Far fewer charged than across the region, even with strongly worded ‘no-drop’ guidelines

In January 2010, police in the Richmond District responded to a call from a woman who said her ex-boyfriend threw a broken vase at her, punched her and choked her, shouting “I am going to kill you!” The officers reported that when they tried to handcuff the apparently intoxicated man, he took a swing at one of them.

But despite physical evidence, photos and a taped interview with the alleged victim, the District Attorney’s Office declined to prosecute on any of the 10 charges against the suspect. In court records, prosecutors said they dropped the case because the victim withdrew her complaint.

Later that year, the court dismissed charges against the man in another domestic violence arrest. In a third incident a few months after that, prosecutors dropped charges of causing injury and violating a restraining order, citing “lack of evidence.”

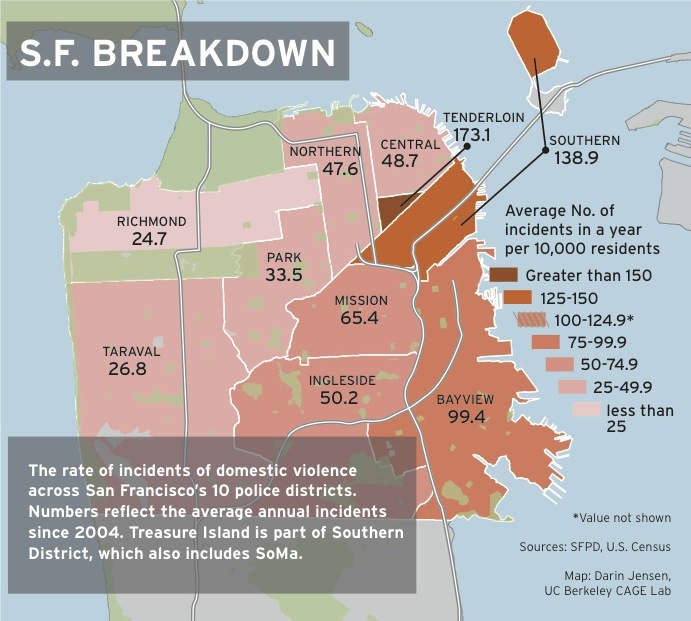

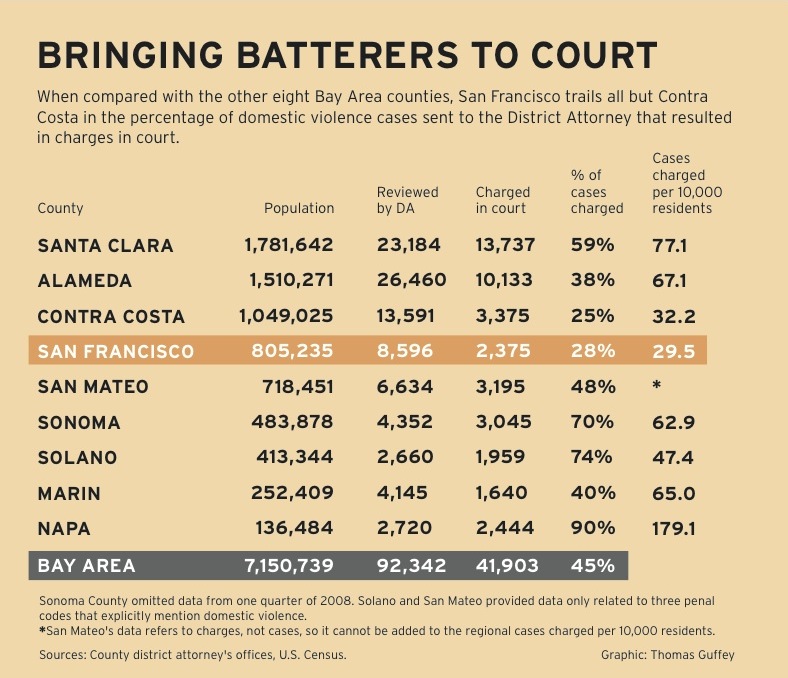

Though San Francisco’s so-called “no-drop” policy requires pressing domestic violence charges when evidence is sufficient to convict — even when victims refuse to testify — prosecutors here decline to bring the great majority of cases to court. Over the last half-decade, the District Attorney’s Office pursued just 28 percent of cases through to trial or plea bargaining.

