Amid intense lobbying to restore social-service funding to this year’s budget, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors earmarked $1 million for specific organizations, flouting the city charter.

The law, however, requires budget and “add-back” funds be directed to city departments, which can then disburse monies to nonprofit contractors.

After the mayor proposed a $6.6 billion budget with deep cuts to health and human services in June, the supervisors added back an unprecedented $43 million in spending, most of which went directly to city agencies. But private nonprofit groups, many of which have been contracted to provide city services for years, pushed hard to restore funding for particular programs addressing homelessness, drug addiction, mental illness and more.

The supervisors used a technical loophole to direct “add back” funding for at least one program by specifying a particular stretch of one street where the program is based. Supervisor John Avalos confirmed that the board restored a program at Mission Neighborhood Resource Center for the Homeless called “Ladies’ Night,” which provides homeless drop-in counseling and drug treatment services for women.

A July civil grand jury report published July 1 says this approach has become common practice in City Hall in recent years. While city officials say it is not technically a violation of the city charter, it sidesteps the intent of the law — to prevent the legislative branch from micromanaging public contracts. The so-called add-back process also empowers vociferous groups, not necessarily the effective ones, to lobby for their own continuation, critics say.

Add-backs, which start in early June after the mayor proposes a budget, are a political minefield for supervisors. They are lobbied heavily by community organizations, yet in the end are not supposed to identify specific nonprofits for restorations. Such “targeted” add-backs would violate the law, according to the city attorney’s office. If proven, they could lead to misconduct charges, though that has never happened.

“They are not allowed by the charter to interfere with the decisions as to who gets how much money and for what,” Monique Zmuda, the city’s deputy controller, said. “That is only for the department head. The reasons are that the board is supposed to be setting policy and not making a determination as to who is going to get paid how much.”

Budget line items go to department heads, who have authority over payment of nonprofit organizations. The board may only direct city departments to restore funding for services, and the department then chooses which nonprofits get the cash. The city charter is clear: The Board of Supervisors does not “have any power or authority, nor shall they dictate, suggest or interfere,” in the compensation or contract supervised by the mayor’s office or department heads.

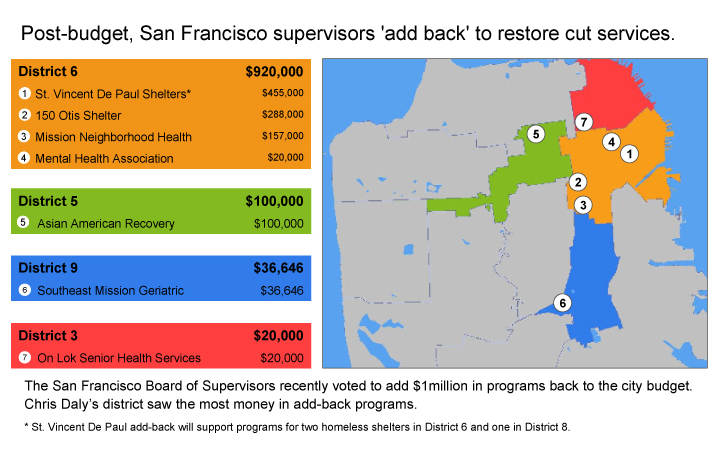

But the supervisors have specific groups in mind when they move money back and forth in budget season. In fact, this year they kept track of which organizations they wanted to fund on a chart meant for internal use. When it came time to vote on the appropriations, the references to specific organizations were removed from the public document.

Spending restorations are one of the few political tools available to disenfranchised communities and the public services that aid them, say supporters of the nonprofit groups.

Calvin Welch, an organizer with the Council of Community Housing Organizations, said that without the add-back process, there would be less funding for “elderly, the youth, people with mental and physical disabilities, people that on their own would have a very difficult time organizing and advocating for themselves.”

Squeaky wheels

The civil grand jury report found that add-back restorations circumvent the city’s process for identifying ineffective nonprofit organizations. If a city department eliminates a nonprofit group for being ineffective, but it has enough political influence with the board, it could have its funding restored, the report concluded.

Elizabeth Boileau, chair of the civil grand jury, said the restorations “upend” the city’s methods for managing nonprofits. “We found that add-backs should be stopped,” Boileau said.

A supervisor could be removed from office if his or her actions are found to constitute official misconduct, said Buck Delventhal, a deputy city attorney.

The add-back process comes after the mayor proposes a budget on June 1. The Board of Supervisors then has a month to produce a service restoration. This year, as the city faced a $438 million deficit and the budget-cutting process consumed the city’s governing infrastructure, the process was extended into late July.

The process often turns frantic as contract service providers lobby, and sometimes rally noisily, for their programs.

Many community groups with ties to service providers say the lobbying period is a crucial entree for poor and vulnerable social-service beneficiaries in the halls of power. The Coalition on Homelessness lists nearly $5 million in restorations that came from the Board of Supervisors’ Budget and Finance Committee, including nonprofit groups such as Tenderloin Health, Caduceus Outreach Services and SRO Families United Collaborative. The mayor was listed as restoring $2 million.

Targeted add-backs

Add-backs are one of the few ways the board can impact spending after the mayor proposes a budget, other than simply cutting programs. Yet publicly, supervisors disavow targeted add-backs.

“From my end, I’m not interested in telling the department to give money exactly to an organization,” District 11 Supervisor Avalos said. “If you look at our add-back list, we don’t mention specific organizations. We talk about departments.”

Supervisor Sophie Maxwell said she tries not to be specific with restorations: “You can get into problems with that. I think it’s wrong.”

But Maxwell acknowledged that when she first became a supervisor in 2000, the board used to target specific organizations outright. The process made supervisors uncomfortable and the board moved away from the practice, she said. Maxwell, who represents District 10, was chair of the budget committee in 2002.

