Last winter, the San Francisco Public Press published a detailed, data-rich narrative showing how private funds have saved a few schools from the ravages of years of budget cuts, but ended up exacerbating educational inequality within the San Francisco Unified School District.

As a researcher for the project, I assisted the team in scouring through mountains of public documents, including budgets, California Department of Education data reports, hundreds of parent-teacher association nonprofit tax returns and statistics from other state and local agencies.

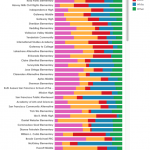

The data made clear that even with policies intended to level the playing field by giving more district allocations to struggling schools, educational equity within the district was far from a solved problem. PTA fundraising quadrupled during years of budget cuts, but 10 elementary schools raised almost as much money as the other 61 combined. This allowed them to blunt the effects of the cuts.

Many of our findings never made it into print but nonetheless helped provide important insights.

One question kept turning up: If PTA expenditures influence educational equity among schools within the district, then do they also have an effect on academic performance? More specifically, is there a statistically significant correlation between PTA program expenditures and a school’s Academic Performance Index?

While our story last year did not address this question head-on, we knew it was at the crux of our inquiry.

After we published the report, I analyzed the data more closely as a graduate student at San Francisco State University. The study examined 39 elementary schools in San Francisco Unified, including expenditures, achievement scores and student demographic data — enrollment, subsidized lunches, English language learners, the number of full-time teachers and base API test scores from 2009 to 2012.

My statistical regression analysis showed that, in fact, PTA program service expenditures, socioeconomic factors and district budget allocations all had a significant correlation with a school’s test scores. It’s important to not confuse correlation with causation, but correlation is very important. It reveals previously hidden relationships that might provide clues for why things are the way they are. In this case, the analysis shows that PTA fundraising is strongly associated with educational outcomes.

That finding is one piece of evidence that inequality persists within the schools, despite the district’s efforts to provide equal educational opportunities.

District-Level Funding

The study found that per-pupil budget allocations from the district had a negative correlation with a school’s API test score. This makes sense, because under the most recent reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, a school with lower academic achievement scores is provided additional federal financial assistance to increase performance. More funding does not lead to lower achievement — the chain of causation is the other way around.

The issue is particularly timely as Gov. Jerry Brown’s Local Control Funding Formula, which redistributes subsidies to districts with the most disadvantaged students, is taking effect across the state. But this law only loosely governs how funds are spent within school districts.

Even before the state law passed, San Francisco Unified relied on a weighted student funding formula to allocate resources to each school. The system works by first providing a base amount for each student enrolled. Additional funding is then provided for socioeconomically disadvantaged students enrolled in free or reduced-price lunch programs, special-education students and English language learners. Restricted funding is also provided for specific uses.

Once funding is allocated to the school, the principal and locally elected school site council determine specific budget allocations for academic programs and teachers.

Our findings show that PTA donations have a significant correlation to academic achievement despite the additional funds for disadvantaged schools. But here the direction of causation is not so clear. Do PTA activities bolster academic performance, or is an effective PTA just another manifestation of the advantages affluent families bring to the table? It could also be the case that academic achievement fosters greater PTA activity.

We cannot say for sure. At the very least, the study suggests that school administrators be mindful of the potential effect of PTAs on equity.

Responses to the Project

We know that our report triggered intense conversations among parents and educators. As public school parent Alex Wise wrote to lead writer Jeremy Adam Smith:

My wife, Moira, and I loved your article in the S.F. Public Press and it inspired us to think about solutions to PTA equity gap issues. We are formulating a PTA sister school idea that we think could help to address the current imbalance in PTA funding in San Francisco public schools.

We’ve spoken with SFUSD Commissioner Matt Haney as well as Masharika Maddison of Parents for Public Schools, and both of them were quite receptive to the concept. We passed along your S.F. Public Press report to both of them as well as your KQED appearance from Feb. 14 to help them recognize the problem.

The conversation continues. On Dec. 9, another public school parent, Annie Bauccio, wrote on her business blog:

In San Francisco there’s been a bright light shining on this issue of equity for years. Reporter and public school dad Jeremy Adam Smith published a special report on education inequality in the San Francisco Public Press earlier this year which garnered a lot of heated schoolyard discussion. I was among the heated: after serving as the fundraising chair at our little (failing) elementary school the PTA budget climbed from $12K annually to nearly $300K.

The overwhelming personal response I had to this success was guilt: how could I be doing for our school and allowing the school (the children!) down the block to fail? And so I turned to advocacy and political action as a way to combat spending cuts that have risen to $20 billion since 2008. California now has a statewide education advocacy organization called Educate Our State that I am proud to have cofounded.

We are heartened that our reporting has led officials to propose reforms to change the way public schools are funded based on our reporting.

We don’t pretend to have all the answers. As journalists and researchers, our main job is to reveal facts and patterns — and to raise questions.

Our project, which won the 2014 excellence in explanatory journalism award from the Northern California chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists, illustrates the need for more investigative and explanatory reporting that relies on both personal stories and a close look at the statistics to make sense of trends that are otherwise easy for policymakers to overlook.

This story was published in the winter 2015 print edition of the Public Press. For the full report rolling out online through early February, see sfpublicpress.org/schooldiversity. To read the 2014 report on the effects of parent fundraising and (follow-up coverage), see sfpublicpress.org/publicschools.