PUBLIC SCHOOLS, PRIVATE MONEY: Parent fundraising for elementary education in S.F. skyrocketed 800 percent in 10 years. The largesse saved some classroom programs, but widened the gap between rich and poor.

Part of a special report on education inequality in San Francisco. A version of this story ran in the winter 2014 print edition.

Evelyn Cheung is the principal of Junipero Serra Elementary School in Bernal Heights. Matthew Reedy is the principal of Grattan Elementary in the Haight. Both San Francisco public schools faced five straight years of districtwide budget cuts — which hit hardest in 2010 with a $113 million shortfall and last school year came to a more manageable $13 million.

But the belt tightening did not hurt the two schools equally. Cheung was forced to lay off staff and take other drastic steps, like freezing supply purchases for a year. By contrast, Reedy hired new staff and expanded his school’s academic programs, helping raise standardized test scores.

Why? The difference lay in the ability of their parent-teacher associations to raise money. The Grattan PTA has budgeted hundreds of thousands of dollars a year, amounting to almost $1,000 per pupil. At Junipero Serra, where most students come from poor and immigrant families, the PTA raises approximately $25 per pupil.

“Every principal knows which schools have it and which schools don’t,” Cheung said. “We know who are the haves and who are the have-nots. The system just isn’t equitable.”

In an era of shrinking public investment in schools, parents have struggled to hold the line one school at a time. Since the pre-recession year 2007, elementary school PTAs in San Francisco collectively managed to more than quadruple their spending on schools.

With this money, some schools have been able to pay teachers and staff, buy computers and school supplies, and underwrite class outings and enrichment activities. These expenses, previously covered by the taxpayers, are increasingly the responsibility of parents.

But school district finance data, PTA tax records and demographic profiles reveal an unintended byproduct of parents’ heroic efforts: The growing reliance on private dollars has widened inequities between the impoverished majority and the small number of schools where affluent parents cluster.

