The Bay Area Toll Authority passes on the cost of mounting bond debt by raising tolls again and again //

In the alphabet soup of government agencies responsible for the region’s bridges, one body stands out for its unique, far-reaching powers of the purse—the Bay Area Toll Authority.

BATA is the financial lynchpin of what amounts to a multimillion-dollar business charging motorists to cross bridges. Like much of the bureaucratic infrastructure surrounding toll bridge operations, BATA is a creature of the state Legislature, formed by politicians in 1997 to pay for their expensive promises to motorists.

BATA’s primary responsibility is funding the Bay Bridge east-span replacement and other massive seismic-retrofitting programs. Since 2005, lawmakers have greatly expanded the agency’s role as the rich uncle to Caltrans, which owns and operates seven of the Bay Area’s eight toll bridges—the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge, the Antioch Bridge, the Benicia-Martinez Bridge, the Carquinez Bridge, the Dumbarton Bridge, the Richmond–San Rafael Bridge, and the San Mateo Bridge. BATA also provides substantial funding for the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, the lead planning agency that has its fingers in almost every mode of transportation within the nine counties that make up the Bay Area. Previously, tolls could only be increased with approval of the Legislature; now, the agency can raise them at will.

Another dollar for safety

BATA has wasted no time in utilizing its new authority; it intends to raise tolls on all seven bridges by at least $1 on July 1, 2010, bringing the basic charge—the amount paid by passenger vehicles—to $5. The $1 increase will be the third seismic surcharge in twelve years. In 1989, at the time of the Loma Prieta quake, the toll was $1. In 1998, the first $1 seismic surcharge was imposed, followed by a $1 increase in 2004 mandated by passage of Regional Measure 2, which authorized raising the toll on all bridges. A second $1 seismic surcharge was imposed in 2007, bringing the total to $4. (These increases do not affect the Golden Gate Bridge, which is managed by a separate entity.) Over the past eight years, tolls extracted from Bay Area commuters and other motorists have totaled some $2.3 billion, with nearly a third of that, $792 million, generated at the Bay Bridge toll plaza.

Since 2007, nearly half of that toll revenue has been earmarked for seismic retrofit and replacement projects. The rest is used to reimburse Caltrans for operating and maintaining the toll bridges, or is funneled through the Metropolitan Transportation Commission to other transit agencies, including San Francisco’s Muni, BART, AC Transit, and the South Bay’s Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority, and to other projects mandated by voter-approved ballot measures.

This steady stream of toll collections is also used by BATA as collateral for billions of dollars in revenue bonds issued to finance construction of the Bay Bridge east span and seismic-upgrade work on other bridges. More than $9.1 billion has been borrowed since 2001. Of this amount, BATA has directly borrowed $6.9 billion through its own bond issues. (The balance was generated through bond issues by other entities.)

CHIP IN FOR THIS REPORT ON SPOT.US |

With refinancing of some outstanding bonds and debt payments on others, as of last month the total outstanding principal balance on BATA-related debt was $5.6 billion, including $1.3 billion borrowed in November. But this year’s borrowing is hardly the end of the road. BATA anticipates borrowing as much as $1.5 billion more by 2012, and additional borrowing beyond that figure may be needed.

This growing level of debt will almost certainly prompt future toll increases beyond next year’s planned surcharge. BATA is even considering the possibility of congestion pricing on the Bay Bridge to maximize revenue.

The borrowing binge

It is BATA’s ability to unilaterally raise tolls in support of its continued borrowing that makes the agency particularly attractive to Wall Street—BATA is anything but a subprime borrower. In November, Standard & Poor’s, one of the nation’s three largest rating agencies, gave BATA’s bond issue its second-highest investment-grade rating, justifying its decision by pointing out that BATA had “no limits” when it came to raising tolls to repay debt—and “no requirement of legislative approval.”

Although BATA itself has borrowed the lion’s share of all money raised for California toll-bridge seismic retrofitting and replacement projects, as well as for other voter-mandated undertakings, its role as prime borrower didn’t emerge until 2005. It was then that state lawmakers, unhappy with Caltrans missteps in managing costs for Bay Area bridge work, gave BATA primary responsibility for bankrolling the ambitious toll bridge retrofitting program.

