For most San Francisco tenants, higher rent is a yearly fact of life. Those fortunate enough to live in rent-controlled apartments get some pain relief from city regulations that limit annual increases.

But despite protections for those tenants, the rules still allow for unexpected increases that can be ruinous to older, lower-income and minority tenants who have been in their apartments for years.

For nearly four decades, San Francisco’s rent-control regulations have permitted landlords to delay, or bank, an unlimited number of the allowed annual rent increases and apply them any time in the future — all at once if they would like. These banked increases never expire, even after a new landlord buys the building.

Tenant advocates say banked increases catch renters by surprise and increase financial pressures that can push them out of their homes.

“They’re suddenly faced with these large increases and can’t pay them,” said Tommi Avicolli Mecca, director of counseling at the Housing Rights Committee of San Francisco.

San Francisco politicians show little interest in addressing this, unlike those of other Bay Area cities. This summer, Alameda lawmakers passed regulations intended to maximize tenant protections without disrupting landlords’ ability to make a profit.

Mecca estimated that 10 to 12 people a month seek his organization’s help primarily because of banked rent increases. They mostly are “living on a fixed income or Social Security or a pension or something, where that 10 years of rent increases are going to be a burden,” he said.

“I think it is a big deal when a building is sold. That’s probably the situation we find most often,” Mecca said. “The new landlord comes in thinking, oh, this is a good way to get a little extra money on an apartment.”

Fifty-seven percent of Bay Area senior renters have personal incomes inadequate to afford necessities like housing, health care, transportation and food, according to a 2015 study by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of British Columbia.

Because the San Francisco Rent Board doesn’t track when landlords apply banked increases, there is no data on how common the practice is across the city’s roughly 172,000 rent-controlled housing units. Key information about affected tenants — age, duration of tenancy or whether the increase caused displacement — is not tracked.

To the landlord, a banked increase is merely a delayed increase that’s inevitable, and “rent increases are a lifeline to survival for a lot of our members,” said Charley Goss, government and community affairs manager at the San Francisco Apartment Association, a landlords organization.

Tenants “are better off in the long run if the owner banks their increases,” Goss said. When an increase is banked, it means the tenant is saving money by paying less than the landlord is allowed to collect. Even when a banked increase happens later, the tenant keeps those savings.

“Whether they budget or not is a tough thing. But, quite frankly, it’s not the role of the landlord,” Goss said.

Noni Richen, landlord and president of the Small Property Owners of San Francisco Institute, said that like tenants, many landlords of rent-controlled buildings are perched on the financial edge. “Most people do the increase every year, and they need every penny,” she said.

But she defended the practice of rent banking.

“I think that I’m sort of a free-market person. I think it should be available,” Richen said. She recalled a particularly good tenant who had a low income and was on disability. She said she wanted to retain him, and knew that he would have struggled to afford any type of increase, so “we just opted not to do it.”

Every year, the city’s Rent Board tells owners of rent-controlled buildings the maximum percentage that they may raise rents, based on fluctuations in regional inflation. Over the last decade the median annual limit was 1.9%, and this year’s limit is 2.6% through February 2020.

Here’s how a banked increase would work: If someone paid $1,000 per month in 2009, and the landlord banked all subsequent rent increases, then in 2019 the monthly rent could rise by a maximum of $153, or about 15%. That’s an additional $1,836 for the year.

Though such an increase would likely be negligible for many working in tech, finance or other highly paid professions, it could prove daunting to seniors or low-wage earners struggling to make ends meet.

Tenants can actually wind up paying more when landlords layer other legal increases — such as so-called pass-throughs.

Pass-throughs let landlords recoup costs for such things as electrical work, mandatory seismic retrofits or additional property taxes resulting from voter-approved bond measures. Many of these levies are temporary, though others can last years or be permanent. Landlords must often petition the Rent Board for pass-throughs. The board reviews those requests, and may exempt tenants who prove financial hardship.

Not so with banked rent increases, which cannot be blocked because of a tenant’s financial situation.

