This story and the “Civic” episode should be considered opinion and not an official view of either “Civic” or the San Francisco Public Press.

“History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme.” While the remark may or may not have been made by Mark Twain, it certainly rings true as we compare the 1980s with 2020, when an incompetent response to a pandemic and a minority’s call for justice brought people to the streets.

The callous eight minute long killing of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer in the midst of a pandemic has been the catalyst for a worldwide demand for police accountability and long denied racial justice.

The events have a certain rhyme with the 1980s. The callous disregard for an epidemic that was initially killing despised minorities spurred the LGBTQ community and its allies to action, with street protests by the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT-UP) and the half a million person Lesbian and Gay March on Washington in 1987.

As a young man I volunteered with the media relations department. Three days of protest that October included a march from the White House to the Capitol, a marriage ceremony for lesbian and gay couples and mass arrests at the Supreme Court which had just ruled sodomy laws — which punished LGBTQ people — were constitutional. We were effectively criminals in most U.S. states.

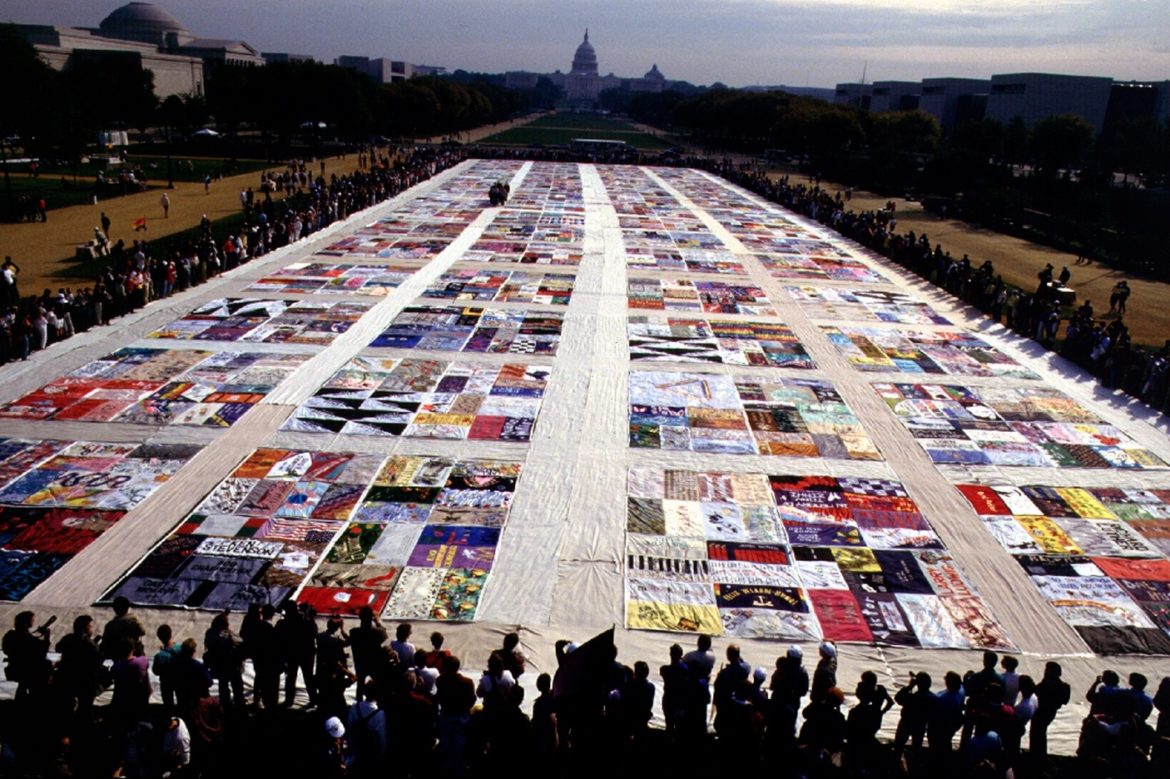

The most powerful demonstration was the silent witness of the AIDS Memorial Quilt, begun by activists in San Francisco in 1985. By 1987, it filled the Washington Mall with thousands of 6 foot by 3 foot panels bearing the names of those who had died from AIDS. It was a rebuke to the Reagan Administration which had first ignored and then underfunded HIV prevention and treatment.

When I passed near the quilt I had wondered what my panel would look like, assuming (rightly) that I too had been infected and would likely die well before I was 30. Due to luck and medical advances I have lived to see another era of protest and pandemic.

Today COVID-19 is disproportionately taking the lives of minorities. The economic and social dislocation has once again created a wave of demand for change and an end to police brutality against African Americans.

In February, the AIDS Memorial Quilt returned to the Bay Area after being moved to an Atlanta warehouse in 2001. At the time, It seemed likely to be little more than a historic footnote, a reminder of a darker time. It was again to be unfurled, this time in Golden Gate Park in April, but the arrival of the coronavirus changed everything.

At the quilt warehouse in San Leandro in February, I interviewed John Cunningham, executive director of the National AIDS Memorial Grove which cares for the quilt. He explained why he believes the AIDS Memorial Quilt speaks to the current generation.

“I think it’s important to remember that the AIDS crisis was the intersection for many different social movements, whether it be individuals of color, whether it be access to health care, whether it be poverty, whether it be LGBT, whether it be substance abuse, all of those different movements intersected in this one particular epidemic. And with that being the case, we feel that it is appropriate to take into leverage the lessons of the epidemic, and to be able to identify the best practices of social movements. So that, in the future, social movements will not have to go through the painful and arduous process that we did, which was trying to figure out how to get the attention of a nation and how to start to save people’s lives.” — John Cunningham