M any San Francisco officials are savoring what they see as a once-in-a-life opportunity to take over some or all of the electricity distribution from bankrupt Pacific Gas and Electric Co. to achieve progressives’ long-sought goals of power independence and 100 percent green energy.

“I will try to suppress my glee,” former Supervisor Sophie Maxwell said during her April confirmation hearing to join the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. “Power should be publicly held. It should be a public utility. It should not be for profit.”

In May, that enthusiasm got a double boost that could prove to be the tipping point in the decades-long, acrimonious marriage between the city and PG&E.

Initial Analysis Sees Benefits

The utilities commission released a preliminary report that concluded the long-term benefits of municipal power outweighed the costs and other risks, and that relying on PG&E “has grown increasingly untenable and unnecessarily expensive.” Days later, state fire officials blamed PG&E for the November blaze that destroyed the town of Paradise and killed 85 people, adding to billions of dollars in liability for previous disasters that drove the utility into court to reorganize under Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Already convicted of six felonies for the deadly 2010 San Bruno gas pipeline blast, the company could face more criminal charges for last fall’s blaze near Chico, in addition to further lawsuits.

But as local regulators push for greater or total electricity independence, some daunting realities confront the dream of a San Francisco free of the nation’s largest electrical utility and some of the highest rates in the land.

Previously: Report Says Benefits of Buying PG&E’s Grid Outweigh Costs, Risks

San Francisco already generates most of its own electric power but depends on PG&E for grid distribution to households, businesses and even city-owned properties. As the May assessment pointed out, buying the electrical grid could cost several billion dollars for starters and would be a complex, drawn-out process over years, with significant investment costs and risks. (The report did not address natural gas service.) The city’s top utility regulator has described PG&E’s aging infrastructure as “not in a state of good repair,” and upgrading the system could cost many millions. Along with the promise of cheaper, carbon-neutral power, ratepayers would face substantial insurance liability for any accidents or disasters within the municipal coverage area if the city takes over. Then there’s the cost of adding thousands of PG&E employees to the city payroll, along with the financial impact San Francisco’s departure could have on PG&E customers elsewhere in California.

Mayor London Breed, who nominated Maxwell, has all but pushed the city’s chips in for a municipal distribution system for the power San Francisco already produces through Hetch Hetchy Power and CleanPowerSF, which together provide 80 percent of the city’s electricity needs. She ordered sweeping studies of what it would take to buy the power grid and how much it would cost after PG&E announced in January that it would declare bankruptcy, following historic, deadly wildfires in 2017 and 2018. In April, the Board of Supervisors likewise called for such studies, noting that “the public interest and necessity require changing the electric service provided in San Francisco.”

‘Does It Make Financial Sense?’

The next step in the SFPUC’s assessment is evaluating the cost of system repair and operations, and calculating potential revenue from taking over PG&E’s distribution and transmission. For his part, City Attorney Dennis Herrera is analyzing the purchasing options and the legal complexities involved.

“Does it make financial sense? If it doesn’t, then we won’t do it,” said SFPUC press secretary Will Reisman.

Barbara Hale, assistant general manager of the commission, told the Board of Supervisors in January that the city’s overall costs would likely be lower than PG&E’s. “Our costs won’t include the profit component,” she said. “Our costs for operating and managing the system are lower.”

Neither PG&E nor the city’s public utilities commission has said exactly how much the grid is worth. PG&E does not report its value to the public, though it will have to make disclosures in bankruptcy court. Besides the commission’s ballpark of “a few billion initially,” Michael Wara, director of the Climate and Energy Policy Program at Stanford University’s Woods Institute for the Environment, has estimated the grid’s value at $3 billion to $5 billion. Other, less extensive scenarios for limited independence involve a partial buyout of the grid that could cost tens to hundreds of millions of dollars annually or at one time, depending on which facilities are purchased.

“These types of investments are only feasible if PG&E is willing to work cooperatively with the City,” the May report said.

Unique Tangle of Public and Private Systems

Testifying with Hale to the Board of Supervisors, SFPUC General Manager Harlan Kelly Jr. warned that the distribution system in San Francisco “is not in a state of good repair. We have to realize that if we look at what the value is, we have to discount it based off that.”

In filings with the California Public Utilities Commission, which regulates private utilities, PG&E warned that carving the company into smaller public utilities is fraught with complexity. Balkanizing its electric system, it warned, would be expensive.