Landlords don’t have to notify the Rent Board or get its approval to apply these raises, but they are supposed to give tenants documents explaining the underlying math. Landlords also don’t have to notify tenants annually when passing up an increase or inform them that banked rents could be collected in the future.

Actually, no one gives tenants a heads-up about this possibility — including the Rent Board, which does not provide tenants information about how banking works.

“And I doubt anyone would read it if we did,” said Robert Collins, the board’s executive director.

Tenants are on their own. They can petition the board to see whether a banked increase is illegal if, for example, it’s greater than the accumulated percentage of the foregone annual increases.

Alameda Rethinks ‘Banking’

San Francisco is one of 10 Bay Area cities that control rents — there are at least five others statewide — though policies vary, according to a 2018 study by the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley. All are subject to the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, which restricts cities’ abilities to enact or expand rent control.

The city of Alameda, which adopted rent control in 2016, offers a sharp contrast to San Francisco regarding rent banking.

In April, the Alameda City Council tasked staff with researching best practices in other cities for how to craft a rent-control program almost entirely from scratch. On July 2, the council reviewed those findings and deliberated late into the night.

Perhaps the most contentious question: How to set the rules on rent banking to prevent abuse by landlords and benefit low-income tenants?

They were divided on even allowing it.

“I actually don’t like the idea of banking,” said Councilwoman Malia Vella, arguing it would effectively push out tenants who couldn’t afford the increase. “OK, you’re going to get a 6.5% increase this year. And next year you’re going to get another 6.5% increase. … I don’t know who is able to afford 6.5%.”

Vella advocated giving landlords a simple choice each year of raising rents or not.

But Vice Mayor John Knox White argued that the city would be “cutting off our nose to spite our face” if it didn’t allow banking, because landlords would be more likely to take the maximum increase every year.

“Banking incentivizes landlords to lower the rent now, with a possibility that they might go back up to where they would have been” in the future, White said. “The renter who had a landlord who banked for three years, that renter has paid significantly less year over year.”

Mayor Marilyn Ezzy Ashcraft said she wanted to limit how much of a banked increase a landlord could impose each year. City staff had recommended a 5% ceiling, but Ashcraft said that “strikes me as a little high,” because it would be in addition to the regular annual increase that the landlord could impose.

Vella agreed that 5% was too high. So that renters were never caught by surprise, she suggested allowing banking only when tenants consented.

White pushed back. “I just think that makes it too complicated,” he said, adding that the inconvenience might discourage landlords from banking at all.

Ashcraft laughed. “OK, um, so this is a little more complex than I was hoping.”

Councilman Tony Daysog opposed the whole rent-control program that was being considered. He presented U.S. Census Bureau data showing that, for almost all years from 2005 through 2017, most Alameda renters on average paid less than 30 percent of their incomes on rent. People paying beyond that proportion are considered “burdened” by housing costs, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

“That’s the data that really we need to focus on, because that’s telling a story that landlords, for the most part, are doing their level best to provide affordable rents,” said Daysog.

After 3½ hours of debate, the council voted 4-1 for several restrictions on banked increases for a rent-controlled tenancy:

- Landlords must notify City Hall of every banked increase.

- A landlord’s total bank may grow to a maximum of 8%.

- In a single year, landlords may draw from their bank to increase the rent by a maximum of 3%. This is in addition to the regulated base annual increase — which, like San Francisco’s, is calculated on regional inflation.

- Banked increases may not occur in consecutive years, and cannot happen more than three times during the same tenancy.

- The bank of unapplied increases zeroes out when a building is sold.

Alameda was inspired by other cities’ policies, some of which were relatively new.

As of 2018, Richmond landlords can use their banked increases to raise tenants’ rents by up to 5% in a single year, layered on top of the base annual increase that the Richmond Rent Board has issued. But in years when the board’s allowed increase already surpasses 5%, landlords can’t tap into their banks at all.

