Local salespeople fail to disclose composite nature of gems

It was fall 2008 and the holiday sales rush loomed, Cortney Balzan recalled. That’s when he said he felt forced to confront one of America’s largest retailers and warn it that it might be misleading its customers.

For a quarter century, Balzan, an independent gemologist, had been responsible for the quality oversight, appraisal and repair of the precious gemstones that Macy’s West, the San Francisco based West Coast division of Macy’s, sold in its stores.

But beginning in 2007 and continuing throughout 2008, Balzan discovered that gems arriving for distribution and sale did not satisfy Macy’s quality standards. Topping his list of complaints were the rubies, which Balzan determined were composites of ruby and leaded glass worth an estimated $15 a carat.

The inferior ruby product, which began flooding the market around 2004, generated an industrywide debate about how vendors should market it. By 2007, a consortium of international gemological laboratories concluded that the new stones should be called “ruby-glass composites.”

In fact, the Jewelers Vigilance Committee, a leading industry watchdog, concluded that the stones could not be sold as “rubies” or “precious gems” under Federal Trade Commission guidelines, since they lacked the durability and value of bona fide rubies.

Balzan insisted that Macy’s West apply industry standards. But he said company officials ignored his recommendations to reject the goods or disclose their true nature to customers. As Christmas approached, he spent many late nights composing e-mails to Macy’s jewelry and legal executives in San Francisco and New York. “I told them that Macy’s had a problem,” Balzan said. “But all they wanted to talk about was how they could glamorize the product.”

In May 2009, Macy’s canceled Balzan’s contract for quality control and appraisal, but retained him for repairs. He continued to see the same substandard gems arrive at his laboratory, he said. Last December, Macy’s severed all ties with Balzan. He sued Macy’s that same month in San Francisco Superior Court, alleging that the store had contracted with him in bad faith.

The San Francisco Public Press conducted its own, independent investigation of Macy’s gems, which substantiated Balzan’s claims. This investigation found that Macy’s salespeople at all three of its San Francisco-area locations did not accurately describe its products and sold lead-glass-ruby composites as bona fide rubies, without disclosing their true nature.

In the past year, Macy’s gemstones have garnered some media scrutiny, though none in the general-circulation press. Two televised sting operations, one by “Good Morning America” last November and another by San Francisco’s CBS5 in February, supported Balzan’s allegations. In both shows, reporters purchased gems at Macy’s stores that were sold as natural rubies but found under testing to be composites.

In January, a former employee of both Macy’s and Balzan’s laboratory initiated a separate classaction lawsuit, also in San Francisco Superior Court, on behalf of customers who claim they purchased gems that were not what Macy’s represented them to be.

Despite the two lawsuits and media attention, Macy’s continued to sell the same controversial stones. In February, the retailer posted on its website a menu detailing gem treatment and proper care, with the rubies’ glass treatment and several other disclosures Balzan said he demanded. Macy’s stores maintain a similar chart behind sales counters to aid employees and customers.

But on separate visits two months ago to three Macy’s locations, salespeople did not make the charts available to a reporter who bought ruby jewelry. Macy’s staff also did not fully disclose the treatment and care of its gems when asked. Federal Trade Commission guidelines require such disclosures without prompting, prior to purchase.

A spokesman for Macy’s declined repeated requests for comment, saying the company does not discuss matters currently under litigation, and that a key staff member needed to answer questions was on vacation.

Macy’s offered the following written statement to CBS5’s February broadcast: "Ruby gemstones sold in settings in Macy’s Fine Jewelry departments are genuine. In general, rubies are heat treated to enhance their quality and appearance. Rubies also may be fracture-filled with glass or a glass-like substance during the heating process to improve the overall quality of the stone. We have signs in our precious and semi-precious gemstone departments to inform customers that gemstones may have been treated and may require special care. We are always available to discuss the quality of a purchased item with our customers because we want our customers to be satisfied. Rubies sold at Macy’s represent an outstanding value for our customers."

Though the laws on disclosure are clear, federal and state agencies have not publicly reacted to news reports or the lawsuits. To date, no regulatory agency — the Federal Trade Commission, the California Department of Consumer Affairs or the California Attorney General’s Office — has taken action against Macy’s.

LOCAL QUALITY CONTROL

In the mid 1980s, Macy’s West had problems in its fine-jewelry department, Balzan recalled. Some cubic zirconia were sold as diamonds. The company hired Balzan, who in 1983 had become the first master gemologist appraiser in northern California, as an independent contractor to improve its quality-control standards.