The grid was built over a century with little consideration for municipal boundaries. “This overlap of San Francisco’s public and PG&E’s for-profit service is unique,” the SFPUC wrote in its 54-page May report. “No place else in California or nationally is there a patchwork of distribution facilities so intermeshed between a public utility and a private one.”

All of the substations, transformers and other grid assets would need to be divided up, potentially among several public utilities or new private companies. What if key substations or transformers are located outside of San Francisco and shared among multiple cities, counties or companies?

A Complicated Break-Up

“The valuation process, if it actually goes ahead with the transfer of assets on a piecemeal basis, is going to be an incredibly long and difficult process,” said Severin Borenstein, faculty director of the Energy Institute at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business. “We will be doing it with multiple parties, if we break up the utility, and that will be very complicated.”

In a high-density city like San Francisco, maintenance costs can be distributed across a large number of ratepayers. That’s not true in rural areas of the state where the risk of wildfire is much higher. Right now, the costs of wildfire protection are distributed among all of PG&E’s customers, but if San Francisco separated, it’s conceivable rates would go up for customers elsewhere.

“It may be the case that San Francisco customers would be winners if we break up PG&E into a bunch of municipal utilities,” Borenstein said. “I don’t know who wants to be the utility for Paradise or Chico.”

The SFPUC estimated that the city and its residents pay PG&E $300 million a year to deliver electricity. Of that, $75 million is the city’s share of PG&E shareholder profits and borrowing costs. The city also pays the company $60 million annually for statewide “public-purpose programs” such as energy conservation, low-income assistance and research and development, which “are often not tailored to San Francisco-specific building stock or demographic characteristics.” On the receiving end, the company pays $40 million a year in local taxes, fees and philanthropy.

Utility Blamed for Project Delays, Extra Costs

“Because PG&E is a direct competitor in serving San Francisco customers, its strategy has been to leverage its ownership of assets to impose unnecessary and expensive requirements on the city,” the report noted. That’s been particularly true since 2015, when the expiration of a 70-year-old interconnection agreement lifted restrictions on whom the city could serve. The report blamed PG&E for delays or excessive costs in 53 projects citywide involving “critical services” such as building affordable housing, and health, safety and accessibility upgrades. “In essence, the City is paying PG&E to build and upgrade its system, and then PG&E charges service fees for the City to use that system,” the report said.

In an emailed statement a day after the commission released its interim findings, PG&E spokesman James Noonan said, “We look forward to reviewing the City’s analysis, and appreciate the City’s open and transparent dialogue on the subject. We all agree on the importance of continuing to serve the citizens of San Francisco, clean, affordable, and reliable energy. PG&E has been a part of San Francisco since the company’s founding more than a century ago, and we are committed to working with the City and will remain open to communication on this issue.”

The company issued an identical statement weeks before the report was released.

