Update: The Board of Supervisors unanimously passed the shelter access legislation on June 8 and Mayor Gavin Newsom signed it on June 24. The legislation will be enacted on July 24.

San Francisco’s adult homeless shelter system is seeing fresh attempts at reform on two fronts: one through the settlement of a lawsuit, the other through new legislation.

Since July 2004, more than 400 shelter beds have been eliminated, and the lawsuit settlement between the city of San Francisco and the Western Regional Advocacy Project will spare further reduction from budget cuts for this fiscal year.

In addition, per legislation sponsored by Supervisor Eric Mar, staff members of cityfunded shelters will receive training in disability issues in compliance with the Americans With Disabilities Act. Mar’s proposal would amend the Standards of Care law, which the Board of Supervisors enacted in 2008.

The original act established minimum standards in shelter conditions, including comfort and cleanliness of facilities and mandated professionalism by staff, as well as a grievance procedure for homeless clients who are denied services.

"I believe that with these new measures in place, homeless people will have greater access to basic human needs, safer and cleaner places to stay," Mar said in a statement.

The legislation would also simplify the process of renewing shelter reservations, lengthen stays to a maximum of 141 days, allow 24-hour access to beds, and provide information about shelter rules and how to access case management services.

The Shelter Monitoring Committee, which oversees shelter conditions, would be authorized to investigate contractual violations and refusal of beds to clients.

If approved, the legislation could take effect as early as mid-July, according to Cassandra Costello, Mar’s legislative aide.

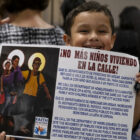

Mar agreed to sponsor the bill after he was approached by the Coalition on Homelessness, a Tenderloin-based advocacy group, which had published a report in 2009 on the delays homeless people encountered in making seven-day reservations for beds. Coalition director Jennifer Friedenbach described the process during a May 20 hearing as “not a homeless person-centered process,” but a “system-centered process.”

The push for the “person-centered process” was also behind the lawsuit by WRAP, an alliance of organizations serving the homeless. The suit was filed in August of 2008 and reached a settlement this April. According to the deal with the city, homeless clients must be accommodated at any shelter for which they have proof of a reservation, even if it does not appear in the reservation system.

The suit, along with Mar’s legislation, seeks to redress scenes such as those described by David Harness, a former ship repairman who is now homeless after losing employment due to disability.

He testified that people sometimes literally fight for a bed. "My reservation ran out and I was attacked in front of Glide Church, waiting for a reservation," Harness said, adding that someone behind him took a swing at him to take his place in line.

"They had to put me in a police car and take me to another location for my own protection," he said.

But Tomas Picariello, a former shelter occupant, said he was skeptical about amending the standards. He said he doesn’t believe the Department of Public Health adequately enforces the current rules.

"It’s creating false hopes for shelter residents," Picariello said.

SUIT ‘PRESERVES STATUS QUO’

WRAP’s suit directly addresses the reduction of beds for homeless people.

"The only way we were getting them to stop cutting is this case," said Paul Boden, WRAP’s executive director. "The bottom line is it preserves the status quo in terms of capacity."

The suit’s core issue was an allegation that the shelter system favored people enrolled in the welfare program known as Care Not Cash. Beds in the system are disproportionately allotted to Care Not Cash recipients and for longer periods of time, according to the lawsuit.

Co-plaintiff Calvin Davis had exactly that problem in his 10 years of homelessness in San Francisco.

Now 60 and living in public housing, the former contract painter and car detailer often spent fruitless hours waiting for shelter. He went on Supplemental Security Income after his legs and shoulders failed to heal properly from an injury and he could no longer work.

By his estimates, Davis was turned away at least eight times a week because the only empty beds were held for Care Not Cash. Davis had to reserve his bed repeatedly and make curfew each night or risk losing his bed. However, his Care Not Cash counterparts were guaranteed a bed for 45 days, whether or not they used it.

"A lot of them beds are empty for people," Davis said. "You don’t have to come in every day if they’re open" to Care Not Cash recipients.

Figures from the Human Services Agency’s statistical report on Care Not Cash show 563 active homeless clients in January 2009. That month, the city counted 5,614 indigent in their biennial application for federal funding. By those estimates, one in 10 homeless people are on general assistance. Yet out of 1,213 beds available in February, 378 — or about one in three — were expressly reserved for Care Not Cash in three of the city’s largest shelters.

Indigent people must prove a lack of income or assets to qualify. Since Care Not Cash took effect in 2005, welfare payments were reduced from $395 per month to $59 with provision of services.

L.J. Cirilo, a shelter client advocate, had to apply for welfare to avoid repeated waits. Her case manager suggested it was the best way of keeping a bed during her six months of homelessness, she said.

"Stability is the No. 1 thing a homeless person needs," Cirilo told the Rules Committee. "A person who has been on the streets is going to need time" to find housing.

A version of this article was published in the summer 2010 pilot edition of the San Francisco Public Press newspaper. Read select stories online, or buy a copy. CORRECTION 7/30/10: A previous version of this story misspelled L.J. Cirilo's last name.