Balzan played an important part in Macy’s West’s elaborate system of checks and balances to ensure that everyone in jewelry sales knew what was being sold and how it had to be advertised. After Macy’s staff buyers purchased jewelry from vendors, the products arrived at the Macy’s Fine Jewelry Center on O’Farrell Street for distribution to the company’s 259 stores in the western United States, Hawaii and Guam.

Balzan and his team of checkers would then examine the merchandise to ensure that it met Macy’s criteria and satisfied the buyer’s request.

“We were the independent laboratory,” Balzan said. “Our goal was to give an objective, unbiased assessment, based on their standards.”

His analyses included identifying the type of stone, its quality, treatments and measurements. Balzan would even occasionally track down the mine the stone allegedly came from. “In quality control, you have to have some rejections, because no one is perfect,” Balzan said.

Gems that clearly didn’t meet Macy’s standards were stamped “RTV” — return to vendor. If the product’s quality was ambiguous, Balzan informed the Macy’s buyer, as well as jewelry executives and legal counsel, what the stone was and how it had to be sold to customers and advertised to the public. The buyer would then decide whether it was worth selling in Macy’s stores.

The Fine Jewelry Center was run by Mimi Lowe, whom associates nicknamed “Dragon Lady” for her strict adherence to the rules.

“I made sure everyone followed the standard,” said Lowe, who retired from Macy’s in 2004. “If there was a problem, you would bring in a partner, the upper echelon, legal, and you would make a determination.”

To ensure that Macy’s complied with federal and state laws, Balzan also helped develop detailed charts, explaining the treatment that each type of stone had received and the special care each required. These charts were supposed to be made available to customers, said Balzan, who also helped with the training of salespeople about proper disclosure.

Over the years, Macy’s took an increasingly larger share of Balzan’s attention. His staff grew to 18 people, who worked in the additional laboratory space that Macy’s provided in the Fine Jewelry Center. Balzan hired Lowe, its former director, as a consultant in 2006.

At the height of his relationship with Macy’s, the company represented 90 percent of Balzan’s business. Balzan’s lab was expected to be on call at all times to inspect shipments, especially before the holidays.

HODGEPODGE OF QUESTIONABLE STONES

Starting in 2007 and increasingly in 2008, gemstones began arriving at the Fine Jewelry Center that, according to Balzan and Lowe, not only failed to meet Macy’s quality standards but were not even the gems that vendors reported them to be.

There were sapphires whose fractures were filled with glass; “green amethysts” that were really praseolite (a form of quartz); “natural black diamonds” that were irradiated to induce color or that were really black sapphires; diamonds that were enhanced with laser drilling or were fracture-filled; and then there were the lead-glass-ruby composites.

In many cases, Balzan ordered the stones to be returned to the vendor. Most of the problem gems, Balzan and Lowe said, came from one East Coast company, BH Multi. Headquartered off Fifth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, BH Multi began as a small jewelry operation in Aruba founded by Fatollah “Effy” Hematian, an electrical engineer who emigrated from Iran in 1978 and became a jewelry designer.

BH Multi is now a top jewelry vendor for Macy’s Inc., which owns all Macy’s and Bloomingdale’s stores. Hematian also sells his Effy Collection merchandise on his own website and in stores throughout the Caribbean, in Alaska and in New York.

Despite the problems Balzan alleged in BH Multi’s products for Macy’s, the vendor gained an increasing share and superior location in the stores’ gem showcases, according to Balzan and Lowe. Today, Effy Collection jewelry, marked by black jaguar tags with gold “EFFY” letters, dominates the ruby, emerald, sapphire, and black diamond sections of the colored-gem area.