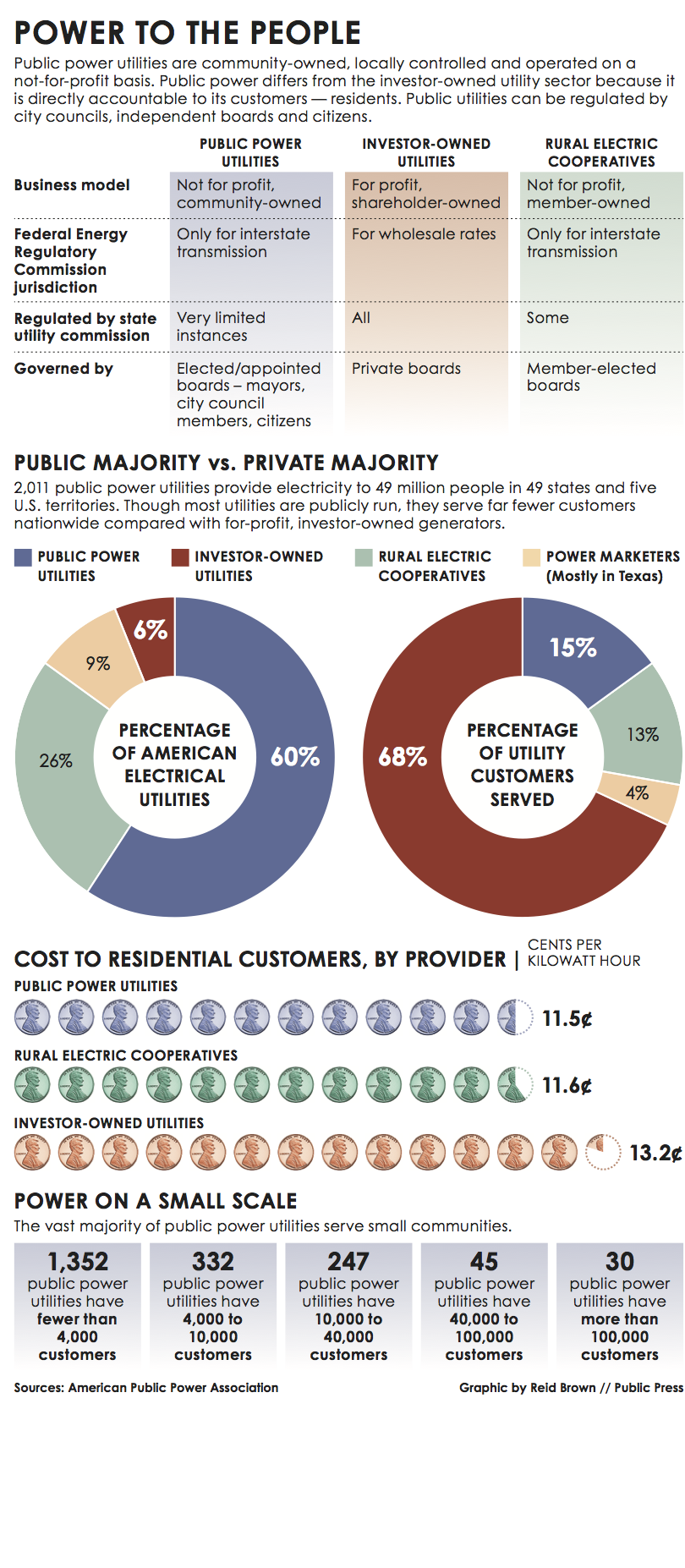

A quarter of California’s power is provided by 40 publicly owned utilities, which are organized into rural cooperatives, irrigation districts, city departments — like the SFPUC — and municipal districts. With 3.9 million customers, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power is the country’s largest municipal district. Sacramento adopted municipal power in 1946 and is the nation’s sixth-largest community-owned electric utility. The city of Alameda has been generating its own power since 1887, the oldest public electric utility west of the Mississippi River.

A Local ‘Green New Deal’

In February, surrounded by municipal workers and energy advocates, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti announced that his city would not spend the $5 billion originally allocated to rebuild three natural-gas power plants on its coast. “This is the beginning of the end of natural gas,” he said to a cheering crowd of municipal workers.

Los Angeles will phase out the gas plants, which together produced 11.4 percent of its electricity in 2018. Garcetti said the city will replace the generation with renewables, and it’s an example of how a municipal district can move nimbly without the oversight of state regulators. Unlike an investor-owned utility like PG&E, municipal power is not regulated by the California Public Utilities Commission. Voters, supervisors and the mayor would govern a municipal utility. A city-commissioned survey of 435 registered San Francisco voters in March found 68 percent supported municipal power for residents and business.

San Francisco District 9 Supervisor Hillary Ronen said a public utility can be a part of a local version of a “green new deal” to spur economic development and renewable energy generation. During a January Board of Supervisors meeting she said, “When profit motive is the ultimate motive, then public safety comes second. Then reliability comes second. Then keeping costs down comes second.”

“If we as a city are able to take over this responsibility as a municipality, profit motive will not be our ultimate goal,” she said. “Our ultimate goal will be to provide a clean product to our customers in a reliable way that controls costs and provides a public good — like a utility should be run. It is urgent that San Francisco has a complete divorce from PG&E as quickly as possible and takes over operation of this utility.”

The city has set an ambitious goal of delivering power free of greenhouse gases, without nuclear generation, by 2030. PG&E’s energy mix is dirtier than what the city produces from Hetch Hetchy and CleanPowerSF, so cutting the cord would make the transition “much less difficult.”

Experience With Renewable Energy

In June 2018, voters approved Proposition A, which creates a bonding authority so the city can develop solar, wind and other renewable generation projects. District 3 Supervisor Aaron Peskin led a drive for the ballot initiative with the goal of reducing the city’s carbon footprint. All 11 supervisors supported it.

