Federal affordability scale falls far short of helping thousands pay for coverage

The cost of living in San Francisco is so distorted that several thousand city residents who became eligible for health insurance subsidies under the Affordable Care Act almost two years ago still go without insurance, forgo care they need, or use free services intended for the poor.

They make too much to qualify for Medi-Cal or the city’s Healthy San Francisco program but not enough to afford the premiums, deductibles and co-pays for plans under Covered California, the state’s new program adopted under the Affordable Care Act.

New federal data show that people nationwide are in this bind. But the scale the federal government uses to measure affordability is especially inapplicable to San Francisco, ranked the third-most-expensive place to live in the world.

To help offset that imbalance, San Francisco is offering a new, subsidized plan and expanding Healthy San Francisco to bridge the gap for city residents caught between the need for health insurance and their ability to afford it.

Covered California premiums are relatively affordable. The cheapest one for single San Franciscans earning $58,850 — the cutoff for the new city subsidy — would cost roughly $202 a month. But the cheapest plans have the highest deductibles, out-of-pocket expenses for doctor visits, hospital stays and drug prescriptions, potentially totaling thousands of dollars per year. And the subsidies for these expenses that are available in states with market exchanges, like California, come only with plans on the costlier “silver” tier. As a result, many residents choose to remain uninsured, said Colleen Chawla, deputy director of health at the San Francisco Public Health Department.

Richard Gibbs, president of the San Francisco Free Clinic

This means people eligible for Covered California are turning to clinics intended for people who can’t get insurance at all or who have Medi-Cal, the state’s version of free medical insurance for very low-income residents.

“We have as many patients as ever,” said Richard Gibbs, the president of the San Francisco Free Clinic. “We’re here to catch them, and they’re still falling through the cracks.”

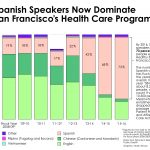

San Francisco often takes the lead nationwide with social programs because of the city’s values, said Anthony Wright, executive director of Health Access, a consumer health care advocacy group in Sacramento that backed San Francisco’s plans. And the adoption in 2007 of Healthy San Francisco, which provides free care inside the city for poor residents who don’t qualify for any subsidies, was supposed to ensure that all San Franciscans got the care they needed. So far, the Public Health Department has spent more than $885 million on Healthy San Francisco alone, and even more on other health care programs.

But the rising cost of living has stayed several steps ahead of San Francisco’s best efforts to fight it. Responding to this reality, San Francisco’s Department of Public Health is rolling out two programs in 2016 for working people who fit three criteria: they are eligible for the Covered California plan; they make less than five times the federal poverty level ($58,850 for a single person, for example, or $121,250 for a family of four); and they work for employers that pay into a city-mandated health insurance account instead of offering insurance as an employee benefit.

One program, Bridge to Coverage, will help these low- and moderate-income residents pay their Covered California premiums using funds from the city’s employer health insurance account. The city expects 3,000 people to enroll the first year and 1,000 more by 2020, and it expects the program to cost $8 million the first year.

The second program would allow those same residents to choose free care under Healthy San Francisco by expanding the income ceiling. That could help people caught in the middle, such as workers who are self-employed. Although some self-employed people can write off health care costs when they file their taxes, they still have to pay the premiums, deductibles and co-pays out of pocket before receiving a tax credit months down the road. Importantly, users will still have to pay a fine under the Affordable Care Act for not having health insurance because Healthy San Francisco provides only care; it is not insurance. The Public Health Department does not expect many people to opt for either program, which the city is calling “affordability extensions.”

And it is not clear whether either break would be enough to shield people from the pressure that housing and other costs are putting on residents. At least one nonprofit clinic is asking how long it should — or can — keep operating in this climate. The rising cost of living has led many patients of the Native American Health Center to move out of San Francisco, said the center’s strategy director, D’Shane Barnett.

“The Affordable Care Act has done a lot for our clients,” he said. “The cost of living, on the other hand, is pushing them out of San Francisco. So it doesn’t matter how good it is.”

San Francisco’s high cost of living is even pushing out the clinic’s modestly paid staffers. Two have moved across the bay. One now commutes from Newark, near Fremont, and another moved to San Leandro. If free and low-cost clinics close, it could weaken the safety net that took San Francisco decades to build — and that the Affordable Care Act promised to strengthen.

“We have to make a decision about whether we stay here,” Barnett said. “But we need to make sure we’re making a decision in the community’s best interest not just 12 months from now but 10 years from now.”

This article is part of a special reporting project on the cost of living in the Winter 2016 print edition of the Public Press.