Of the $2.2 billion borrowed during the initial phase of retrofit work between 2001 and 2004—focused on retrofitting the west span, constructing a new west approach, and retrofitting other bridges—BATA’s borrowings totaled just $987 million. Most of the money borrowed for these early projects came from a bond issue by the California Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank, one of myriad state and local agencies created for the sole purpose of borrowing money without having the debt reflected on California’s financial statements, something that would adversely impact the state’s credit rating. In 2003 the Infrastructure Bank sold $1.2 billion in bonds and loaned $1 billion of the proceeds to Caltrans, which used $765.6 million to pay for the Bay Bridge west span retrofit and construction of the new west approach.

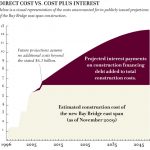

It wasn’t until Caltrans started awarding construction contracts for replacing the east span in April 2006 that BATA embarked on a borrowing binge. Coupled with the earlier borrowing, the current projected debt service—the principal and interest payments on all bonds outstanding to fund the entire Bay Area seismic retrofitting program, including the Bay Bridge—now exceeds $13.6 billion, saddling motorists with principal and interest payments for the next forty years. BATA projects that of this amount, interest payments alone will be nearly $8 billion by 2049. And that figure doesn’t include the $697 million in interest already paid.

Investment bankers cash in

BATA has managed to meet contractor paydays by performing an intricate financial ballet choreographed by Brian Mayhew, the agency’s chief financial officer. Mayhew plays all the angles to keep interest rates low, protects investors to maintain BATA’s high credit ratings, and hedges some of its bets using complex financial derivatives.

Not all of the money that BATA has borrowed has gone to construction. Millions of dollars have gone into the pockets of Wall Street investment bankers, lawyers, and financial consultants who put the deals together. Since 2006, BATA has paid at least $122 million in fees and other costs associated with issuing bonds. According to BATA records, between 2007 and last August, $75.7 million in fees were paid to two dozen firms, for a variety of services ranging from financial and legal advice to sales of bonds to investors. The largest recipient was Wall Street powerhouse JPMorgan Chase, which collected $50.5 million. Like closing costs on a conventional home mortgage, many of these fees are included in the amount upon which interest is paid.

//At least $122 million has gone into the pockets of Wall Street investment bankers, lawyers, and financial consultants who put the deals together.//

Although BATA is the primary borrower, there has been one departure from its standard practice of borrowing money directly. In December 2006, when additional funds were needed, BATA and its parent, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, raised the extra cash by creating the Bay Area Infrastructure Financing Authority (BAIFA) — a Joint Powers Authority which allowed the two public agencies to operate collectively. This new entity was used to obtain $888 million in what amounted to a “cash advance” from Wall Street, a loan that was secured by $1.3 billion in future toll-bridge project payments the state Legislature promised to make between 2006 and 2014. (The BAIFA structure was necessary to circumvent legal restrictions prohibiting BATA, which can only borrow against toll-bridge revenues, from borrowing the money itself.)

Of the total $9.1 billion borrowed since 2001, $6.4 billion has gone into Caltrans’ project-construction fund. The rest was used to pay off earlier bonds, refinance existing debt at lower interest rates, pay the upfront costs of issuing the bonds, or maintain required cash reserves. By continuing to finance toll-bridge projects with revenue bonds, BATA ensures most of the debt will be repaid from what amounts to motorist user fees, not taxes—continuing to keep billions in debt off state balance sheets.

The variable-rate gamble

Historically, BATA has relied heavily on bonds with variable interest rates, which can make it hard to accurately predict financing costs. Some of those rates were established by auctions conducted on a weekly or monthly basis, with investors bidding on the interest they were willing to pay until the next auction. Since 2006, BATA has sold about $4.3 billion in bonds with variable interest rates, and another $570 million with rates at auction.