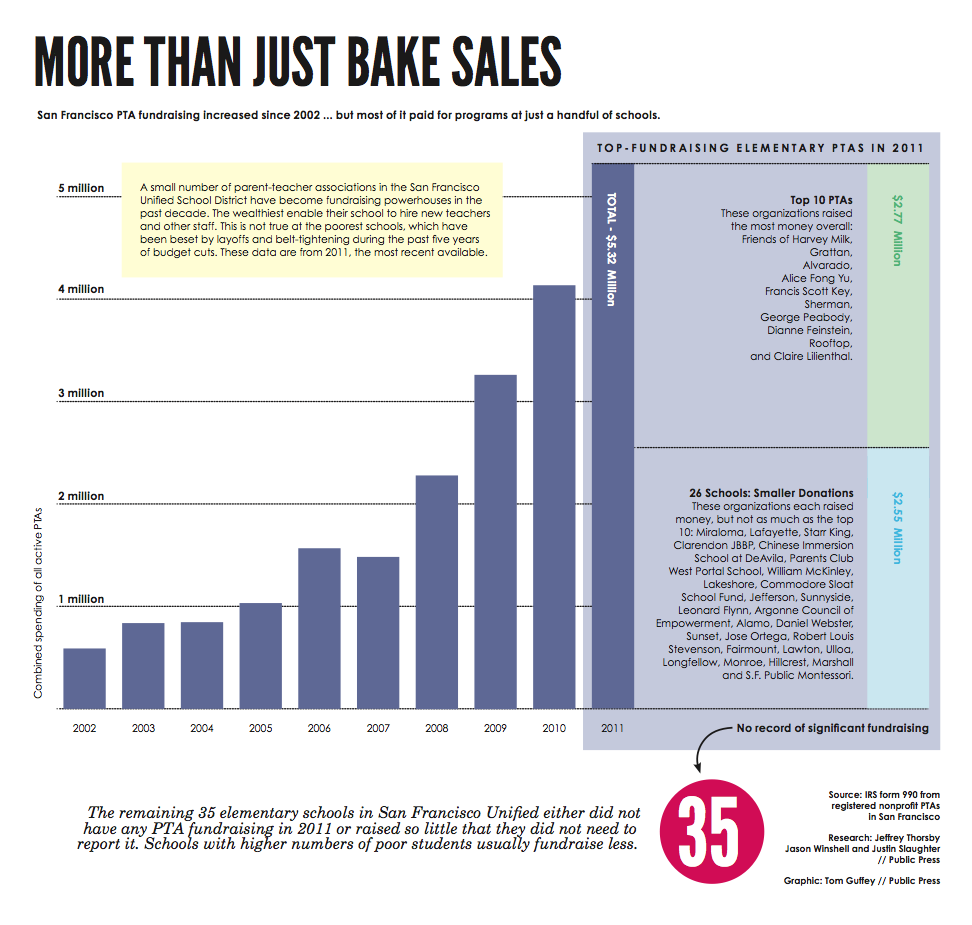

Unlike some California school districts, which centralize and redistribute funds raised by parents, San Francisco so far has permitted all money raised at a school to stay there. This gives some schools an enormous advantage. School district data show that in 2011 (the most recent year tax records were available), parents of children at just 10 elementary schools raised $2.77 million — more money than those at the other 61 combined.

By bringing in as much as $1,500 per student, the top fundraising schools appear to have been largely insulated from the effects of budgets cuts. Meanwhile, parents at high-poverty schools such as Junipero Serra are seeing shrinking resources for their children. This means laid-off staff, dilapidated libraries, outdated computers and a dearth of essential supplies like pencils and paper.

|

PDF preview |

Rachel Norton, president of the San Francisco Board of Education, said she and her colleagues were aware of significant disparities in the fundraising capacities of PTAs in the district. But administrators do not track donations, nor do they attempt to interfere with school fundraising.

“I’d never ding parents for raising money to provide more services and extras for their schools, especially in a state like California that has chronically underfunded schools,” Norton said. “The more economically diverse students the schools attract, the better off the schools will be.”

But fewer and fewer schools in San Francisco are attracting economically diverse students. The number of children from poor families is rising across the district, and there are more schools with high concentrations of poverty than there were 10 years ago. Meanwhile, the number of mixed-income schools is shrinking.

The district’s “lottery” system is supposed to keep schools racially and economically diverse by giving preference to students from disadvantaged backgrounds and neighborhoods when assigning spots. But data suggest it has largely failed at that task, perhaps since affluent parents have had the time and skills to game the system, and tend to cluster in certain schools.

Critics of rising income inequality say school districts across the country, in a rush to save public schools with private dollars, created a system in which education is improving for the affluent and declining for the poor.

“Parent fundraising has become more important as state and local funds have dwindled,” said Robert Reich, a former U.S. secretary of labor and now a political science professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who advocates for policies to close the gap between rich and poor.

“If we take the ideal of equal opportunity seriously,” Reich said, “we’ve got to commit ourselves to creating a system of public education in which kids from poor and working-class families have a genuinely equal opportunity to succeed. And we’re falling far short.”

In an effort to address unequal parent fundraising head-on, some Bay Area school districts have pioneered novel solutions that might be instructive to San Francisco. One is aggregating private dollars, and directing them to the schools that need the most help. Other California districts prohibit PTAs from paying for teacher salaries or training, a common practice that can significantly widen inequities among schools.

But with an expected influx of state money this year, San Francisco will have new policy options to address the growing inequities in the district. The city’s schools stand to bring in as much as $21.7 million more as soon as September, through Gov. Jerry Brown’s newly enacted Local Control Funding Formula, which provides extra funds to districts with many disadvantaged students. If student populations remain stable, this new money could grow to $184.6 million annually in eight years.

With a current school district budget $667 million, the new funds would represent an increase of 27 percent.

As San Francisco’s Board of Education prepares to hold public meetings this spring on how to spend the extra funds, the fate of increasingly unequal public schools could be in the hands of parents themselves. That may mean endorsing reforms to ensure more equitable local funding, or agreeing to share fundraising proceeds among schools.