And in 2016, Mountain View legislated that the annually allowed increase, plus any banked increases, cannot raise a tenant’s rent more than 10% in a single year. Banked increases are voided when a building is sold.

Unfettered in S.F.

San Francisco, by comparison, can be seen as the Wild West of rent banking.

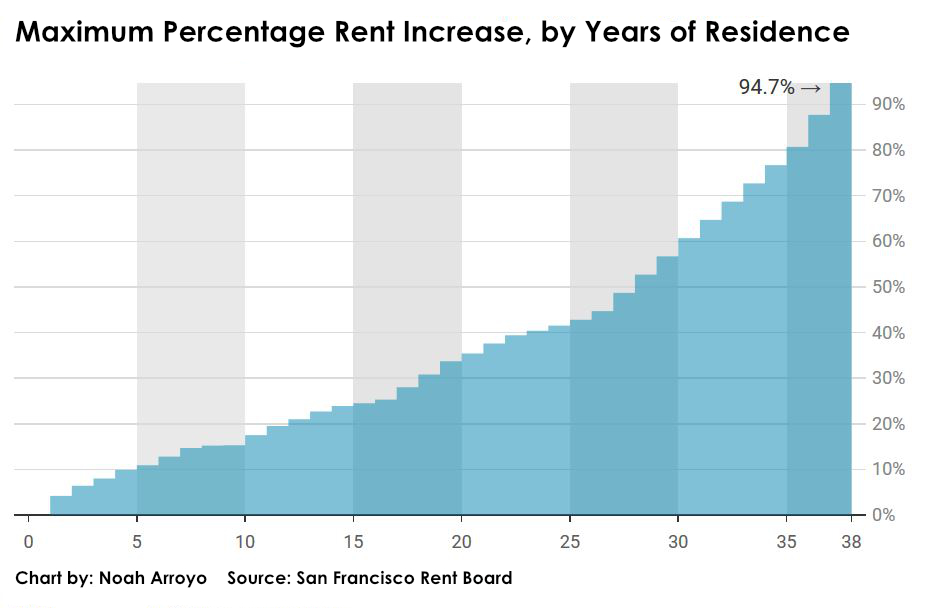

There’s no limit on the amount of banked increases, which can stretch all the way back to 1982, when the current policy was in place. Landlords may grow their banks to any size, and may tap into any portion of that bank in a single year, as long as they provide 60-day notices for increases surpassing 10%. That means a landlord who never raised the rent in the past 37 years could impose a non-negotiable hike of 95% in 2020.

!function(){“use strict”;window.addEventListener(“message”,function(a){if(void 0!==a.data[“datawrapper-height”])for(var e in a.data[“datawrapper-height”]){var t=document.getElementById(“datawrapper-chart-“+e)||document.querySelector(“iframe[src*='”+e+”‘]”);t&&(t.style.height=a.data[“datawrapper-height”][e]+”px”)}})}();

And when a rent-controlled building is sold, the previous owner’s banked increases pass to the buyer. This especially irks Mecca of the Housing Rights Committee.

“I feel like, if a landlord decides not to take a rent increase, then why should a new landlord be able to go back and take it? I don’t understand the rationale,” Mecca said.

“Because Prop. 13,” said Goss of the Apartment Association, referring to the 1978 state ballot measure that caps annual property-tax increases. Reassessments occur when real estate changes hands.

“OK, so I bought my building in 1965, my property taxes were capped in 1978, when Prop. 13 passed. You buy it from me, and yours aren’t,” Goss said. “It’s going to cost you potentially twice as much to run that building, just because of the property taxes.”

What if the buyer could no longer inherit the increases, making it more difficult to break even? “The worst-case scenario would be disinvestment in San Francisco,” Goss said. “It’ll just be people not buying these buildings and then not maintaining them.”

But Mecca said it’s the giant corporate landlord Veritas Investments Inc., not individual buyers, that he and his colleagues have seen capitalizing on banked increases.

