UPDATE, March 21: The University of California-San Francisco met with community groups on Feb. 22, offering ways to offset the local impacts of their proposed mental health clinic and student housing projects. Those offers included funding a new bike route and a traffic signal, contributing to a fund for open space, and decorating sidewalks.

Community groups responded with disappointment and outrage. They said the offers were meager and would not benefit the neighborhood as a whole, even though the projects’ impacts would be widespread. UCSF Vice Chancellor Barbara French said the university would make additional offers at the next meeting, on April 24, and current offers could shift in response to the new input.

Looking to improve the quality of daily life in Mission Bay, local groups are pressing for more bike lanes, new bus routes and more green space as the city’s newest neighborhood grows.

Rather than lobby developers or City Hall, residents want the area’s dominant presence — the University of California-San Francisco — to help pick up the tab, which could be tens of millions of dollars.

UCSF will soon expand its Mission Bay campus, further crowding streets and public transit. Normally, the city would charge a private developer tens of millions of dollars in fees and taxes to pay for offsetting the long-term impact of the construction — more traffic, less parking and crowded public buses and streetcars. But because UCSF is a public institution, it is exempt from such levies. It also pays no property taxes, like all government entities and nonprofit organizations.

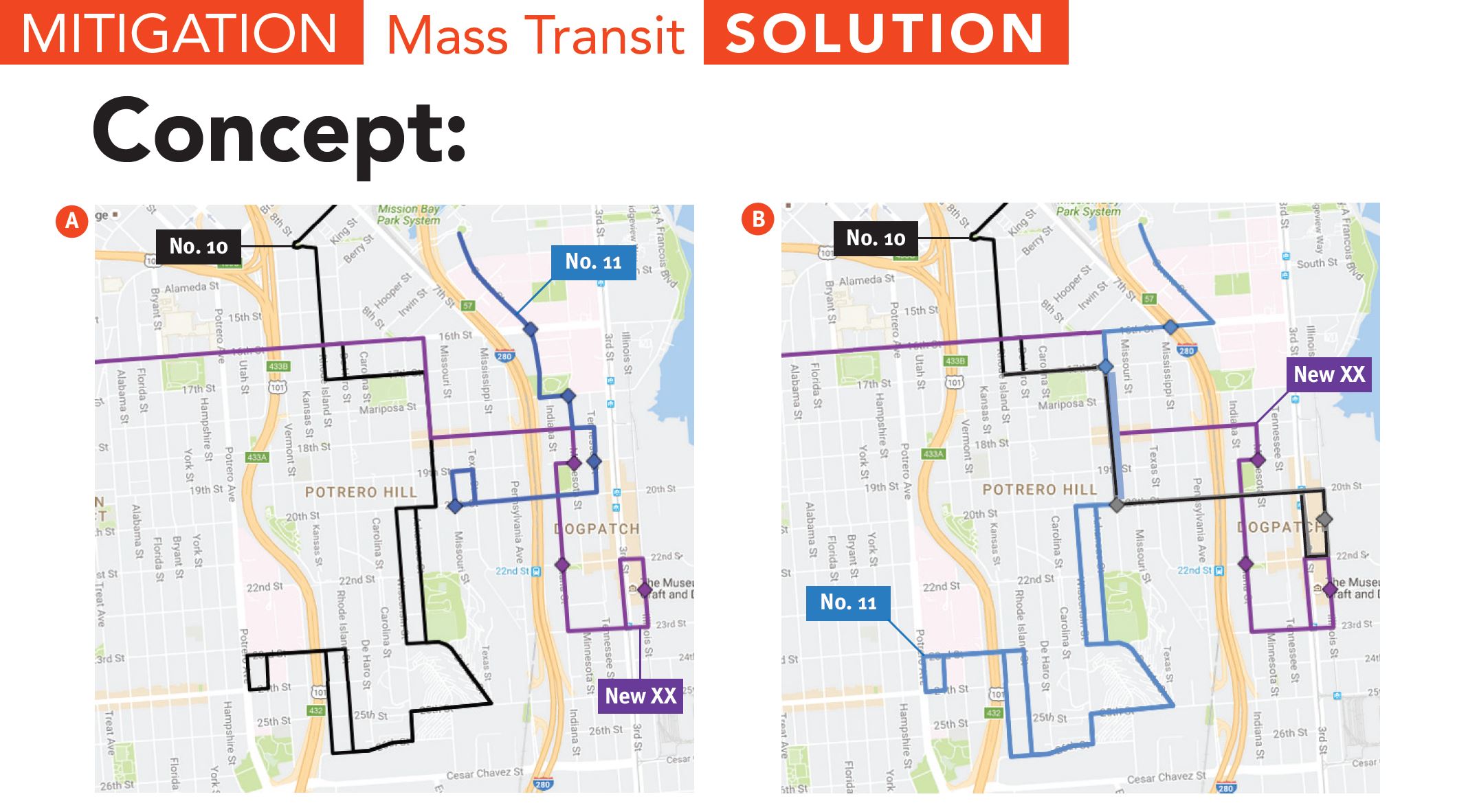

Residents of Dogpatch want better Muni service, more parkland, a community center and parking structures to relieve the daily scramble for streetside spaces. Top on the list: more buses.