SOME SCHOOLS DODGED CUTS

Matthew Reedy started working as a teacher at Grattan Elementary in the Haight in 2002. That was the year the district’s Weighted Student Formula took effect. The policy, devised as a way to help disadvantaged children, provides schools with a base rate of funding for each student, currently $2,896, and adds dollars based on need, such as the number of children receiving special education services, free and reduced-price lunches and lessons in English as a second language. So per-capita funding for schools is highly variable but generally biased toward schools with disadvantaged students.

The goal is not strict equality, but rather equity, meaning preferential funding for schools that need it most. San Francisco schools with many poor and immigrant students have bigger budgets on a per-pupil basis than do affluent schools, whose students are less expensive to educate.

When the formula went into effect in 2002, Reedy said, affluent schools such as Grattan lost funding, and parents felt compelled to make up the difference.

That year, elementary school PTAs in San Francisco brought in a total of just $592,000. But through 2011, their combined budgets had ballooned to $5.32 million, an increase of about 800 percent.

(The Public Press examined data from elementary schools only based on the tax records of legally recognized PTAs.)

As parent fundraising increased, so did the gap between the richest and poorest schools.

In 2010, Reedy became Grattan’s principal. Today, only 21 percent of 359 students there qualify for free and reduced-price lunch. That is one-third the district average, making it one of the wealthiest schools in a district whose students overall have gotten poorer. Not surprisingly, the Grattan PTA is one of the most successful fundraisers in the district.

In the 2012–2013 school year, the PTA at Grattan had a budget of $353,000, about $983 per pupil, on top of the base $2,896 the school receives from the district for each student. The parents rely on an array of labor-intensive fundraising methods: “Count Me In!” parties with ticket prices up to $75, wine raffles and auctions, foundation grants, “Dine Out for Grattan” nights at participating restaurants, and a sophisticated e-newsletter and website.

See Flickr for a photo essay on fundraising for public education by Tearsa Joy Hammock and Luke Thomas

Reedy said Grattan has been spared the sting of budget cuts, thanks entirely to these parent fundraising efforts. “We’ve been able to take PTA money and donate it to our general fund to prevent layoffs,” he said.

Not only did the PTA protect jobs, it expanded Grattan’s academic programs by hiring reading specialists and a technology teacher, and adding a bilingual clerk and a parent liaison to the staff. The PTA also funds an extra teacher, helping Grattan actually reduce its average class size. In all, this school year the Grattan PTA is paying all or part of the salaries of six staff, totaling nearly $224,000. PTA money also supported the library, a garden that doubles as a science lab and a computer lab that is often cited as one of Grattan’s key strengths, among other programs.

Like many principals, Reedy sets spending priorities in consultation with a school site council, which includes parents, teachers and neighbors. Their decision to invest PTA funds in academics has paid off. From 2008 to 2013, Grattan improved standardized test scores from 787 to 923 points on a scale of 1,000, making it one of the district’s academically best-performing elementary schools.

While the sums raised by Grattan’s PTA may seem tiny compared with a district budget of $667 million, Grattan’s example reveals how small — but concentrated — amounts of private money can keep an entire school afloat. For schools with the means, parent fundraising is a solution to budget cuts.

But our analysis finds that the majority of San Francisco schools are unable to raise money at the same level. Indeed, reliance on parent fundraising appears to undermine the equitability goal of the district’s own funding methods.

HOW CUTS CREATE INEQUITY

Junipero Serra Elementary is situated between Holly Courts, a low-income housing project, and the hilltop Holly Park in Bernal Heights. Visitors hear more Spanish than English in the school’s hallways — 90 percent of the 269 students are immigrants or the children of immigrants, mainly from Latin America.

As principal, Evelyn Cheung has had to make hard choices in the past five years, in consultation with teachers and parents. One year they stopped buying supplies. The budget for the library fell to $500. Cheung was forced to lay off classroom aides, the nurse, the social worker and all “consultancies” — mainly arts teachers. The layoffs hurt morale more than other cuts, Cheung said, “because it’s people.”

