As the coronavirus curve flattens and San Francisco contemplates lifting shelter-in-place orders, public health officials are building a workforce of contact tracers to prevent a surge of transmissions.

Using a new data-tracking tool, the contact tracers will reach out to individuals who have been exposed to COVID-19 to inform them of the risk, ask them to quarantine and offer clinical guidance. If successful, the program could dramatically affect the course of the pandemic in the Bay Area.

With a relatively low number of known COVID-19 cases compared with other cities, San Francisco seems uniquely positioned to take advantage of contact tracing and contain the spread of the virus that causes the illness. “There’s hope that we could potentially isolate a really high percentage of all contacts,” said Alex Coburn, a third-year medical student at the University of California, San Francisco, who is helping coordinate student contact tracers.

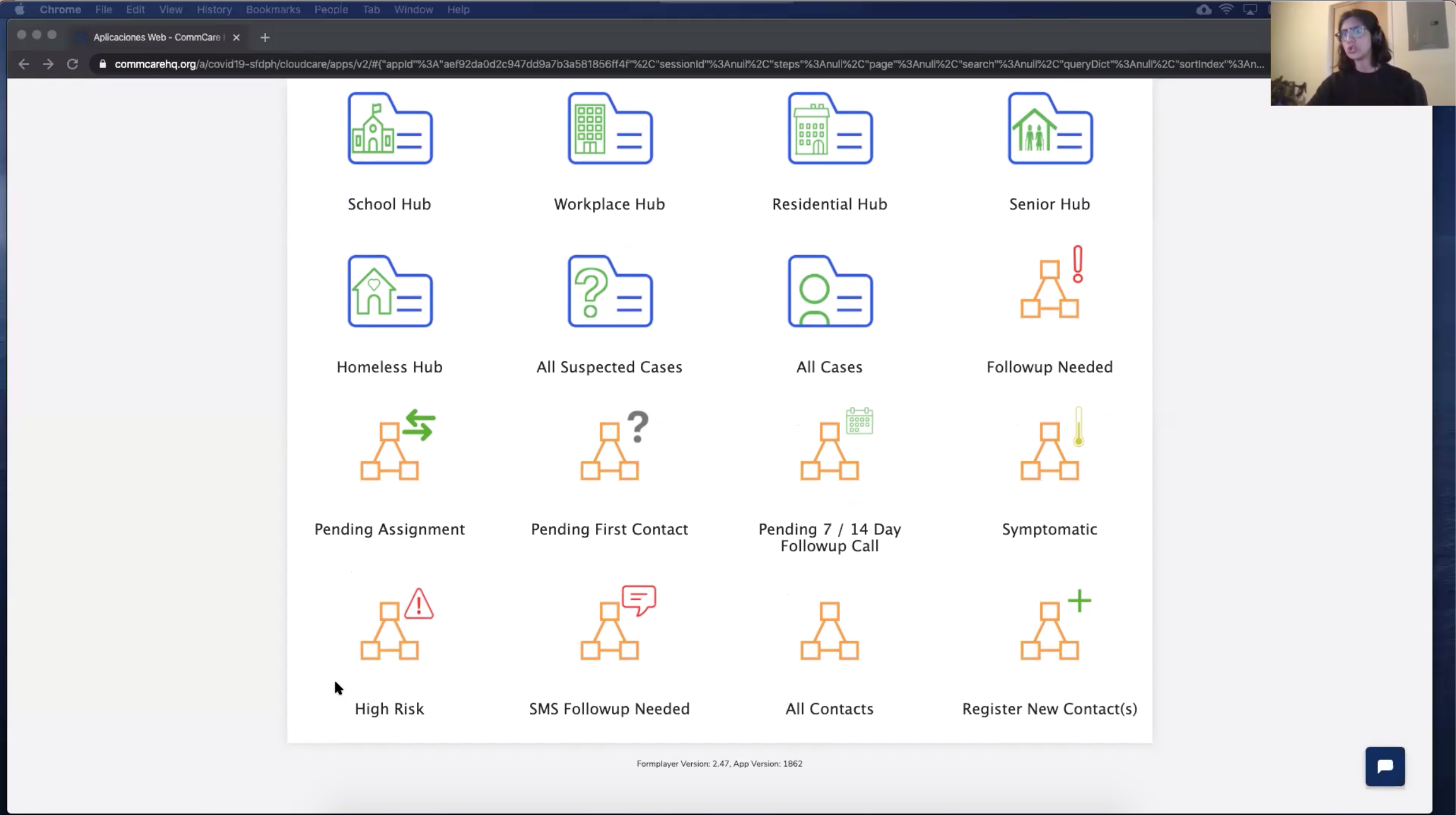

San Francisco’s contact tracing program is a partnership between the San Francisco Department of Public Health, UCSF and the Massachusetts-based software company Dimagi. Public health officials say Dimagi’s user-friendly platform will help them scale up a large workforce quickly. Trainings are already under way for a team of 140, which includes public health department staff members, city librarians, city attorney staffers and UCSF medical students. Dr. Grant Colfax, director of public health, said at a press conference last week that he hopes thousands across the region can eventually join the effort.

With 1,216 confirmed cases in San Francisco as of Monday, team members have their work cut out for them. “We want to do contact tracing for every single case in San Francisco,” said Dr. Mike Reid, an assistant professor at UCSF, who is involved with the program. “That’s the goal, and if we want to move beyond shelter-in-place, we have to have the capability that enables us to do that.”

In a demonstration last week, Dr. Reid and his colleagues explained how the process works. Using a specialized platform, team leaders assign cases to contact tracers, who first send a text, advising people that they will be receiving a call about a health matter. Over the phone, they inform people that they have been exposed to someone with a confirmed case of COVID-19, though they do not identify the individual. Then, prompted by the platform’s algorithm, they walk through a series of questions to assess the situation and determine a course of care. Team clinicians are also on hand to provide more specific medical information.

Overcoming language barriers

“One goal is to figure out who’s high risk and who’s not high risk for getting seriously ill,” said Coburn.

People who have been exposed to someone with COVID-19 will be asked to quarantine for 14 days. Contact tracers can connect them with services they might need to quarantine, including obtaining food and shelter. People can also choose to receive daily text messages or phone calls checking in on their symptoms.

Program leaders stress the importance of cultural sensitivity in these conversations. Contact tracers do not ask for immigration status, social security numbers or nationality, but they do ask for a preferred language.

In San Francisco, where the Latinx community has been disproportionately affected by the virus, coordinators like Coburn are trying to make sure that they have enough Spanish-speaking tracers. They also have access to interpreters through the public health department. Dr. Colfax said they are working to expand the program to include Cantonese, Mandarin and Tagalog.

Earning the trust of the communities most impacted by the disease will be crucial for the success of the contact tracing program. “We want to work with the community and we want the community to work with us,” said Susan Philip, director of disease prevention and control at the public health department. “It really does require the cooperation of everyone in the city who might be contacted as part of this effort.”

Coburn said the training he’s received at UCSF has put him in a good position to help. “Within the UCSF medical student community, there’s a lot of emphasis on cultural sensitivity and empathy and understanding,” he said. “We’re not trying to impose unwanted restrictions or requirements on patients. We’re trying to help get them the information they need and keep them and their families safe.” Coburn and his fellow UCSF students plan to start making calls this weekend.