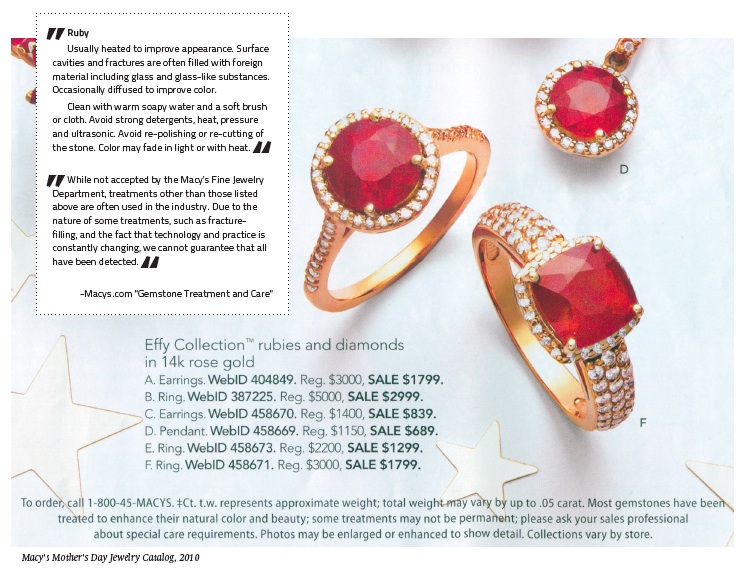

Effy Collection merchandise occupied five pages of Macy’s 20-page jewelry catalogue for Mother’s Day this year. Vendors pay between $30,000 and $75,000 for each page that advertises their lines by name, according to a former Macy’s jewelry employee who requested anonymity to protect her current business relationships. The payments, she said, help defray the cost of printing and mailing. Vendors who pay for advertising receive preferential treatment, the employee said, because Macy’s jewelry buyers themselves have to solicit it.

BH Multi enjoyed a special status at Macy’s, Balzan and Lowe charge. Lowe’s successor as the Fine Jewelry Center’s director ordered Balzan to review fewer and fewer of the gemstones arriving from BH Multi. Nevertheless, Balzan still discovered the same problems, he said.

Benny Hematian, president of BH Multi and son of founder Effy Hematian, did not respond to repeated requests for comment, both by phone and e-mail. But a spokesman for the company, reached last week, said he was “almost 100 percent sure” that Macy’s “knew everything, and we disclosed every information that there is to disclose.” Without leaving his name, the spokesman directed this reporter to a company lawyer, who did not respond to questions e-mailed to him.

Balzan concluded that his quality-control laboratory was being bypassed when he noticed that gems that Macy’s sent to his lab for repair or resizing were the same ones he had rejected. Such repair or resizing requests normally came from customers who had purchased the jewelry at Macy’s. The retailer, Balzan believed, was ignoring his guidance.

This differed from Balzan’s experience of working with Lowe when she was the Fine Jewelry Center’s director. “We used to go back and forth,” Balzan said. “Under the new director, we didn’t have that same rapport.”

Such bypassing of quality control in jewelry distribution would constitute a break with prior practice, according to the unnamed former Macy’s jewelry employee. “We would never have gotten away with just bringing in any jewelry and sending it out there without knowing what we were selling our customers,” she said. “I mean, that never happened. Ever.”

In the run-up to the Christmas season in 2008, Balzan said he confronted the top Macy’s jewelry executives, both in person and by e-mail. He warned them that if any of the stones were sold in stores, Macy’s had the duty, under Federal Trade Commission guidelines, to disclose their true nature to customers prior to sale.

Robin Spector, a commission lawyer, said the sale of composite rubies places a burden of disclosure on the retailer or vendor, since any treatment that changes the value, permanence and care of a gem needs to be disclosed.

“The customer shouldn’t have to ask,” Spector said. “It should be disclosed so that the customer knows what he’s buying.”

But Macy’s jewelry heads didn’t share Balzan’s concern, Lowe said. She participated in the discussions and was told that vendor contracts cleared Macy’s of any potential legal responsibility.

Balzan rejected Macy’s legal view.

“You can’t always say the vendor is wrong,” Balzan said. “If they’re selling you material, and you have an independent gemology laboratory telling you it’s something different, you say, ‘We’ll check into it.’ And that’s what was always done at Macy’s.”

In spring 2009, Macy’s Inc. laid off almost all of its 1,400 San Francisco corporate employees and dissolved Macy’s West as a separate division (though employees were allowed to reapply for jobs with the firm). In May, the company ended Balzan’s quality-control contract. Balzan, in turn, was forced to lay off staff, including Lowe in August.

In December, idled by the additional loss of his Macy’s repair contract, Balzan hired Robert Tobin, a Bay Area attorney known for his prosecution of a priest sexual-abuse scandal at San Jose’s St. Martin of Tours.

“There were e-mails to everyone who was in charge,” Tobin said about Balzan’s suit. “Everyone was advised of the problem.” Tobin said he could not share the e-mails with the Public Press, due to the early stage of the lawsuit.