“They have emotional ties, and there are bad feelings when someone is laid off,” she said.

Why can’t Junipero Serra fundraise its way around budget cuts? In part, because the parents have less to give, at least as measured by free or reduced-price lunches. At Junipero Serra, 86 percent of students qualify, more than four times as many as at Grattan.

To qualify for reduced-price lunch in California, a family of four must make less than $42,643 a year. To qualify for free lunch, less than $29,965. Researchers use these markers as proxies to measure poverty.

But those incomes are more meager in San Francisco, which in the past two years has had the most expensive housing in the country, straining the ability of poor families to pay for basic necessities. In San Francisco, the average rent for a two-bedroom apartment is now $3,942 a month — a stunning rise of $1,000 since the start of 2013.

The desperate situation faced by most of Junipero Serra’s families is, in fact, shared by 63 percent of families throughout San Francisco’s public school system. This represents a 10 percent increase since the start of the recession, which coincided with the start of the budget cuts.

This poverty has also become more concentrated. Data from the district show that the number of schools in which more than three-quarters of students are eligible for subsidized lunch has more than tripled in the past decade. Schools in which fewer than one-quarter qualify increased slightly. Meanwhile, the middle class is disappearing: The portion of schools in between those extremes of poverty and wealth fell, from 66 percent to 52 percent.

While Cheung lauded the ideals behind the weighted student formula, and similar federal programs such as Title I, she said current funding levels were not enough for schools with large numbers of disadvantaged students.

“Many of my parents don’t have the resources that many middle-class families have,” Cheung said. “We have to provide a computer lab and technology training for the kids because they don’t have computers at home. And they will go to middle school very far behind if we don’t provide that support.”

The disadvantages do not stop with electronic devices. “Many of our Spanish-speaking families work two jobs,” Cheung said.

Inflexible schedules that often come with working-class jobs make it hard for parents to volunteer in the classroom, which might otherwise make up for the layoffs of classroom aides, or help kids stay on top of homework — assuming the immigrant parents can read assignments in English. Hectic schedules create barriers to getting involved in the PTA, hurting the school’s chances to raise money and buffer against shortfalls. (See print edition photo essay, “Two PTA Presidents, Two Realities.”)

“They care a lot and they’re involved, but not in the traditional ways,” Cheung said.

THE TWO SIDES OF FUNDRAISING

This is how budget cuts perpetuate inequity: Affluent families are able to make up for lost funding by donating both time and money, whereas schools with poor families struggle to fill the gap. School district data show that as the number of students getting free and reduced-price lunch rises, PTA budgets fall. At the 44 elementary schools where a majority of the students live in poverty, fundraising is insufficient to offset budget cuts. Those cuts add stress to communities already struggling with low wages, financial instability and discrimination.

Despite these challenges, Junipero Serra has improved its academic performance. It saw its standardized test scores rise by 36 points in the past two years, to 752. But that is still below what the state deems “adequate yearly progress” and almost 200 points behind Grattan.

Cheung attributes the modest gains to “superhuman” efforts by teaching staff, doing more with less. “It’s a waste of time to be frustrated,” she said. “We just need to build on the strengths that we have.”

For Cheung, the problem is not that other schools have more money — it is that the needs are so different.

After including PTA contributions, per-pupil expenditures for Grattan and Junipero Serra come to within a few hundred dollars of each other. But this equivalency is misleading. Under the district’s weighted student formula, Junipero Serra is supposed to receive more money than Grattan.

The “extra” money going to Junipero Serra through the funding formula is for basic necessities: subsidized lunches, special education, English-language instruction and computers, to which the kids have little access at home. So Cheung’s expenses are higher than Reedy’s, and parents are not as able to help in the classroom to make up for layoffs.

