Thousands of Salvadorans, Hondurans and Haitians await decision on Temporary Protected Status. Nicaraguans must leave in 2019 or face deportation.

Update Nov. 20, 2017: The Trump administration announced Monday that about 49,000 Haitians living under Temporary Protected Status must leave the United States by July 22, 2019. Acting Secretary of Homeland Security Elaine Duke “determined that those extraordinary but temporary conditions caused by the 2010 earthquake no longer exist,” the agency said in a news release.

Karen Pineda watches news reports of immigration raids on workplaces in and around San Francisco with increasing dread.

A single mother of two, she works as a maid in a downtown hotel and has had a temporary work permit for more than 17 years since she arrived in the United States from El Salvador after a devastating hurricane hit Central America. Pineda is among 320,00 people from the region and Haiti who came to the United States illegally but were granted temporary legal status because they had fled natural disasters, war or “other extraordinary and temporary conditions.”

Renewed by the Clinton, Bush and Obama administrations, Pineda’s permit may finally run out in the new year, a casualty of President Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown. If her protected status is not extended again, she and thousands like her in the Bay Area will be vulnerable to the same deportations as the people here without authorization she sees regularly on Spanish-language newscasts.

“They will eventually come after Salvadorans like me,” said the 42-year-old Pineda, whose name has been changed to protect her identity.

She and an estimated 195,000 other Salvadorans nationwide are the largest group with Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, as it’s commonly called, and face a March deadline for renewal. Roughly 50,000 of them live in California.

Driven Here by a Hurricane and Violence

Speaking by telephone from her home in Concord, Pineda described the tension she and others are feeling as they await the Trump administration’s decision. Last week, the Department of Homeland Security announced that 2,500 Nicaraguans who came to the United States in 1999 after Hurricane Mitch battered Central America will lose protected status. The Nicaraguan government did not request an extension.

The expiration date had been in early January, but the administration gave Nicaraguans an extra year, until Jan. 5, 2019, to leave. After that, without a change in their legal status they will be subject to deportation.

At the same time, Homeland Security said that a decision on 57,000 Hondurans whose permits were to expire Jan. 5, 2018, was extended six months “to obtain and assess supplemental information” on conditions in Honduras. About 6,000 live in California. In addition, nearly 50,000 Haitians who came after a ruinous earthquake in 2010 are waiting to hear whether their Jan. 18 expiration date will stand or be extended.

Pineda doesn’t have a good feeling about what lies ahead for Salvadorans.

“I’m not confident Trump will do the right thing” she said. “If he doesn’t, I’m going to have to make one of the biggest decisions of my life: Whether I stay without papers and risk being deported and separated from my children, or return to El Salvador, where it is extremely dangerous.

“I don’t know what I will do if they take away my TPS,” Pineda added. “My biggest concern is for my children. My boys are 12 and 8 years old. They were both born here and have never been to El Salvador, a country that is a disaster right now.”

Murder, Gangs, Sex Trafficking

The country has one of the highest murder rates in the world, and robbery, extortion, violence against girls and women, and sex trafficking are endemic. Gang violence has fueled a surge of unaccompanied children and families into the United States in recent years, and El Salvador’s economy depends heavily on remittances from expatriates. The safety and economic situation is similar in Honduras, where most of the nearly 2 million homes destroyed by Hurricane Mitch have not been rebuilt, while Haiti remains mired in food and housing shortages, decrepit infrastructure and a cholera epidemic since some Haitians were granted TPS after the 2010 earthquake that left hundreds of thousands dead.

Uncertainty has been the hallmark of the program, which was established by Congress in 1990 and has provided temporary legal status and protection from deportation to around 440,000 nationals from 13 countries.

Pineda and the others have qualified for temporary protected status by residing in the United States for at least 15 to 20 years and undergoing rigorous and regular vetting by immigration authorities. Each recipient has also paid tens of thousands of dollars in renewal fees, which are due every 12 to 16 months. Pineda said she has paid $75,000 since she arrived in 1999.

The Nicaragua announcement came on the heels of a letter from Secretary of State Rex Tillerson to acting Homeland Security Secretary Elaine Duke saying that conditions in Central America and Haiti no longer merited TPS protection, the Washington Post reported.

Central American activists in the Bay Area questioned that claim.