Across the Bay Area, seven of eight other counties brought higher percentages of domestic violence cases to trial. Summing up all cases in the region over a similar period, court charges were filed 45 percent of the time. (Contra Costa’s rate was 25 percent, roughly tied with San Francisco’s.)

On a per-capita basis, San Francisco ranked last among Bay Area counties in per-capita prosecutions for domestic violence — 29.5 per 10,000 people — about half the rate for the whole region.

Except in rare circumstances, prosecutors in San Francisco are required to bring cases to court if they believe they can persuade a jury “beyond a reasonable doubt” to convict.

No-drop policies are designed to protect victims who fear retribution from batterers if they call police for help. In many domestic violence cases, the batterer has been at it before. And all too often a series of beatings can have deadly consequences. Half of all murders of women in California are the result of domestic violence.

Authorities across the state have adopted similar policies, arguing that aggressive prosecution disrupts patterns of escalating abuse.

“When you are dealing with this intimate relationship, we still have to try,” said Rolanda Pierre-Dixon, an assistant district attorney in Santa Clara County, who in 1991 established one of the first domestic violence units in the country. “If we don’t, something worse is likely to happen. We need to get away from the mentality that the victim drives the case. We drive the case, even in the face of the victim.”

San Francisco’s “no-drop” policy made headlines early this year in the domestic violence prosecution of Sheriff Ross Mirkarimi, stemming from a dispute in which his wife’s arm was bruised. District Attorney George Gascón said he pursued charges despite the wife’s denial that any abuse occurred and her resistance to cooperating with police.

In March, when Mirkarimi pleaded no contest to one charge of false imprisonment, Gascón said at a news conference that he would aggressively prosecute cases of abuse in the home. “Domestic violence will not be tolerated, no matter who the perpetrator, no matter who the victim,” Gascón said.

But records show that in thousands of cases, the San Francisco District Attorney’s Office has declined to prosecute. In the last five years, the district attorney’s domestic violence team reviewed about 8,600 criminal cases. Of those, the they dropped about 6,200 before court. About 600 resulted in a referral to parole or probation; cases dropped for other reasons -— such as further investigation, a complaint withdrawn by the victim or lack of evidence -— were not enumerated in city records.

Prosecutors across the Bay Area reviewed a total of more than 92,000 such cases between 2007 and 2011, and charged nearly 42,000 cases. (Two caveats: This five-year period differs because the city used to record data by fiscal year. Also, some counties counted specific charges, not cases.)

Small and large counties alike reported higher per-capita numbers of prosecutions for domestic violence than San Francisco, the lowest, with 29.5 charged cases per 10,000 residents. The highest was in Napa County, with 179.1 per 10,000 residents. The regional average was about 58.5 per 10,000.

San Francisco’s percentage of domestic violence cases prosecuted has fallen 1.5 percent during the year-and-a-half tenure of Gascón, who was previously the city’s chief of police. He succeeded Kamala Harris when she was elected state attorney general.

After a month of repeated requests for an on-the-record response, Assistant District Attorney Alex Bastian declined to comment specifically on the statistics his office issued under a California Public Records Act request, but he issued a written statement: “Domestic violence cases are notoriously difficult to prosecute. Victims frequently recant, and depending on other evidence the cases can be quite challenging. We only charge a case when we have a good faith basis to believe that we can prove the case beyond a reasonable doubt.”

The office’s policy on domestic violence endorses the concept of “victimless prosecution.”

It states: “As long as the remaining evidence is sufficient to prove the matter beyond a reasonable doubt, domestic violence and stalking cases shall proceed whether or not the victim chooses to participate.”

That’s the policy. But bringing real-world criminal cases through the legal system can be much more complicated, experts said.

“There is a culture in every community of how things are done,” said Eugene Hyman, who served as a judge in the state Superior Court judge in Santa Clara County for more than 20 years. Speaking generally about challenges prosecutors face, he said, “If there are disproportionate statistics on arrest and the refusal to issue, either you have timid prosecutors or the police are not doing their job or both, and prosecutors need further training.”