While the kids at Junipero Serra start life on first base, most of Grattan’s are already on third. It is not hard to see why education inequality, as Robert Reich describes it, persists. Grattan does not need to cope with the same chronic insecurities confronting Junipero Serra, where families struggle with the stresses of living on the financial edge both at school and in the home.

“We shouldn’t have to fight so hard to provide kids with a strong foundational education,” Chueng said.

PARENTS NOT TO BLAME

Alvarado Elementary in Noe Valley is, in a way, an exception to this trend toward inequity, and might represent the best-case scenario in a system that overall is rigged against poor students.

The school draws poor and working-class Latino students from the Mission, as well as affluent white and Asian families from Noe Valley and the Castro. As a result, it is more diverse than both impoverished schools like Junipero Serra and affluent schools like Grattan. Forty-two percent of Alvarado students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch.

Carl Bettag, a product designer and father of twin fourth-graders, leads fundraising efforts for Alvarado’s PTA, which this year aims to raise $375,000, or about $721 per pupil. That is considerably more than Junipero Serra, but less than Grattan.

With this money, the Alvarado PTA has staved off layoffs, supported literacy programs and launched and maintained a regionally famous arts program. It has initiated environmental programs, such as solar panels, that also provide learning opportunities.

Bettag said the low-income students at Alvarado benefit most from the fundraising prowess of middle-class families in an income-diverse school.

“If you were to walk into Alvarado, you would find a vibrant, functional school, but you would not find a gold-plated school,” he said. “The science room does not have a sink! Some of the computers don’t work. Alvarado needs all the money and support it’s getting. We have 500 students at the school. It’s the 200 students who are on free and reduced lunch that benefit most from all the effort and money that goes into the school.”

Bettag said he could not ask parents at Alvarado to contribute for other schools, and he was not sure that he should.

“The fundamental problem is that the public schools are woefully underfinanced, and nothing that the PTAs do is going to fix that problem,” he said. “The real problem is not at the local level. It’s at the state level.”

Reich agrees. After serving as secretary of labor in the Clinton administration, he has campaigned against economic inequality through books, articles, speeches, TV appearances and most recently the film “Inequality for All.”

“Parents should not be blamed for school inequality,” Reich said. “They should be thanked for making donations to their children’s schools. The problem is not with them. The problem lies much deeper. The problem is that we have a system of school finance that is topsy-turvy. Poor kids tend to end up in the worst schools, with minimal facilities, when they should be getting the best we as a society can offer.”

Unlike School Board President Norton, Reich said he does not believe that a hands-off approach is best for tax-deductible parent donations. Donations by parents to their children’s schools are not charity, Reich argued. It is the opposite — helping one’s own offspring instead of the less fortunate. These tax deductions diminish government revenues that could have gone to rich and poor schools alike.

NO EASY SOLUTIONS

Can the system be improved, or are we doomed to perpetuate the cycle of inequality? This problem is not unique to San Francisco. As anti-tax sentiment in recent years has reduced school funding nationwide, parents are increasingly fundraising to keep their own kids’ schools afloat.

In response, some California districts created centralized PTA foundations to redistribute funds to schools based on need (see story on the solution used in the East Bay city of Albany). Others prohibited PTAs from raising funds for personnel or professional development.

The Santa Monica-Malibu school district embraced both solutions in 2011, under Superintendent Sandra Lyon. Today the district’s education foundation is the only way parents can donate money to support teachers and staff.

The key worry about such systems is that they will reduce the incentive for parents to support public schools beyond what they already pay in taxes. Lyon said her district struggled with the transition: “There are still some who believe parent money should stay at their children’s schools, and they are strongly against the change.”

The reform caused some affluent Malibu residents to try to break off from more working-class Santa Monica to create a separate school district. At least one Malibu school refused to participate in revenue sharing.

Overall, the district’s PTAs are struggling to raise as much as in previous years, Lyon said. Still, she sees progress. The foundation launched a $4 million campaign last spring, and by late fall 2013 it had raised $2.4 million.