Last year in July and December, Lowe said she purchased ruby jewelry at Macy’s stores in San Rafael and Hawaii as gifts for relatives. She said she tested the rubies and they turned out to be composites. In January, she initiated a classaction lawsuit on behalf of customers who had purchased Macy’s gems.

“It will be demonstrated that Macy’s defrauded knowingly thousands and thousands of people,” said Thomas Brandi, the plaintiff’s attorney. “It’s a sad day when a name that could be trusted can no longer be trusted.”

Richard Marcus, a professor at Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco, said he thought there might be a hurdle getting a group of people such as the one in Lowe’s suit certified by a court as a class, because the lead plaintiff is a former insider.

WHAT WE FOUND

To test Balzan’s and Lowe’s claims, the San Francisco Public Press conducted its own independent investigation. On April 28, the newspaper purchased three Effy Collection ruby jewelry pieces (two rings and one pendant) at three separate Macy’s stores: in Union Square, in the Stonestown Galleria and in Daly City’s Serramonte Center.

The Macy’s listed retail price for the items totaled $6,400. The jewelry was actually purchased at a steep discount. Thanks to the Macy’s Friends and Family sale and after opening a new Macy’s account, this reporter bought the items for $2,821, including sales tax.

In each store, the jewelry cases had index-card-sized signs stating that gemstones may have been treated, and that customers should ask staff for more information. Before each purchase, the reporter asked the salesperson to explain the treatment each ruby may have received. Each employee acknowledged that the rubies may have been heated, a commonly accepted practice that permanently improves color and clarity.

None mentioned the possibility that the rubies may have had fractures filled with glass (as acknowledged by Macy’s gem treatment chart linked from the company’s website) or were glass-ruby composites.

But Macy’s staff did not simply neglect to share the fine print with the customer.

The salespeople, after acknowledging the heat treatment, asserted that the rubies were “natural,” “a real ruby,” “not synthetic” and “not a lab ruby.”

None mentioned that the rubies required special care or that their redness can fade over time, especially in light or heat. Only one salesperson suggested that it should be cleaned with warm water. Yet according to the website, ruby purchasers must “clean with warm soapy water and a soft brush or cloth,” “avoid strong detergents, heat, pressure,” and “re-polishing or recutting of the stone.”

Each piece of jewelry was accompanied by a tag, “Fine Precious Ruby,” with no other caveats or explanations.

The Public Press then sent the jewelry to New York’s American Gemological Laboratories, one of the nation’s most respected, for testing. Christopher Smith, its president, concluded that all three stones were composite rubies that were "heavily treated using … lead-glass to fill fractures and cavities."

It was impossible to determine exactly how much glass the gems contained without destroying them, Smith said.

The newspaper also examined the stones for lead content — an additive used to improve the visual properties of the glass. The test was conducted with a Thermo Fisher Scientific XRF Analyzer, commonly used to check for traces of the metal in consumer products. All three pieces showed significant lead content.

Local accredited gemologist and appraiser David Harris examined the three stones, which weighed between 1.4 and 2.8 carats. He valued them at approximately $40 per carat.

In May, the reporter returned the jewelry to the three stores and alerted its salespeople, who weren’t the same ones who sold the merchandise, that the rubies were determined to be composites of ruby and leaded glass. The first salesperson twice repeated that “they do that to prevent it from cracking.” The second appeared shocked and disputed the gemologist’s report, claiming that it was “definitely ruby.” When told that the only disclosure made before sale concerned heat treatment, she said that heating is common — then also acknowledged a possible further treatment.

“We’ve been told that sometimes, if there’s a crack in the stone, it’s filled,” she said. “But it’s definitely a natural ruby.”

The third salesperson replied that it was “no secret” that Macy’s sells rubies with glass. She then placed on the counter the Macy’s gem treatment and care chart, encased in a plastic stand, that previously had been out of view of customers.

CHEAP AND BRITTLE

Almost all gems sold nowadays are treated in various ways to enhance their beauty. Although such treatments present challenges for identification and disclosure, few have generated the controversies that the lead-glass fill of rubies has.

“I think it’s the most serious issue that the jewelry industry has ever faced,” said Antoinette Matlins, an internationally recognized gemologist with seven books in print.