She said she believed supervisors should be funding services, not organizations, and that the law should be more specific.

“If it isn’t against charter, it should be,” Maxwell said.

But the civil grand jury report suggests that supervisors veered toward a form of veiled earmarking, as opposed to providing funding directly to favored service providers.

Ladies’ Night

Every Thursday for the past five years, homeless and drug-addicted women – including some who work as prostitutes – have sought respite through the Mission Neighborhood Resource Center’s Ladies’ Night program. [ See related video by The Public Press’ Monica Jensen.]

The two-hour session is one of the city’s only drop-in events exclusively for women, offering needle exchange, counseling, massages, dinner and games. Laura Guzman, the center’s director, said the environment allows women to “feel safe from their boyfriends, johns and police.”

In past years, the board has used add-backs to create new funding for programs. Ladies’ Night was initially funded through grants, but in 2006 Guzman lobbied the Board of Supervisors and secured $150,000 for the program through budget restorations.

Since 2006, Mayor Gavin Newsom’s office has cut funding to the program twice, most recently last February. In both instances, after intense lobbying and protests by supporters, the board restored money for Ladies’ Night.

Deleted from documents

Records from this year’s add-back process support this claim. One chart from the board’s budget and finance committee – provided by the clerk of the board and time/date stamped 6 p.m. on July 1 – contains a column specifically for which community-based organizations should get add-backs. In this column, one entry reads, “Restores funding for Ladies’ Night,” and lists the Mission Neighborhood Health Center. The list also allocates $455,000 for three shelters run by the St. Vincent de Paul Society.

In another chart distributed to the media in the Board of Supervisors’ chambers, an hour after the timestamp on the first chart, the organization column is missing. For the Ladies’ Night line item, the entry has been changed to read, “Restores funding for comprehensive bilingual drop-in services to homeless women and men on the 16th Street corridor”— where the health center is located.

When asked whether Ladies’ Night was restored using a technical loophole, Avalos nodded his head.

“That was an effort to maintain that type of service in that part of town,” he said.

Avalos said community organizations were listed on the final chart to give the public a better idea of the services provided, but that the departments are not given names of any organizations to fund.

“This is the final list,” Avalos said, indicating the chart without specific organizations. “What goes out publicly and what goes out to the departments is different.”

Zmuda said that listing a specific group on the chart does not constitute misconduct. The official budget, which does not list specific organizations, is the legal document, she said. Delventhal, the deputy city attorney, agreed.

“If it is not in the budget, it is not binding on the departments,” Delventhal said.

Zmuda said that under Avalos, the board has been more focused on services than on specific organizations. She said that the detailed chart specifically naming Ladies’ Night was probably an early document used for identifying where services are most needed.

On the add-back chart, 12 line items reference specific programs, locations or projects. These add-backs total $2.1 million in funding.

Seven items are for social-service organizations, and the other five listed are city-funded programs or parks, which is permitted under the city charter. But even city-run programs lobby heavily. The users of a bocce ball and tennis court in the Excelsior District called Avalos for weeks until they were able to restore the $100,000 that had been slated for renovations there.

Charter’s imbalance of power

When the city charter was first written in the 1930s, the Board of Supervisors had no power over the budget, Zmuda said. The charter was rewritten in 1996 to allow the board to add and cut funds after the mayor proposes the budget. But the law still allows the mayor to veto proposed cuts, to choose not to spend — which Newsom has done repeatedly — or to cut the budget midyear, which the board has no way of challenging.

In 2008, Newsom issued midyear cuts in August, just weeks after the supervisors’ add-back list was released. The mayor never spent 41 percent of the board’s restorations.

“In essence we are subordinate to the mayor,” Supervisor Ross Mirkarimi said. “It makes it a tough challenge on a $6.7 billion budget.”

“For the mayor, making budget cuts is a really easy way of setting policy,” said Bob Offer-Westort, editor of the Street Sheet newspaper and a civil rights organizer for the Coalition on Homelessness. “He doesn’t have to negotiate with anybody.”

Funding for nonprofit service providers frequently comes between Newsom and the Board of Supervisors. The mayor’s office did not respond to repeated requests for comment, but supervisors were eager to talk about the broken budgeting process.

“It’s frustrating, it shouldn’t be that way,” Avalos said.

“Usually it takes a people’s budget coalition to prevent the mayor’s office from gutting human and health service programs,” Supervisor Eric Mar said.

To counter the power of the mayor, the board sometimes cuts funding for a program that is important to the administration; and vice versa. Offer-Westort calls this back-and-forth cutting a fiscal version of “mutual assured destruction.”

Winners and losers

Some supervisors criticize the restoration process, and community groups say the system is exploited by well-connected organizations.

“Many larger nonprofits, and nonprofits who have been around for a while, understand the landscape,” Mirkarimi said, adding that politically experienced organizations often win out. “It pits nonprofits against nonprofits in a way that I find barbaric.”

Welch, a veteran of city budget wars, says the groups that trumpet their cause most effectively are likely to reap the rewards: “The squeaky wheel gets the juice.”

Much of the deal making happens in committee. Supervisors on the budget committee, including District 9’s David Campos and District 5’s Mirkarimi “definitely had more of a voice for fighting for add-backs than other districts,” said Mar, who represents District 1.

“Being on the budget committee gives a supervisor tremendous advantage in getting what they want added back,” Mar said.

The July 1 civil grand jury report concurred, finding that in years past, targeted add-backs were often made in response to “political maneuvering.”

“In general, you need to [have] the chair of that committee with you,” Offer-Westort said. “So, you lobby. You go in and make your case. You do whatever you need to get heard.”