“Some of our wealthiest Santa Monica schools have the greatest participation,” Lyon said. “Indeed, across Santa Monica schools, some of the loudest opponents have become the biggest champions and are leading the charges at their schools.”

Lyon has seen a culture change in a district heavily divided by social class. “Schools are collaborating in ways they had not done before,” she said. “The inequity in schools had bothered many for years, and so there has been support for the notion that we are working to create a better education for all students.”

The Santa Monica-Malibu district is one-fifth the size of San Francisco Unified. Every education leader interviewed dismissed the idea that such a system would work in San Francisco, largely because of the district’s size and diversity. Most defended the status quo.

If San Francisco moved to such a system, Carl Bettag said, “I think you’d get a lot of parents pulling their kids out of public schools and putting them in private schools. I’d pull my kids.”

Many educators fear losing support from affluent parents, who have the option to quit the public schools altogether and enroll their children in private schools — or flee to suburban schools. Harvey Milk Elementary principal Tracy Peoples said fundraising can create that kind of parental engagement.

“For schools like ours that do not qualify for additional funding based on test scores or student demographics, we depend on the parent community to step in to help raise additional funds for our students,” Peoples said.

Because the San Francisco Unified School District does not keep track of donations to PTAs, parents and educators have not had an accurate picture of how they factor into inequities among individual schools.

But as California moves this year to pour millions of dollars into diverse, high-poverty districts like San Francisco, parents and educators must ask themselves hard questions about which students were hurt most by five years of budgets cuts — and who was rescued by PTA fundraising.

Some parents have led a grassroots movement to counteract the inequities. Alvarado parent Todd David worked with peers in 2008 to launch EdMatch, a Web-based volunteer effort to enlist corporations and philanthropists to match funds raised for San Francisco public schools. The money was distributed to the most impoverished.

“EdMatch is a good system,” board president Rachel Norton said, “because it encourages people to voluntarily opt in, without penalizing parents who are working really hard.” But EdMatch, while noble in intent, has struggled more than five years to increase participation, raising only $100,000 last year — well short of its $6 million goal.

FROM CHARITY TO ADVOCACY

The most effective solutions may be political, not charitable.

Reich counsels parents troubled by growing public-school inequities to turn their energies from giving to advocating for reform. He said they should work to raise tax rates for the wealthy, decouple school budgets from property taxes and target state and local resources to the poorest schools.

In a Sept. 4 op-ed for The New York Times, Stanford political science professor Rob Reich (no relation to the coincidentally named Robert Reich) went a step further, proposing that the federal government create a special charitable status for school-based PTAs, so that those who give to poor schools get double deductions and those who give to affluent schools get none.

Norton said the changes in state funding have sparked other possible reform ideas specific to San Francisco.

“We desperately need to reweight the student formula,” she said. This may be the most decisive battle to be waged in the next year on behalf of poor and immigrant schools such as Junipero Serra.

“A well-educated populace is the key to a healthy democracy,” said David, the Alvarado parent, who turned to full-time education activism after a successful Wall Street career. “Public education is an investment, not an expenditure. My grandparents were immigrants. They came to the United States, they got a public education, they lived the American dream. Education is the one way we know that can help each person rise, generation after generation. If you care about the future of America, education for all kids is in all our interests.”

Jeremy Adam Smith is a fellow with the Institute for Justice and Journalism. He edits the website of U.C. Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center and is author or coeditor of four books, including “The Daddy Shift,” “Rad Dad” and “The Compassionate Instinct.” His son briefly attended both Junipero Serra and Grattan.

Part of a special report on education inequality in San Francisco. A version of this story ran in the winter 2014 print edition. Buy a copy of the winter 2014 print edition through the website, or consider becoming a member and get every edition for the next year.

CLARIFICATIONS

• 2/6/14: The PTA at Grattan Elementary had a $353,000 budget, not income, in 2012–13. Parents there also noted that the after-school enrichment program was reported to the IRS as part of the PTA budget.

• 2/14/14: Grattan’s budget of $1,000 per student was not equal to the amount raised.