Plan would shrink smallest living spaces by one-third, but opponents fear crowding

San Francisco of the near future could be a place where thousands of young high-tech workers pack into 12-by-12-foot boxes in high-rises, each equipped with a combination desk/kitchen table, a single bed and the overall feel of a compact cruise ship cabin.

A developers’ group is pushing the idea that tiny apartments could be the answer to rising rental prices, and has convinced the Board of Supervisors to put the proposal up for a vote next Tuesday.

The plan is to reduce the minimum living space in apartments from the current 220 square feet to just 150 — a little larger than a standard San Francisco parking space.

Developers say they can house more people if they are able to pack more units in new buildings. They call these apartments “affordable by design.” Some activists are calling them “shoeboxes.”

“How small is too small?” asked Sara Shortt, executive director of the Housing Rights Committee, a San Francisco-based tenant rights organization. “There’s a slippery slope when it comes to habitability and quality-of-life issues.”

The move could lead to more residential development in a city where the vacancy rate is close to zero. But skeptics say that if private developers can squeeze more rent from each square foot, builders of affordable-housing could be priced out of the real estate market.

Last month, Supervisor Scott Wiener proposed the ordinance to amend the city’s building code. Housing rights advocates say they want more time to consider its potential effects on all aspects of housing policy.

Rising rental prices are squeezing San Franciscans’ pocketbooks. In June, average apartment rental rates were up 15 percent compared with the same month last year, according to Trulia, a real estate research firm. Wiener and supporters say the ordinance would alleviate pressure on the housing market, and reduce rents.

Neither side can say for sure how much of an effect this change would have on rental prices, though everyone’s got a theory.

Initially, at the June 12 meeting of the Board of Supervisors, activists expressed worry that the proposal would threaten to remove local rent control protection through a provision in the 1995 Costa-Hawkins Act. The state law allows landlords to bring rents to market rate after extensive renovation.

Wiener amended his bill to apply only to new buildings, alleviating fears that existing units could be chopped up and turned into “new” apartments exempt from rent control.

“We have been assured by Supervisor Wiener that the intention was never to jeopardize any rent control units or displace any tenants,” Shortt said.

Is all construction good?

Wiener said his ordinance would increase the housing stock quickly, at a time when the city is working within a regional push for “smart growth” — transit-friendly urban housing that reduces the economic demand for suburban sprawl. (See the Public Press special report from the Summer 2012 print edition: Growing Smarter: Planning for a Bay Area of 9 Million.)

“We have a housing shortage in San Francisco,” Wiener said. “It’s a densely populated city where a lot of people want to come, and we have to add to our housing supply in a smart way.”

The idea for Wiener’s legislation came from a group called the San Francisco Housing Action Coalition, an odd assemblage of private developers, large landowners and civic organizations. More than half of its 75 organizational members are real-estate companies, private developers, development lobbyists or architecture firms. But it has a few civic organizations, such as the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition, Habitat for Humanity and Greenbelt Alliance.

The group says it advocates “the creation of well-designed, well-located housing, at all levels of affordability.”

Tim Colen, the Housing Action Coalition’s executive director, said the push to shrink apartments citywide came in a “backdoor sort of way.” The original impetus was to allow for the construction of smaller dorm rooms for students.

Colen said the citywide small-apartment ordinance would help San Francisco meet the smart-growth goals of the Association of Bay Area Governments. The regional planning agency has allocated 31,193 housing units to be built in San Francisco by 2014 to keep up with population predictions. But the city has fallen short of the needed pace of construction. The city’s Planning Department reported a net gain of only 269 housing units in 2011.

For Patrick Kennedy, owner of the Berkeley-based development firm Panoramic Interests, and member of the Housing Action Coalition, this legislation would address the housing needs of young tech workers, often blamed for the overheating rental market. Kennedy, who is also an architect, presented a scale model of his “affordable by design” apartments to the Planning Commission, and said these prototype micro-apartments could alleviate the price pressure on rentals. He claimed these units would divert single renters away from the market for larger family sized units, a process he calls the “cannibalization of family housing.”

“There’s always going to be two to three young techies who can pay more than your average family,” Kennedy said. “When tech workers can’t find housing, they bid up the housing for everyone else.”

But not everyone is convinced that allowing small single-person efficiency apartments would relieve pressure on the existing supply of family housing.

Gail Gilman, executive director of the nonprofit developer Community Housing Partnership, was skeptical of that narrative. She would only go so far as to say that it “anecdotally” made sense: “If you create a housing stock specifically targeting a certain segment of San Francisco’s population, that’s younger tech workers who are coming to the city, you’d free up other stock they were previously renting.”