He added: “The police and the prosecutor work extremely closely. If there is a training issue, then usually the prosecution will say to the police — privately — that there is a problem here.”

Terry Spitz, chief assistant district attorney in Monterey County, said prosecution statistics vary from county to county for many reasons. Aggressive law enforcement might lead to a profusion of “marginal or questionable cases,” and thus a higher rejection rate. More restrained enforcement, on the other hand, can weed out weaker cases.

District attorneys also need to be mindful that they could spread themselves too thin if they try to litigate every case put in front of them: “Prosecutors should not be filing cases they can reasonably expect will be rejected by their local juries,” Spitz said. “Filing such cases is a waste of scarce court and law enforcement resources.”

Disturbing Incident

The Police Department produced more than 100 pages of domestic violence case files in response to records requests. The reports detailed several incidents the district attorney declined to prosecute for lack of evidence or uncooperative victims. The names of the victims were blacked out to preserve their privacy. For similar reasons, the Public Press is withholding the names of those who were arrested but not prosecuted.

The Richmond District incident in 2010 was the first of three times the police responded to a domestic dispute with the same man.

When two officers arrived at the apartment, the man answered the door. “This time she called the police,” he told them.

Inside they found a middle-aged woman soaking wet and struggling to breathe. They calmed her down, and she told them about the attack. The bedroom was in disarray. She said in a taped interview that the man, 53, broke a vase and threw the bottom half at her, hitting her left arm. He then threw a champagne bottle, but she moved to the side of the bed to dodge it. He pounced on top of her and choked her, she said. Eventually he stopped, punched her twice, threw water on her and ripped her shirt.

The officers immediately went outside to arrest him. With one wrist in a handcuff, he swung at them with his elbow, according to the report. The officer blocked the blow, punched him and guided him to the ground, they said. He was taken to Richmond Station and booked on 10 charges, including resisting arrest. The woman spent the night in a shelter.

Police evidence included 19 photos of the scene and the suspect, the shattered vase, the champagne bottle and the interview tape. But after the police’s Special Victims Unit investigated and forwarded the case to the District Attorney’s Office, the lawyers chose not to prosecute, said Ann Donlan, communications director for the San Francisco Superior Court. In legal documents, prosecutors said the woman withdrew her complaint.

There were two other abuse incidents over the next 14 months.

In November 2010, police again responded to a 911 call from the apartment. The woman recounted to the officers that the man, after catching sight of her ex-husband earlier in the evening, punched her arm, abdomen, stomach and back with both fists. He pushed her up against a closet and used the scarf around her neck to choke her. The woman fought back and scratched his face. She ran across the room to call 911.

After he was arrested again, an officer obtained an emergency protective order against him. A medic treated the woman for redness around her neck and injuries on her left side. Police entered nine pictures, the scarf and a written statement from the victim into evidence.

This time, the case was dismissed by the court, as indicated by a standard notation in the record: in the “interest of justice.”

Four months later, she told police that the man pushed her and she fell on a piece of furniture, hurting her neck and upper chest. The man kicked her out of his apartment, so she went to a shelter again. A counselor later sent her to St. Francis Hospital, where she was put on suicide watch.

Though he denied pushing or hitting her, the man was arrested for violating the restraining order.

The district attorney declined to prosecute the case, citing a lack of evidence, Donlan said.

Bastian, from the District Attorney’s Office, would not comment on any of these incidents. He said he did not have access to the prosecutors’ closed files, which contained more details about the legal case, because they were stored in a remote facility.

A Pivotal Murder Case

Part of the problem in addressing prosecution rates for domestic violence in San Francisco is that the record is incomplete. Gascón’s chief of staff, Cristine Soto DeBerry, said her office had no data on domestic violence prosecutions before July 2007, so it is uncertain whether the recent prosecution rate is anomalous compared with earlier periods, or with other jurisdictions over the long haul.

But the District Attorney’s Office says it is working to improve the handling of domestic violence cases, especially when victims are reluctant to speak up. To overcome obstacles to gathering evidence, it has provided training to first responders on collecting admissible statements and encouraging victim cooperation.

“They should assume from day one that the victim will not want to participate later on,” said Nancy Lemon, a professor at UC Berkeley’s Boalt School of Law and author of the text “Domestic Violence Law.” She called this practice “evidence-based prosecution.”