“We want two bus lines. At least,” said Tony Kelly, president of the Potrero Hill Democratic Club.

The community also wants UCSF to help pay for new bike routes that would better connect Potrero Hill, the Dogpatch, Mission and Bayview neighborhoods to each other.

Since September, the Dogpatch Community Task Force — community groups and staff from UCSF and City Hall agencies — have met monthly to find agreement.

The university will respond with “a comprehensive offer” at the next public meeting, Wednesday at 6:30 p.m. in Genentech Hall at UCSF’s Mission Bay campus, said Barbara French, vice chancellor for strategic communications and university relations. She declined to provide details, but said that the task force would be able to “help to shape the final plan.”

French has implied that some requests might not be granted because they would constitute misuses of taxpayer dollars.

“Any allocation of funds beyond our public or educational mission must have a benefit also to us, or else we run the risk of a gifting of public funds,” she said at the task force’s January meeting. She noted that the university receives 3 percent of its funding from the state and 1 percent from tuition.

The university is a global research leader with top medical and pharmacy schools. Its Mission Bay campus features a state-of-the-art medical center, including UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital.

More than 43,000 people work at UCSF, making it San Francisco’s second largest employer. Besides Mission Bay, the university has clinical sites at Parnassus and Mount Zion, and operates other facilities throughout the city. The university ranked third nationwide among graduate schools of medicine in a 2016 survey by U.S. News & World Report. In January, the university received a single donation of $500 million, boosting its endowment to $2.75 billion.

At the turn of the century, the city negotiated with the university to settle in the area, hoping its presence would encourage other development. The plan worked, helping transform the eastern neighborhoods into prime territory for professionals to live, work and play.

Today, the school plans to build graduate student and trainee housing, as well as retail and parking, at 560, 590 and 600 Minnesota St.; outpatient mental health clinics at 2130 Mariposa St.; and either student housing or a medical center at 777 Third St.

In an attempt to frame the task force’s discussions over what the university should offer, Supervisor Malia Cohen directed the San Francisco Budget and Legislative Analyst’s Office to estimate how much City Hall theoretically would have earned in fees and taxes from those projects if the developer were not exempt from paying them.

The office’s report, published in November, estimated that the city would have profited about $20.8 million in one-time revenue, and $4 million annually, at the high end; low-end estimates were for about $14.8 million in one-time revenue and $2.5 million annually. Total revenue would be determined by the sizes of the buildings, which would affect forgone property taxes, as well as whether 777 Mariposa St. would be used for housing or offices.

Eastern Neighborhood Infrastructure Impact Fees would have accounted for $13.7 million to $19.7 million, which would be spent in the district to develop recreational facilities, childcare facilities, open space, or transit and streetscape improvements.

French said the report would not influence the university’s offer.

“Any discussion around a property tax analysis gets absolutely no traction,” she said. “It’s the electric third rail, if you will.”

At least one community organization is considering pushing back if that offer does not satisfy them. “It’s likely that we would consider some sort of political activity,” said J.R. Eppler, president of the Potrero Boosters Neighborhood Association.

In some ways, the area is still adjusting to the arrival of its outsized neighbor. “It was a quiet little neighborhood. And now it’s pandemonium, at times, because everybody’s in a hurry,” said John deCastro, a member of Potrero Hill’s Boosters Neighborhood Association who has lived in the area for 38 years.

Because of inadequate public transit, deCastro said, newcomers commute by car, causing two main problems: clogged streets as drivers head to and from Highway 101 and Interstate 280, and a scarcity of street parking.

And that’s a problem for an area where the residents, too, must rely on cars because of a dearth of nearby stores, said task force member Heidi Dunkelgod. “We have really great restaurants and a few boutiques, but as far as getting ordinary stuff done — bank, pharmacy, grocery store — not so much,” she said.

For the past year, the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency has been talking with eastern neighborhood community groups about adding two bus routes, Eppler said. The Dogpatch Community Task Force has proposed that UCSF work with the transit agency to get the lines running as soon as possible. That might mean retooling the current 10-line, which connects the Pacific Heights neighborhood to Potrero Hill, with the university helping the city to cover any additional costs.

Right now, the neighborhood must rely heavily on the T-Third Street light rail, which runs north along Third Street from Sunnydale Station at the city’s southeastern corner, then turns into the westbound K-Ingleside once it reaches Market Street. The T-Third line is regularly off schedule, according to a 2016 study by the city transit agency.

UCSF’s discussions with the task force are required as part of the real estate development process. The next meeting is slated for April 24.

If UCSF sticks to its schedule, the housing project will be finished by summer 2019 and the clinic by spring 2020. 777 Mariposa St. is still under its previous owner’s lease until 2018, the earliest that UCSF can assume ownership.