But Gilman said for-profit developers want to build smaller units mostly because it’s good for their business. Multifamily housing is less lucrative because there are fewer families that can afford to pay for large apartments at the rates landowners would like to charge per square foot.

“I think that’s why for-profit developers prefer smaller units with higher density,” Gilman said. “They have more of a return on their investment that way.”

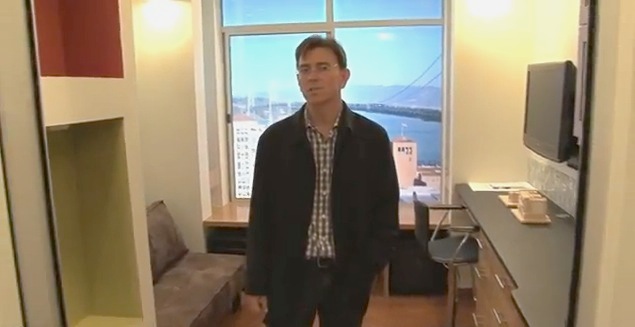

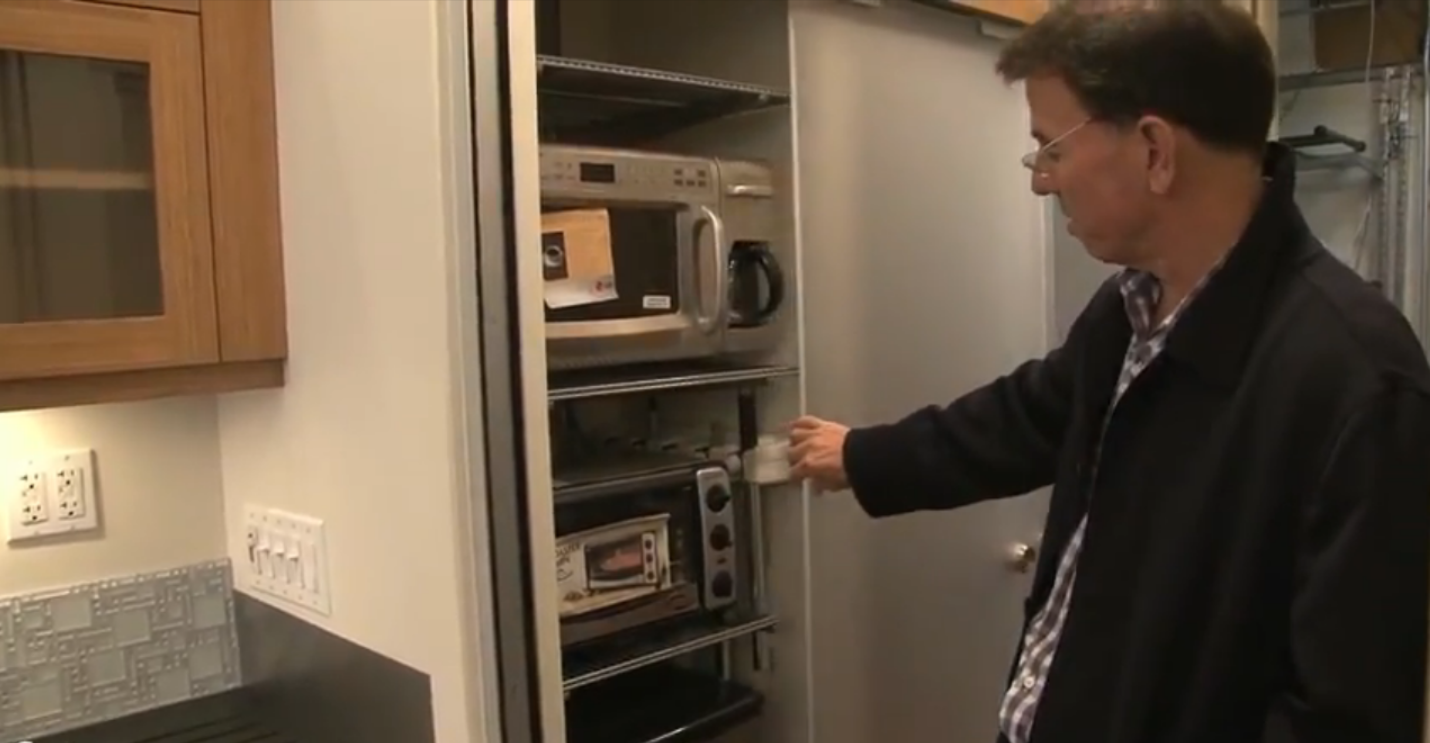

Kennedy built a prototype model unit with just 160 square feet of living space in a Berkeley warehouse. He said it was the smallest legal studio apartment that could be built in California, though it is currently banned in San Francisco. On the wall: a window plastered with a photo reproduction of a million-dollar Bay Bridge view. The room features a dining room table that converts into a guest bed, a master bed that becomes a couch and a shower that drains to the floor one foot from the toilet.