Now, the SFPUC may issue revenue bonds to build clean energy generation projects, so long as two-thirds of the Board of Supervisors approves. City officials might use the bonding authority to pay for the upfront cost of buying PG&E equipment. If the bonding authority covers the upfront costs, ratepayers could pay for it over time.

In 2016, the SFPUC launched CleanPowerSF, a not-for-profit program that acquires energy on behalf of its customers. They may choose between a baseline “green” program, which delivers 48 percent of power from renewable sources, or a higher-priced 100 percent renewable mix. By year’s end, most San Francisco customers — more than 360,000 — will be automatically enrolled in CleanPowerSF, though they may opt out and stay with PG&E.

For the past 100 years, San Francisco has generated hydroelectric power through its Hetch Hetchy Power System, which today powers 17 percent of the city, along with Muni, San Francisco General Hospital and San Francisco International Airport.

These two clean-energy programs deliver most of San Francisco’s electricity needs, but the power still reaches the city over PG&E’s wires. Ronen and Peskin complain that, year after year, PG&E spends millions on lobbying and other measures to try to block the city’s public-power plans.

PG&E’s Financial and Criminal Troubles

PG&E has been blamed for several of the most destructive fires in California since 2015. The financial liability from the wildfires has saddled the investor-owned utility with billions more in debt and left it scrambling to contain the political and financial fallout. Recently, the utility overhauled its leadership while pursuing a tumultuous bankruptcy in which it claims $51.7 billion in debts and $71.4 billion in assets. For the first quarter of 2019, the company said its income dropped nearly 70 percent because of the Camp Fire and the resulting bankruptcy filing.

PG&E wants regulators to approve spending $2 billion on a “smart” grid and wildfire prevention measures. The plan includes clearing brush and branches from 120 million trees near 81,000 miles of high-voltage power lines, installing 600 high-definition cameras and building 1,300 weather stations to better predict fires. A former federal judge is monitoring PG&E’s efforts to improve safety.

In a related move, in late April U.S. District Court Judge William Alsup, who is supervising the company’s felony probation related to the San Bruno explosion and fire, ordered the utility to not reissue dividends and to direct the shareholder payouts to wildfire prevention.

PG&E’s new CEO, William D. Johnson, was set to receive more than $20 million a year (salary, signing bonus, future severance and severance pay from his previous utility). That largesse, on top of other outrage-generating events — $235 million in court-ordered employee bonuses in the wake of the company declared bankruptcy, massive fires caused by PG&E negligence, power outages and explosions — has kept resentment against the regulated private utility burning red-hot among local voters and their representatives.

Fires and Explosions in the City

In filings with the state PUC, City Attorney Herrera argued that PG&E was failing to keep people safe and has broken “a variety of federal and state criminal laws.” He listed a series of PG&E mistakes that resulted in fires and explosions in San Francisco.

In 2003, PG&E’s Mission Substation caught fire, knocking out power to 100,000 customers. The utility had to pay $6.5 million to settle a state complaint for its role. In 2005, an electrical short in a PG&E underground power transformer set off an explosion and sent a manhole cover flying 30 feet in the air. The explosion broke a woman’s arm and she suffered serious burns across her body.

The list goes on: A PG&E electrical vault exploded at O’Farrell and Polk streets in 2009, and the fire burned for two hours. That same year, an electrical malfunction elsewhere in the city caused an underground blast.

“The commission should recognize that public ownership and local control of utility service has traditionally offered safe and reliable service with greater transparency, accountability, and fiscal and societal responsibility, and all at lower rates than service from investor owned utilities,” Herrera wrote. “The time has come for the commission to support and encourage the replacement of service from PG&E with service from local publicly owned utilities who choose to provide that service.”

Not everyone agrees. The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers represents PG&E workers and opposes a PG&E breakup. The union says a city takeover of PG&E would only further complicate California’s energy challenges. Tom Dalzell, a union representative, said the plan is “somewhere between bad and very bad for our members.”

He also disputed claims that PG&E neglected the power grid in San Francisco. “Any utility anywhere could always use some improvement, but I don’t think San Francisco has really suffered in terms of the grid,” he said. “I think the SFPUC is negotiating with PG&E, and the city is trying to knock billions of dollars off the system. I think they are taking a negotiating position.”

Senior editor Michael Winter contributed to this article. An earlier version appears in the summer 2019 print issue of the Public Press, which can be purchased at select retail outlets or by mail.