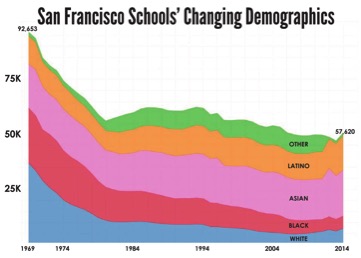

Racial segregation in San Francisco public schools is back in the news. For parents, however, it’s never gone away.

School Board commissioners Matt Haney and Rachel Norton, and Vice President Stevon Cook, will ask the board Tuesday to end the system the district has been using since 2008 to place students into elementary school.

The resolution will call for Superintendent Vincent Matthews to develop a “community-based student assignment system” that guarantees students a seat in diverse schools near their homes. Students already enrolled would not need to change schools.

The proposal, outlined Thursday, cites certain “rights” for families. It calls for a ”human centered process” with school options and information that’s online and multilingual. The final choice would be up to a family.

If it passes, the resolution would not immediately affect policy — and Haney, the board president, might not even be there to implement its vision for desegregating city schools. He’s in a three-way race for the District 6 Board of Supervisors seat, which represents the Tenderloin and South of Market neighborhoods. His opponents are YIMBY activist Sonia Trauss and former planning commissioner Christine Johnson.

The placement system is a complex mixture of luck and choice that has failed to desegregate city schools, as the Public Press reported in our award-winning 2015 special report, Choice Is Resegregating Public Schools. Many parents derided the system as “the lottery.”

We found that the placement system was failing its No. 1 goal of fostering racially diverse classrooms. At the time, a single racial group constituted a simple majority in six out of 10 schools.

In the years leading up to our report, racial isolation had grown. In the 2010-2011 school year, 23 schools had student bodies with a single racial group that made up at least 60 percent. By 2013-2014, 28 schools fit that description. Haney and Cook’s resolution states that, by 2015-2016, that number grew to 30 schools, though district documents show it has recently decreased.

Why has racial segregation persisted in San Francisco’s public schools?

“Money is the key factor,” wrote Jeremy Adam Smith, lead writer of the winter 2015 investigation. Wealthier white families had migrated from public to private schools. And in the public schools, “Parents are asked to navigate a system that is essentially a competitive marketplace, where affluence confers advantages.”

The system gives placement preference to children who:

- Have siblings already at a particular school. (That would not change under the Haney-Norton-Cook proposal.)

- Are enrolled in an attendance-area pre-kindergarten.

- Come from a neighborhood where the average test scores are low.

- Live in the school’s attendance area.

But parents can get their kids into schools where they would not automatically be placed by stating that preference, if openings exist. The system therefore appears to favor parents who can afford to spend the time and energy to research their options and submit their preferences to the district on deadline, gradually concentrating students in schools based on demographics and socioeconomic background.

One family interviewed by Smith, the Tanabes, said they had ranked all 72 elementary schools in order of preference. They made their selections with the help of a five-tab spreadsheet — shared by an informal network of affluent, educated parents — showing information on test scores, enrichment activities, language and after-school programs for all schools.

Smith interviewed another parent who had no such advantage: an undocumented immigrant who was learning English and had neither a computer nor an email address. Her child’s placement process was simple: “I went in person to the school district, and they told me that Bryant was my neighborhood school,” she said.

Read the special report here.

And expect more reporting from us on this issue.