San Francisco’s no-drop policy emerged in response to the highly publicized homicide of a woman named Claire Joyce Tempongko in October 2000. The killing followed multiple domestic violence incidents in which the criminal justice system was slow to act.

The episode led to an investigation by the City Attorney’s Office and a series of recommendations by the Department on the Status of Women aimed at eliminating gaps in the city’s response to domestic violence. These included increased tracking of cases across agencies and a Police Department policy mandating arrest after any domestic incident that turns physical.

Reformers also pushed through changes in education and social services. Police now hand a list of resources to victims who might need help after they leave the scene. Raising public awareness of the problem, advocates say, encourages victims to come forward before they are badly hurt.

San Francisco’s “no drop” approach is by no means novel. Similar policies have been in place since 1985, when the San Diego district attorney mandated pursuit of all domestic violence cases for which evidence was available, even without victim cooperation.

Defenders of the policy touted a subsequent decline in domestic violence-related homicides. Deborah Epstein, a professor at Georgetown University Law School, said domestic violence homicides fell in San Diego.

Higher Legal Hurdles

Bringing domestic violence cases to trial has become increasingly difficult for prosecutors across the country. In 2004, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Crawford v. Washington that a victim’s statement could not be used in court if the victim did not testify or submit to cross-examination.

In California, it’s been a mixed bag. One state Supreme Court ruling allows prosecutors to have expert witnesses testify if victims recant. Another permits the use of out-of-court statements if the witness is missing or dead.

But then in 2008, the Legislature voted to prohibit forced testimony from uncooperative victims.

San Francisco’s Department on the Status of Women’s 2010 “Comprehensive Report on Family Violence” cited recent changes in law as major challenges to gathering evidence for court. But the changes do little to explain why San Francisco’s prosecution rate is well below that of other counties in the region from 2007 to 2011.

Domestic violence remains a major public safety concern nationwide. A 2010 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that 71 million Americans had experienced intimate partner violence in their lifetimes, and 10 million experienced violence in the previous year.

Domestic violence “is a crime that we should not respond to with silence,” said Michelle Daniels, head deputy district attorney with the Family Violence Division in Los Angeles County. “It affects not only the lives of the victims, but also those who grew up in the household. The more people are educated, the better and safer our society will be.”

Research suggests that local authorities often know about abusers before they commit crimes that land them in jail. The Police Foundation, a Washington, D.C., policy group, found in one study that half of domestic violence assault cases followed at least five prior visits by the police to the same address.

“When domestic violence is ignored,” said Brian Namey, a spokesman for National Network to End Domestic Violence, “lives are literally on the line.”

Threshold For Prosecution

The tsunami of media coverage of the Mirkarimi saga, which stretched into the fall of 2012, sparked a debate about when it is appropriate to pursue prosecution without the cooperation of the victim. In late January, the San Francisco Chronicle prominently mentioned the “no drop” policy, though representatives from the District Attorney’s Office now seem to back off the term. Gascón himself was not quoted using it.

But with thousands of cases declined for prosecution in recent years, the city’s official policy appears to contain a few ambiguities.

Sometimes, if the evidence is iffy, it comes down to a judgment call.

Police reports are filled with details that, before they ever get to prosecutors, contain disturbing stories. But they may or may not end up considered pressing in court as crimes.

On Jan. 7, 2011, San Francisco police responding to a domestic violence report in the Taraval District found a woman with two black eyes and a swollen right cheek.

A neighbor had called police after the woman rang his doorbell and said she had been abused by her boyfriend, and did not know what to do. The police report said the boyfriend had injuries on his hands, suggesting he had attacked her.

The boyfriend’s father told police that he witnessed the couple physically fighting throughout the previous evening.

But the injured woman said she loved her boyfriend and did not want him to face charges.

The final disposition of this case? Court records show the district attorney declined to prosecute, citing a lack of evidence.

Ruth Tam and Jason Winshell of the Public Press, and Chase Davis of the Center for Investigative Reporting, contributed research to this report.

This story appeared as part of a special report on domestic violence in the Fall 2012 print edition of the San Francisco Public Press.