For more than 25 years, leaded glass has been used to fill fissures in raw corundum — the species of stone that includes ruby and sapphire — to enhance their clarity and color before being faceted. But around 2004, gemologists started seeing a new, more radical form of glass fracture-filling in rubies. Finished stones showed numerous bubbles under microscope, indicating that an increasing amount of glass was being used. In some stones, the glass was acting as an adhesive, holding the underlying bits of corundum together. Gemologists found that after melting away the glass additive, some rubies were shown to be at least half glass.

“Rubies are on the forefront because of all the foreign material,” Harris said. “It changes the whole characteristic of the stone.”

Natural ruby is the second hardest stone in existence, behind diamond. Composite rubies, however, are fragile and require special care. They can crack and lose their color over time. If exposed to everyday household products like strong detergent or lemon juice, the glass can quickly degrade. Only the lightest of cleaning treatments should be applied.

Thanks to their fragility and foreign additives, glass-lead-ruby composites are worth a fraction of the value of real rubies. Rubies of similar, lesser clarity and color cost $350 per carat wholesale, while high-quality natural rubies run $5,000 to $12,000 per carat. Ruby composites, by contrast, are worth $1 – $50 per carat.

The quality and value of composite rubies are so inferior, Matlins recommends an entirely different name — “rubaire.”

“It’s ruby with a lot of air, filled with glass,” she said. “Call it whatever you want, and charge $10 or $20 for it in the costume-jewelry aisle.”

Composite rubies are also difficult to detect with the naked eye. That, combined with their fragility, makes them especially problematic for gemologists and jewelry salespeople. Several gemologists interviewed mentioned stories of bench jewelers placing composite rubies in gem cleaning solutions, having them dissolve like Pop Rocks, and then being blamed by their owners for the damage.

The sale of precious gemstones, a $28 billion market for U.S. jewelry stores, is governed by state and federal laws intended to ensure that customers know what they are buying. As gem technology has advanced, so too has the challenge in properly identifying gems and the obligation to share that information with customers.

According to Federal Trade Commission standards, it is “unfair or deceptive” to call a gemstone by its name if it “is not in fact a natural stone” or if it is “manufactured or produced artificially.” Stones should not be called “gems” or “rubies” if they don’t possess the “beauty, symmetry, rarity and value necessary” to qualify as such.

INDUSTRY SELF-REFLECTION

On this basis, Suzan Flamm, a lawyer for the Jewelers Vigilance Committee, has concluded that composite rubies cannot legally be called “rubies” or “gems” without qualification. “You’re not talking about a ruby or anything natural,” she said. “It’s disturbing to those of us who care a lot about integrity and not getting over on consumers.”

Flamm has joined other industry experts calling for reforms of the nomenclature and disclosure of ruby composites. Earlier this month during the JCK Las Vegas jewelry convention, Matlins emceed a seminar with Flamm and other speakers on composite rubies, sponsored by the American Gemological Association. The session was one of several at such conferences in the past three years.

“I’m very much concerned with the issue of proper representations and proper disclosures,” said Smith of the American Gemological Laboratories, who spoke at the session. He called Macy’s a high-profile example of a general problem in the industry.

“We don’t know how much of the material has been sold to consumers,” he said. “Since we don’t know how much has been sold, we don’t know how much has been properly disclosed.”

Matlins was more vehement in her criticism of Macy’s and the consequences for the industry.

“I really think Macy’s should be nailed to the wall for this,” said Matlins, who visited a Macy’s in Tucson last February and used her loupe to identify ruby composites in the retailer’s jewelry case. “They should have taken them out of the store, but they haven’t, and they’re still charging exorbitant prices.”

Despite its nationwide presence, Macy’s has always retained a special status in the hearts of San Franciscans. Since 1866, its flagship store has anchored Union Square as a treasured city landmark.

That history was lost, Balzan and Lowe said, after last year’s mass layoff and the dissolution of Macy’s West. They see the quality-control standards that they upheld as part of the unique Macy’s West culture that made it a superior franchise.

“I don’t want to talk about Macy’s nowadays,” Balzan said. “I get angry and my blood pressure rises.”

In his spare time, Balzan teaches gemology. He occasionally takes his students to Macy’s and other stores around town to test their wares.

He still maintains his laboratory on Market Street, a block away from Macy’s, with a staff of four. His employees include his son Patrick, who is also an accredited gemologist.

“I’m disappointed in the way everything ended up,” the younger Balzan said. “We put a lot of work into Macy’s.”

A version of this article was published in the summer 2010 pilot edition of the San Francisco Public Press newspaper. Read select stories online, or buy a copy.