Special victims unit to take a new victim-centered approach to human rights violations

The little-noticed use of San Francisco’s human trafficking task force to arrest street prostitutes over the summer underscores a sharp nationwide debate on how local law enforcement can help rescue victims of economic and sexual slavery.

Until October, the city’s anti-trafficking team operated out of the San Francisco Police Department’s vice crimes unit. With the help of a federal-state grant, the team racked up more than 15 investigations of suspected traffickers. But in the spring it altered its tactics, making large-scale arrests of dozens of prostitutes in the Polk Gulch neighborhood, in response to complaints from neighbors.

While 60 percent of the prostitutes were “assessed” for evidence of human trafficking, according to arrest reports, the operations otherwise looked like typical street sweeps in problem areas leading to misdemeanor charges, said experts inside and out of the department. One victim was identified and referred to a social service agency, while several suspected victims did not come forward, and were booked.

The vice crimes unit’s tactics have vacillated in the last year as high turnover of anti-trafficking team leadership slowed investigative progress. Last April, less than a year into the grant, the department told the state it would prefer to use the money to perform “aggressive street enforcement of a more general nature.”

The original grant, federal funds awarded by the California Emergency Management Agency, was initially intended for undercover human trafficking investigations and permit inquiries into suspect businesses.

But in an email correspondence and phone conversations, the state grant administrator quickly approved the change. Then, in May and June, the police conducted a sweep of at least 41 prostitutes.

In October the department announced it was shifting the human trafficking work to a newly overhauled special victims unit. Police officials repeatedly said the new office, which is to include more than 50 investigators, at least three of whom will specialize in human trafficking, would put renewed focus in that area.

The reorganization came just before the department was to hear whether the San Francisco police and a local victim service provider, Asian Pacific Islander Legal Outreach, would each receive federal grants totaling $500,000 over two years from the Bureau of Justice Assistance and Office of Victims of Crime.

But the move did not come in time. The San Francisco Police Department was not awarded the grant. Instead it was awarded on Oct. 1 to the San Jose Police Department. The primary reason given for the denial was insufficient description of how the police would work with their nonprofit partner.

Although grant evaluators considered the department’s proposal comprehensive, one wrote that the human trafficking investigations were run out the vice crimes unit at the time that the application was filed.

This runs counter to a recent federal directive requiring that future grants no longer be run out of vice units — and that they pay equal attention to the wider problem of labor trafficking beyond cases of sexual exploitation.

Victim centered

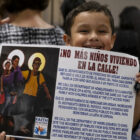

Some criminal justice experts say San Francisco’s recent approach of finding victims through arrests runs counter to rescue and support for victims and catching traffickers.

Identifying human trafficking victims by arresting street prostitutes “just drives them underground,” said Dina Haynes, a professor at New England Law in Boston. Haynes, who does yearly human trafficking training for more than 5,000 members of the Department of Justice and Homeland Security, also said that victims who are undocumented immigrants risk deportation by talking to police.

U.S. officials also warn against looking for victims of sex trafficking through arrests. The federal government’s human trafficking training materials for local enforcement warn that “victims will have been coached to anticipate the arrival of attorneys, and their cooperation with law enforcement may be delayed or nonexistent. In other instances, trafficker accomplices who are known to the victim may be posing as victims.”

The San Francisco Police Department’s own human trafficking expert, Sgt. Arlin Vanderbilt, said he thought the operation had not been the best use of department resources.

“If your objective is to primarily identify human trafficking victims and address their needs, contacting them through the arrest process is the least effective way of doing it,” Vanderbilt said. “It’s counterproductive.”

Vanderbilt was the lead investigator on the team at the time of the prostitution sweep. He said he transferred to other duties in the department over concerns about the change in the anti-trafficking team’s approach.

“I wasn’t happy with the direction that the vice crimes unit was going,” he said. “I didn’t feel that there was a strong enough support for investigations.”

Change in state grant

Capt. Antonio Parra, commander of the newly reconstituted special victims unit, defended the use of state Emergency Management Agency grant funds for the sweeps on and around Polk Street. Staff racked up more than 350 hours of overtime to conduct at least nine sweeps between mid-May and the end of June, according to a quarterly report to state officials. Based on billable overtime rates in the original grant request, this would total more than $29,700.

“This change in direction and enforcement to the street level was proposed to Cal EMA and it was approved through the proper process,” he said.

Tina Walker, a spokeswoman for the agency, said the Police Department’s use of funds was consistent with the spirit of the grant. She said local law enforcement has the discretion to use funds to address changing local needs.

San Francisco Police Lt. Jason Fox, now leader of the human trafficking task force, concurred with Vanderbilt that finding human trafficking victims by arresting them was ineffective, but with qualifications: “I think on its face I agree with him. But it certainly has its place. It certainly is an instrument in which we can contact potential victims through the arrest procedures as they commit crimes or as they are being victimized.”

Beyond sex cases

The vice crimes unit made some progress in sex trafficking cases using the state grant. In 2010 it referred nine sex trafficking cases to the District Attorney’s Office for prosecution. One suspected trafficker was criminally charged. In the first quarter of this year, six cases have been referred to prosecutors, and three have been charged.

Most of these cases involved investigating sex trafficking. Cindy Liou, staff attorney Asian Pacific Islander Legal Outreach, the leading local service provider for trafficking victims, said the problem of human trafficking, however, is even bigger than sex abuse, and so far the police have made little progress in this area.

“The vast majority of our cases in the last three years have been labor cases,” she said.

As of mid-September the police had not referred any labor trafficking cases to the District Attorney’s Office during the calendar year.

Police Chief Greg Suhr said he now wants the department to move beyond sex trafficking and prostitution investigations.

Fox explained the rationale: “Prostitution is a very high-profile part of human trafficking. It’s one that’s very tangible. People understand sex and all of that plays into it. It’s a lot bigger than that. And the chief wants our enforcement to be a lot bigger than that.”

Federal changes

This year, federal authorities are working to get local law enforcement agencies to abandon their practice of using vice crimes units to address human trafficking. Haynes and Homeland Security Investigations officials both said officers with sex crimes training may lack the expertise to recognize and investigate other human rights violations, including labor trafficking.

Since 2004 the federal Bureau of Justice Assistance and the Office of Victims of Crime have funded 42 human trafficking task forces within law enforcement agencies.

Last year the Bureau of Justice Assistance undertook a comprehensive review of the grant process, looking at past performance and comments from law enforcement and victim-support nonprofits.

The review led to the creation of a new “Enhanced Collaborative Model to Combat Human Trafficking,” which requires funded agencies collaborate with federal agencies and focus on both sex and labor trafficking.

Although the police department will not be able to count on the Bureau of Justice Assistance grant, human trafficking will remain a priority.

“We don’t need this money to do the right thing,” Fox said. “The chief is going to reprioritize how he spends the money. His management priorities are to make sure that human trafficking is staffed to the level that he believes is sufficient to raise awareness, combat the problem, and help the prosecutions.”

Vanderbilt said the department will move forward with intensive human trafficking investigations and abandon its past emphasis on unproductive enforcement activities such as arresting pimps and prostitutes.

He said that for the remainder of the California Emergency Management grant, which expires in September 2012, human trafficking investigations will take a victim-centered approach and adhere to the spirit of the department’s original grant proposal.