“What prospects do people have in their homelands?” asked Lariza Cuadra, executive director of CARECEN San Francisco, a Central American service and advocacy organization based in the Mission District. “None.”

‘People Are Starting to Worry’

Cuadra sees the rejection of TPS as just the latest of the president’s anti-immigrant policies, including building a Mexico border wall, banning citizens from several Muslim countries, adding 100,000 U.S. Border Patrol officers and allowing them to operate beyond 100 miles from the border. Her busy organization has served more than 15,000 TPS holders since 1990, and has started receiving calls from people concerned about their future. Some wonder whether they should go into hiding.

“People are starting to worry,” Cuadra said. “We are telling people to stay put until an announcement about their countries is made.”

Cuadra and CARECEN are also providing information and services to TPS holders who may qualify for an alternative path to legalization, specifically those with spouses or children who are U.S. citizens.

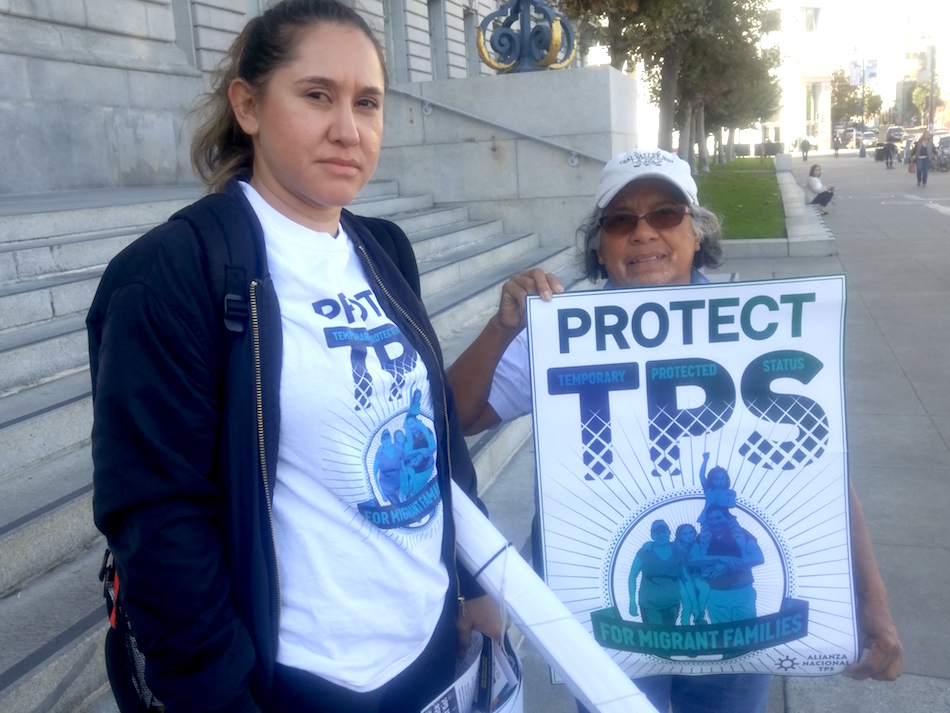

“I’m not thinking about ‘Plan B,’” Rina Valle, a 38-year-old Salvadoran TPS holder who works as a janitor in San Francisco, said last week at a rally on the steps of San Francisco City Hall. “I only have ‘Plan A’: fight. We don’t have a choice.”

Valle, who commutes daily from Hayward, stood alongside TPS holders from Haiti and Honduras and their supporters, all bearing the flags of their native countries and holding placards declaring, “Save TPS” The protest was organized by the Bay Area Coalition to Save TPS, a network of organizations that includes the African Advocacy Network, RENASE, Nicaragua Community Action and CARECEN.

Sitting in the home she owns, Pineda listened to news of protests and actions with enthusiasm.

“I’m glad they’re doing something to help our people,” she said.

Does she plan to join the protests? “Not right now. I need to prepare myself and my boys for whatever comes next, which will absolutely not include going to El Salvador.”

Pineda said she is “exploring” her options, which include selling her house and moving to another address or perhaps even another city where relatives live.

“What would I return to?” she asked. “El Salvador has no jobs, it never recovered from the war and is one of the most violent countries in the world. What is there to go back to? Nothing. I don’t have much here, but it is something. It is all that I have.”