“Someone asked Aristotle Onassis, what was your secret to being rich? And he said two things: Always have a suntan and always have an address in the best part of town, even if it’s a broom closet,” Kennedy said in a video produced by Faircompanies.com, a video blog about sustainable technology. “Now I’m providing the broom closets in the South of Market area, metaphorically speaking.”

One room for a family

In response to objections that tiny dwellings might become the only housing that families or housemates could afford, exacerbating the problem of overcrowding, the legislation caps the number of occupants in an efficiency apartment at two residents.

“We right now have a very large number of efficiency-type units that have three, four, five people living in it,” said Paul Wermer, a sustainability consultant who spoke before the Planning Commission at a hearing last week. “That’s a lot of people in a small space, but that’s the reality.”

The two-person occupancy cap is unlikely to have much sway with critics. Shortly after Wermer spoke, Gwyneth Borden, a member of the Planning Commission observed that it would be virtually impossible to enforce the two-person limit. Low-income families who previously squeezed into efficiency apartments of 250 to 300 square feet might now be forced to occupy units half that size. With no ability to enforce the building code, multigenerational families might end up pooling their resources and living in much smaller quarters than ever, with hardly enough room to sleep.

“I have the ability to make the trade-off between a lower rent and a spacious apartment,” said Shortt of the Housing Rights Committee. “But if it becomes a basic overall lowering of standards for the market as a whole, then what we will start to see is units marketed to other income brackets that aren’t necessarily fit for people to be forced to live in.”

Sitting on the marble steps of City Hall, Sue Hestor, a land-use attorney, described how the surrounding Mid-Market neighborhood flipped from the lowest end of the rental market to the highest in less than six months.

“San Francisco is right now going through a mini-boomlet because of right here, right there, right there,” Hestor said, pointing to buildings within view of the Civic Center.

What exactly was she pointing at? “The Twitterati,” she said.

For Hestor, this legislation will, above all else, increase land values. In a free market, the ability to extract more profit per square foot produces a bidding war for real estate.

“The competition to build affordable housing is up to the land values,” she said. “If nonprofit developers are competing with Patrick Kennedy for the same lot, and the affordable housing community doesn’t have those profit margins built in, the developer can always pay more.”

Planning Commission staff reported that the legislation would enable builders to increase occupancy by 10 percent in a typical building that mixes efficiency and two-bedroom apartments. If they wanted to construct new single-room-occupancy hotels, the building’s population could increase by 32 percent.

A position paper from the Housing Action Coalition, submitted by Wiener along with the legislation, notes that other large West Coast cities, including San Jose, Seattle and Santa Barbara, already allow for 150-square-foot apartments. Those cities were motivated by the need to house students, formerly homeless people and “low income and special needs” residents.

But Kennedy and Colen said the most likely market for San Francisco would be the technology workers who have flooded the city in the last two years seeking high-paying jobs in an expanding sector.

Hestor sees a private agenda at work: “Patrick Kennedy has a model, and he builds housing, and he makes a lot of money doing it, and he wants to do it. And so they will approve his units.”

‘Not enough voices’

On Tuesday, the issue goes back to the Board of Supervisors, which on June 12 punted the issue to the Planning Commission for further study. At the behest of housing-rights activists, Supervisor Christina Olague argued that more information was needed about the effects of the plan on the housing market and quality of life.

Activists say they were blindsided by the quick introduction of the small-apartment measure, causing them to scramble to do research and ask constituents for their opinions.

“It hasn’t been adequately studied, and not enough voices have chimed in on the discussion,” Shortt said. “I think it’s something that warrants a whole lot more debate than what has happened so far.”

For Wiener, the legislation will primarily support the development of new housing for a diverse swath of city residents.

“When you look at the demographics of San Francisco, we have a lot of families, and we also have a very large population of people who live alone,” he said. “This amendment will give us more flexibility to create housing for single people primarily, for seniors, for students, for troubled youth and for others who either don’t need a lot of space or can’t afford a lot of space.”

Gilman is supporting a November ballot measure proposed by Mayor Ed Lee called the housing trust fund, which would provide up to $20 million to 50 million for affordable housing development over 30 years. She said she hoped the primary beneficiaries would be homeless families and people in need of supportive housing services. She said the need for these types of housing has increased in the last three years due to the Great Recession.

But for Gilman and other nonprofit developers, building affordable family housing is no easy task. It takes three to five years to move a development from conception to rental. “Unfortunately,” she said, “there’s not that much in the pipeline.”

Supervisor Scott Wiener’s legislation to change the definition of efficiency units is scheduled for a vote of the full Board of Supervisors Tuesday.