To stabilize interest payments on the variable and auction-rate bonds, BATA engaged in a sophisticated form of gambling called interest rate swaps. These financial derivates create “synthetic” or artificial interest rates by converting variable rates into fixed rates, and fixed rates into variable rates pegged to a predetermined index. The swaps themselves are contracts with financial institutions requiring one party to pay the other—depending upon which underlying interest rate is involved.

In essence, in an attempt to save money, BATA was betting which way interest rates would go. If a BATA swap involved a variable-rate-to-a-fixed-rate contract, and the variable interest rate rose above the fixed interest rate during the contract period, BATA would be required to pay the difference to its financial-institution partner. If the fixed rate exceeded the variable rate, the financial institution would pay BATA.

Many public agencies in California use these swaps, but in doing so take the risk interest rates won’t do what’s expected, or that one of the financial institutions that is a party to the swaps will somehow experience an event that forces a termination of the agreement, resulting in substantial penalty payments.

Earlier this year BATA was forced to pay one of its swap partners $104.6 million to terminate its swap agreements. The financial ratings of that partner, Ambac Financial Services, were downgraded, and BATA terminated the swaps because that downgrade not only increased the agency’s risk, but also because the downgrade pushed Ambac’s ratings below the levels the BATA board had mandated for its swap partners. Despite the termination payment, in August Ambac sued BATA in New York federal court, claiming the agency owed an additional $50 million. That lawsuit is pending.

In addition, Mayhew said BATA suffered losses of between $20 and $25 million due to the global financial problems of 2008, which caused the variable-rate auction market to cease functioning.

Since then, BATA has engaged in a series of refinancings and new bond issues designed to convert much of its outstanding variable-interest-rate debt to fixed rate. As of last month, the agency had $4.2 billion of its outstanding debt in fixed-rate bonds and just $1.4 billion in variable-rate securities. Prior to the refinancings, BATA had about $2.9 billion in variable-rate debt outstanding.

Uncle Sam lends a hand

One move made by Mayhew to reduce the amount of interest BATA itself will have to pay came last month, when the agency issued $1.3 billion in fixed-rate Build America Bonds, a growing trend among government agencies across the country. Mayhew says this program, where interest on the bonds is taxable, has given BATA access to a whole new range of investors that have never purchased the agency’s bonds before, including insurance funds, pension funds, and long-term liability funds.

“For once they”—investors—“have an asset that will match that liability,” Mayhew said. “They’re in heaven.”

Mayhew said the Build America Bond program, which is available until the end of 2011, is a “very powerful market,” and that he would have been remiss if he had not gone to the BATA board and presented this opportunity to wrap up the seismic financing (excluding the Antioch and Dumbarton bridges) at interest rates below five percent. “For forty-year debt, that’s an incredible number,” he said.

Although total interest due on the Build America Bonds between 2010 and 2049, when they’re retired, will be almost $3 billion, BATA’s actual share of interest payments will be slightly over $1.9 billion—with the difference being paid by the federal government in the form of a 35 percent rebate on interest. Every time BATA makes an interest payment to investors, the government sends a rebate check.

Mayhew said that’s a great deal. “The state of California pays far more in taxes than it gets back, so I don’t mind getting some of that back.” But Mayhew also recognizes BATA’s conflicting role in delivering to the state its largest civil-works project while at the same time delivering returns to investors.

“The way this is structured, the state takes a tremendous risk,” Mayhew said. “My obligation legally, is to the bondholders. My obligation contractually is to build these bridges. My purpose is to build bridges and safety features. My law says the first responsibility is to the bondholders. Caltrans takes a tremendous risk that we will honor our responsibilities.”

This story is part of a special reporting project that first appeared Dec. 8, 2009, in the San Francisco Panorama, a single-edition broadsheet newspaper published by McSweeney's. The project, conducted by SF Public Press, was researched and written by Patricia Decker and Robert Porterfield with the assistance of Mike Adamick, Andrew Bertolina, Richard Pestorich and Michael Winter. The project was supervised by Public Press director Michael Stoll. More than 140 people helped to fund this reporting project by donating through Spot.Us.