings that fail inspection.

John Paxton, a real estate consultant who served on a long-running San Francisco earthquake safety study committee, called Berkeley’s approach “ahead of the curve” in the region.

RESIDENTS UNINFORMED

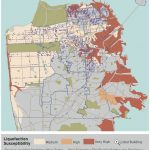

In 2007, a team of earthquake engineers from several city and state agencies launched a sidewalk survey of wood-frame properties in San Francisco with at least three floors and five apartments built before 1973 — the year the city changed its building codes to prevent soft-story weakness.

The survey was completed in 2009. Of 4,573 buildings examined, the team located 2,929 properties that had potentially dangerous configurations on the first floor, with windows, garages or other openings making up 80 percent of one outer wall, or 50 percent of two walls.

San Francisco has more soft-story buildings than any other Bay Area city, and they can be found in almost every neighborhood. The survey team found that 90 percent of these buildings are rental properties, where residents have little say in retrofit decisions. Though the list is not exactly secret, it has not been posted on any city website. Strawn, from the Department of Building Inspection, said doing so “might create anxiety and alarm, when there really isn’t a basis for it.”

Kornfield added that the survey team created the list “for the purpose of diagnosing the scope of the problem. It does not, in any way, say, ‘here are the soft-story buildings.’” The list isn’t definitive, because some buildings might contain interior load-bearing walls not visible to the staff surveying from the outside.

But officials in other jurisdictions concluded that the perfect is the enemy of the good and opted for public disclosure first.

Armed with a similarly approximate list of soft-story buildings, Berkeley in 2005 passed an ordinance forcing owners of the listed buildings to notify their tenants in writing that they might be in danger. Owners also had to post a large-print notice in a conspicuous place within five feet of the main entrance: “Earthquake Warning. This is a soft story building with a soft, weak, or open front ground floor. You may not be safe inside or near such buildings during an earthquake.”

Before removing signs, owners have to prove their buildings are not dangerous. If they do not get an engineer’s evaluation within two years, the city can declare the property a public nuisance, and can even tear it down.

City officials say the public shaming puts market pressure on landlords.

“I can tell you, there are some tenants that will not rent an apartment in a soft-story building,” said Berkeley councilmember Laurie Capitelli. “They will go somewhere else.”

Owners got the message. As of 2011, the owners of 77 percent of the 320 buildings on Berkeley’s list had at least begun the evaluation process. Twenty-eight percent of those either are now retrofitting or already finished.

Of the total number of properties on the list, 58 percent were soft-story, in need of retrofit. If the same proportion of San Francisco’s own estimate turned out to be unsafe, that would mean 39,000 tenants would be in harm’s way.

The city of Alameda passed its law in 2009 to establish an inventory of soft story buildings. It posted its list of suspected soft-story buildings on its website. Owners had to warn tenants that they might be in danger, with similar posted warning signs and written notices — until they could get an engineer to prove their building was not hazardous. Owners who failed to comply within 18 months could not legally rent out the building or even occupy it themselves.

But David Bonowitz, an engineer who represented the Structural Engineers Association of North America on San Francisco’s ongoing soft-story study, said San Francisco’s challenge is the scale of its soft-story problem.

“Berkeley could do what it did only because the city is small and the number of buildings is low,” he said, adding that the process there was messier than it needed to be. “They have a lot of false negatives and false positives.”

Because it the public has a right to access public information, and also because other cities have disclosed similar lists apparently without causing harm, the San Francisco Public Press has published the full list of the San Francisco addresses at possible risk, along with a map showing their distribution throughout the city, in the Winter 2012-2013 edition of the newspaper.

POLITICS, RECESSION SLOWED PROGRESS

San Francisco began a comprehensive earthquake safety study in 1998 during the administration of Mayor Willie Brown. The Community Action Plan for Seismic Safety did complete a proposal for soft-story retrofits — 12 years later. The report concluded that older wood-frame soft-story buildings “would be seriously damaged” in a major earthquake and “a significant number could collapse.”

Otellini and Kornfield said their new legislation would be based largely on that plan.

The decade-plus delay was due partly to disbanding of the workgroup between 2003 and 2007, when the Building Inspection Commission suspended its funding. At the time, the Department of Building Inspection’s annual budget surplus fell by 78 percent from when it launched the workgroup, to $3 million.

Among the committee’s biggest critics was Brown ally Joe O’Donoghue, then president of the Residential Builders Association of San Francisco. He said in public hearings that the Community Action Plan for Seismic Safety was unproductive because it would produce information the city already had.

The final 2010 study, which cost more than $700,000 to complete, developed a broad set of policies to help the city prepare its privately owned buildings for the next major quake.

In 2008, then-Mayor Gavin Newsom ordered the study team to fast-track research on soft-story buildings, said Paxton, “so that he could push forward some legislation and get moving on that.”

Had it passed, the fall 2010 ballot measure would have issued more than $46 million in bonds to provide grants and low-interest loans to landlords for soft-story retrofits. The idea at the time, Kornfield said, was to pass a soft-story retrofit mandate swiftly on the heels of that victory. But the measure got 63 percent of the vote — painfully short of the 66.7 percent supermajority needed to pass a revenue bond measure.

Newly appointed earthquake czar Otellini served on a committee Newsom set up after the 2010 report — the Soft-Story Task Force. Otellini said the combination of the measure’s failure and the collapse of real estate value stopped the city from moving forward.

“When the task force concluded two years ago,” he said, “we were not in an economic climate to do this, since it was the worst recession we’ve had in 50 years.”

Danielle Hutchings Mieler, coordinator of the earthquake and hazards program at the Association of Bay Area Governments, said cities have been loath to pass ordinances that could push recession-buffeted building owners into insolvency.

But now locally, at least, the recession appears to be lifting. By October 2012, a boom in the technology sector drove San Francisco’s unemployment rate down to 7.8 percent — a decline of 2.6 points from the height of the recession, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. As tech workers moved in, apartment vacancies dropped. In July 2012, average rents had risen to $2,734, an increase of 12.9 percent, according to the real estate research firm Real Facts.

This time, the city envisions that the private sector will finance most of the soft-story retrofits. Retrofitting a typical four-floor, five-dwelling-unit soft-story apartment building in San Francisco would cost about $60,000, according to several estimates. With the property prices high, the loan-to-value ratio would be attractive to banks, for typical buildings valued in the $5 million to $7 million range, Otellini said.

But officials are well aware that some of the soft-story building stock is considered affordable housing and in low-income neighborhoods, he said. So the city expects to offer financial assistance in some circumstances, he said.

With a soft-story retrofit mandate slated to be rolled out in early 2013, San Francisco officials say the city will soon become a leader in the field. Otellini said he believed San Francisco would be the first major city to mandate soft-story retrofits on multi-unit buildings.

“The earthquake engineering world is very excited to see this thing succeed,” he said. “So, at the end of the day, it is very important to do this correctly.”

But Walker said she is tired of all the waiting: “Each day we don’t do this, knowing what we know, we’re putting so many people’s lives at risk.”

This story appeared in the Winter 2012-2013 print edition of the San Francisco Public Press.