“Sometimes I think that might be a business model,” Mecca said. “You buy a building, you know that the rents are low, there’s a good number of long-term tenants, so you buy with the idea that you’re going to do a banked increase” in concert with other types of rent pass-throughs.

“What I’ve seen is, a new landlord comes in and they immediately hit the tenant with everything at once,” Mecca said. Landlords win either way — tenants generate more revenue or get priced out, making way for people who will pay much more. In rent-controlled units, rents may rise to the market rate when new tenants move in.

Mecca said the cumulative rent hikes can blindside a tenant on a tight budget who has been “counting on the generosity of the landlord” for years before finding themselves with a new owner.

Veritas did not directly address these claims.

“For decades, San Francisco residents have been and continue to be able to enjoy the benefits of a rent-controlled rent,” a spokesman said via email. “That’s designed to be fair to residents and fair to property owners who operate the properties to exacting city, state and Federal requirements.

“We at Veritas are committed to the happiness of every one of our Residents, we welcome every Resident to stay in their apartments as long as they wish, and we work with every Resident who raises concerns of affordability.”

Veritas is the target of a lawsuit by 106 of its tenants, living in 39 buildings, who allege that the company fosters poor living conditions in order to push long-term residents out. Veritas denies the allegations.

See also: Complaints and Citations Rise Sharply at Veritas Apartments Cited in Lawsuit

For all our coverage on the corporate landlord, go here.

Political Inertia

Why did San Francisco sculpt its banked-rent policy this way?

“There was a bit of a learning curve,” said Polly Marshall, appointed to the Rent Board in 1984 by then-Mayor Dianne Feinstein. Marshall had a background in housing-policy activism and had begun a career practicing law, specializing in affordable-housing finance and development.

On the Rent Board, Marshall was one of two commissioners appointed to seats reserved for tenants. Two others are landlords, and a fifth commissioner is considered neutral. She served on the board until April, when Mayor London Breed chose not to renew her term.

Marshall said the city’s rent banking policy was the brainchild of politically centrist Supervisor Louise Renne, who wanted to make landlords feel comfortable foregoing rent increases by giving them the option to impose them later.

“It really was seen as tenant-protective,” Marshall said. Back then, “it wasn’t the professional gigantic landlords that are dominant today and are using the banking in their purchase or sale agreements.”

If the city supervisors were interested in revisiting rent banking, they would logically first ask the Budget and Legislative Analyst’s Office to research other cities’ approaches. But to date, no such request has been received, said Fred Brousseau, the office’s director of policy analysis.

The Public Press asked all district supervisors whether this was on their agendas. Three of their offices responded.

“In the year that we’ve been here, I haven’t heard a ton about this” from constituents, said Juan Carlos Cancino, legislative aide to District 5 Supervisor Vallie Brown.

“We have no plans to take any legislative action on this topic,” said Ivy Lee, legislative aide to board President Norman Yee, who represents District 7. “We have very little constituent contacts in regards to any displacement as a result of the banking of rent increases.”

Supervisor Hillary Ronen, representing District 9, said that “this has not been an issue that we have heard many complaints about from our constituents.”

Mecca, however, said the problem is real. “If the city is really serious about stopping displacement, the city’s got to look at the whole pass-through and banking thing,” he said. “Something has to happen here.”

Changing the policy might not even be controversial.

Goss said he could envision landlords surviving without banking as long as the city didn’t void unimposed banked increases.

Richen agreed that rent banking is not a crucial tool, and added that it in fact can carry financial risks for the landlord.

She cited her experience of about a decade ago, when her tenant petitioned the Rent Board to review his rent. The board found it had been too high — Richen said the discrepancy was slightly more than $100 for the time he had rented from her — and she had to repay him three years’ rent, or about $8,000.

That was the last banked increase she attempted. “We learned our lesson,” she said

Correction: An earlier version of this article erroneously stated that Noni Richen had overcharged her tenant by $100 per month for the period that the Rent Board reviewed. The error was corrected on 9/16/2019.

This story was featured in our summer 2019 print edition. Buy it here!