By Lizzy Tomei

The Public Press

Part of the community-funded City Budget Watchdog series

|

| Joanie Marguardt (left) and Meshá Mongé-Irizarry (center) protest the impending closure of Southeast Mission Geriatric Services. The Department of Public Health plans to relocate the center’s program to a facility on Ocean Avenue. Photo by Monica Jensen/The Public Press. |

The impending closure of a 25-year-old Mission Street mental health clinic will force its clients to travel two and a half miles to seek essential services.

The change has frustrated advocates for the elderly and health care workers, who say the city’s decision to consolidate services with another center on the western side of the city doesn’t do much to help balance the city’s budget but is a major disruption for hundreds of physically and mentally vulnerable adults.

Southeast Mission Geriatric Services’ programs will relocate from southern Mission Street to the OMI Family Center on Ocean Avenue, the Department of Public Health confirmed in a Friday statement. The move, proposed earlier this summer as part of city budget negotiations, comes despite the Board of Supervisors’ recent restoration of funding, which some supervisors intended to keep facilities like Southeast Mission Geriatric Services open.

The center, which provides psychiatric care and case management to mostly low-income older adults from the Mission, Bayview Hunter’s Point, Bernal Heights and other neighborhoods, is one of several social service programs in San Francisco shuffled by budgetary restructuring and cuts. In the case of Southeast Mission Geriatric, the health department says consolidating office space will preserve funding for services.

Southeast Mission Geriatric Services Part 2 from Monica Jensen on Vimeo.

But while Southeast Mission Geriatric’s program of care for older adults will continue to operate after it moves to the Ocean Avenue facility, clients and clinic staff have said the move will threaten access to treatment and disrupt patients’ daily lives. In addition to coping with mental illness, many of the center’s clients have physical illnesses and limited mobility. Seeking care at the new facility will mean a longer and unfamiliar commute for many.

|

| Southeast Mission Geriatric Services and the Department of Public Health dispute the number of clients who are served by the mental health clinic. Photo by Monica Jensen/The Public Press. |

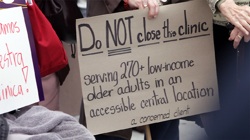

On Friday, carrying signs handwritten in English and Spanish, clients and other supporters gathered in front of Southeast Mission Geriatric to demand that mental health services for seniors remain in the neighborhood. Joanie Marguardt, a 61-year-old client, held a sign that read: "Do NOT close this clinic serving 270+ low-income older adults in an accessible central location."

Since the center’s closure was first proposed, the Department of Public Health has been careful to point out that its program was not being cut, just relocated. But given the supervisors’ recent restoration of millions of dollars in funding for social services and community programs, some protesters were baffled by the department’s decision to shutter the clinic.

“I’m really no longer trying to see the rationale in what they do,” said Pamela Fischer, a member of the board of directors of NAMI San Francisco, an affiliate of the National Alliance for Mental Illness.

“It seems very arbitrary,” she said. “This doesn’t strike me as being reasonable.”

District 5 Supervisor Ross Mirkarimi, who attended the protest along with fellow supervisors Chris Daly and David Campos, said the center is one of several casualties of the "policy ping-pong match" over the budget at City Hall. He also spoke of a worrying trend of "creeping privatization and consolidation of services" under the administration of Mayor Gavin Newsom.

In a statement Friday, the health department defended the relocation, noting that it planned to provide taxi vouchers for clients with difficulty accessing the new site.

“Given a choice, we prioritize money for services, not to pay rent,” Bob Cabaj, the director of community behavioral health services, was quoted as saying in the statement. “Relocating this small team to the same office as another mental health team enables us to preserve services.”

The health department also acknowledged that the transition would be difficult for clients and staff.

|

| “How are they going to get there when they live right around here?” said Margaret Moore, a client. Photo by Lizzy Tomei/The Public Press. |

“We have never experienced a relocation that did not initially upset some of the people involved,” Cabaj said. “Yet, we also see that three months after the relocation, people rarely remember the issue.”

The department also noted that most of the services provided by Southeast Mission Geriatric are housecalls, so most clients would not notice the relocation.

But the center’s staff and Department of Public Health officials disagree about the extent of the center’s services. When the closure was first proposed in June, the health department and Southeast Mission Geriatric provided significantly different numbers for the center’s caseload. Staff said they served more than 270 clients, while the department identified a caseload of 187. Both counts grouped home and on-site services together.

Health department officials with details of the closure could not be reached for comment Friday. But Dino Diodati, the contractor who built the clinic more than two decades ago and has remained its landlord since, said that he had been told the space would be vacated by Aug. 8. Clinic staff expect to begin moving out of their offices next week.

Seeking alternatives to relocation, clinic staff recently identified other Mission social service groups in need of offices — or faced with relocation — that had agreed to share the clinic space and split rent costs. Diodati has also offered his tenants a 7 percent discount on their rent.

Diodati, who converted a former supermarket to build Southeast Mission Geriatric, has watched the center both expand and fight cuts for many years. “I put this clinic together a long time ago,” he said. “These guys are the front line.”

The availability of the program’s mental health services at another location after the shutdown is little consolation, he added. "That’s the reason why you have community clinics, to serve the local community.”

“How are they going to get there when they live right around here?” said Margaret Moore, 72, a Southeast Mission Geriatric client. “We have enough clients to keep this center open.”