From her office in the Mission District, Yanira Arias organizes immigrant communities throughout the United States, winning some campaigns, losing others. Through it all, she has known the day would come when she would be organizing to hold onto the life she has created in San Francisco. With the U.S. government’s blessing, she has been able to stay here since fleeing El Salvador after a series of deadly earthquakes in early 2001.

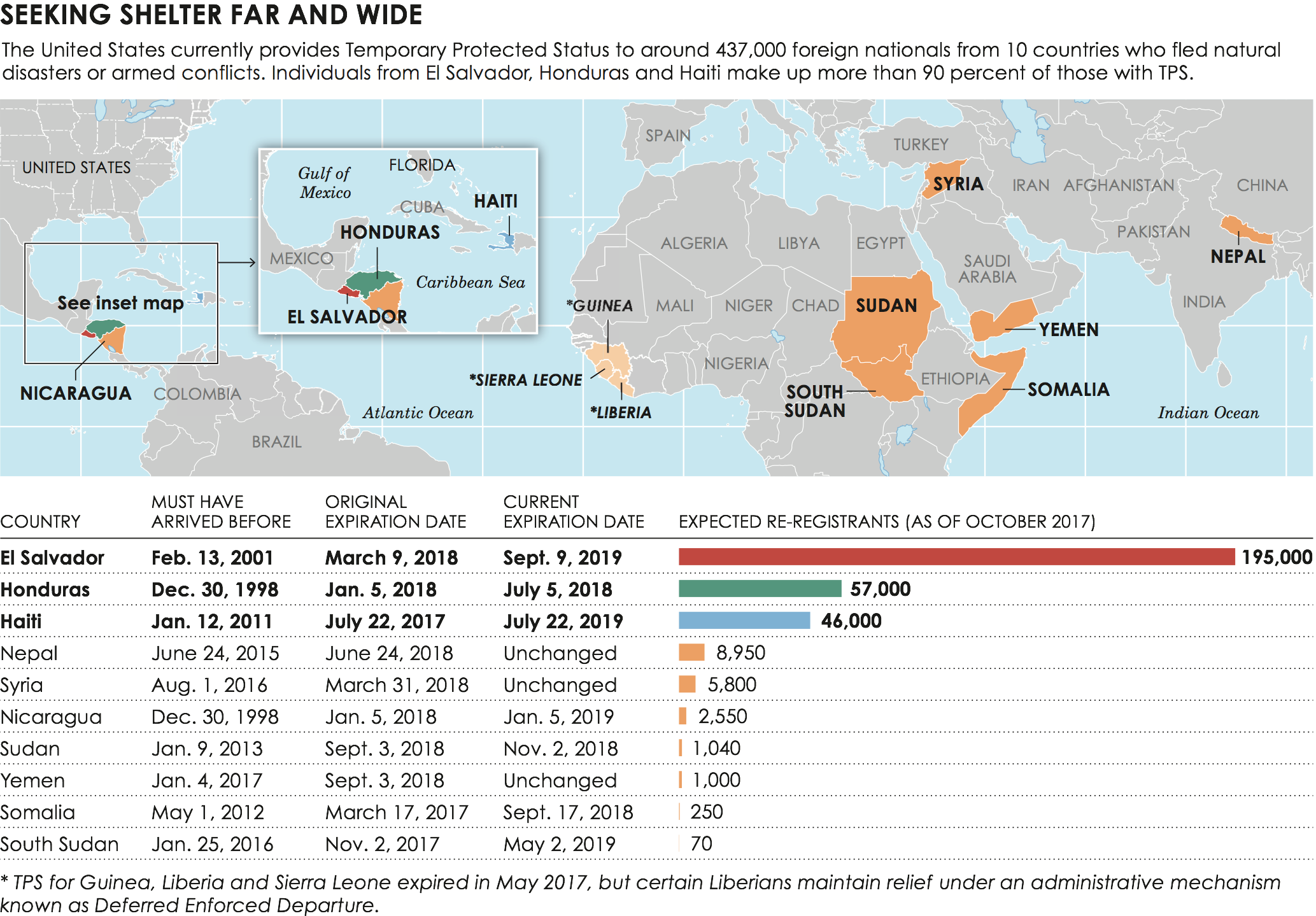

That day has arrived for Arias and more than 195,000 other Salvadoran immigrants and tens of thousands from the region who were granted temporary permission to live, work, raise families and buy homes after being driven from their homelands by natural disasters, civil war and gang violence. They are the latest immigrants whose fortunes have changed for the worse under President Donald Trump.

|

| Yanira Arias has lived and worked legally in the United States since earthquakes devastated parts of El Salvador in 2001. Photo by Garrick Wong // San Francisco Public Press |

In January, the administration announced that Salvadorans, as Nicaraguans and Haitians learned for themselves weeks earlier, would lose Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, forcing them to plan their departure from the country or become permanently legal by early 2019. Their predicament is shared by the so-called Dreamers, children brought into the country illegally who are fighting to remain since the president ended DACA, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals.

Three Choices, Different Futures

Without intervention by Congress, Arias and the others benefiting from TPS — which San Francisco activists helped birth in 1990 — face three choices that offer radically different futures: try to “adjust” their status through the immigration system to become permanent residents, return to homelands ravaged by poverty and violence, or join the millions of undocumented migrants already threatened with deportation. Advocates are turning to the courts for help.

“They’re getting ready to criminalize me,” said Arias, the national campaign manager in the Bay Area office of the immigrant-advocacy group Alianza Americas. “I’ve seen what they put people through in those awful detention centers. I have started imagining myself in those horrible places, because the fact is, that could be me. I may face a prolonged detention like so many others, but I will do whatever I can to avoid that.”

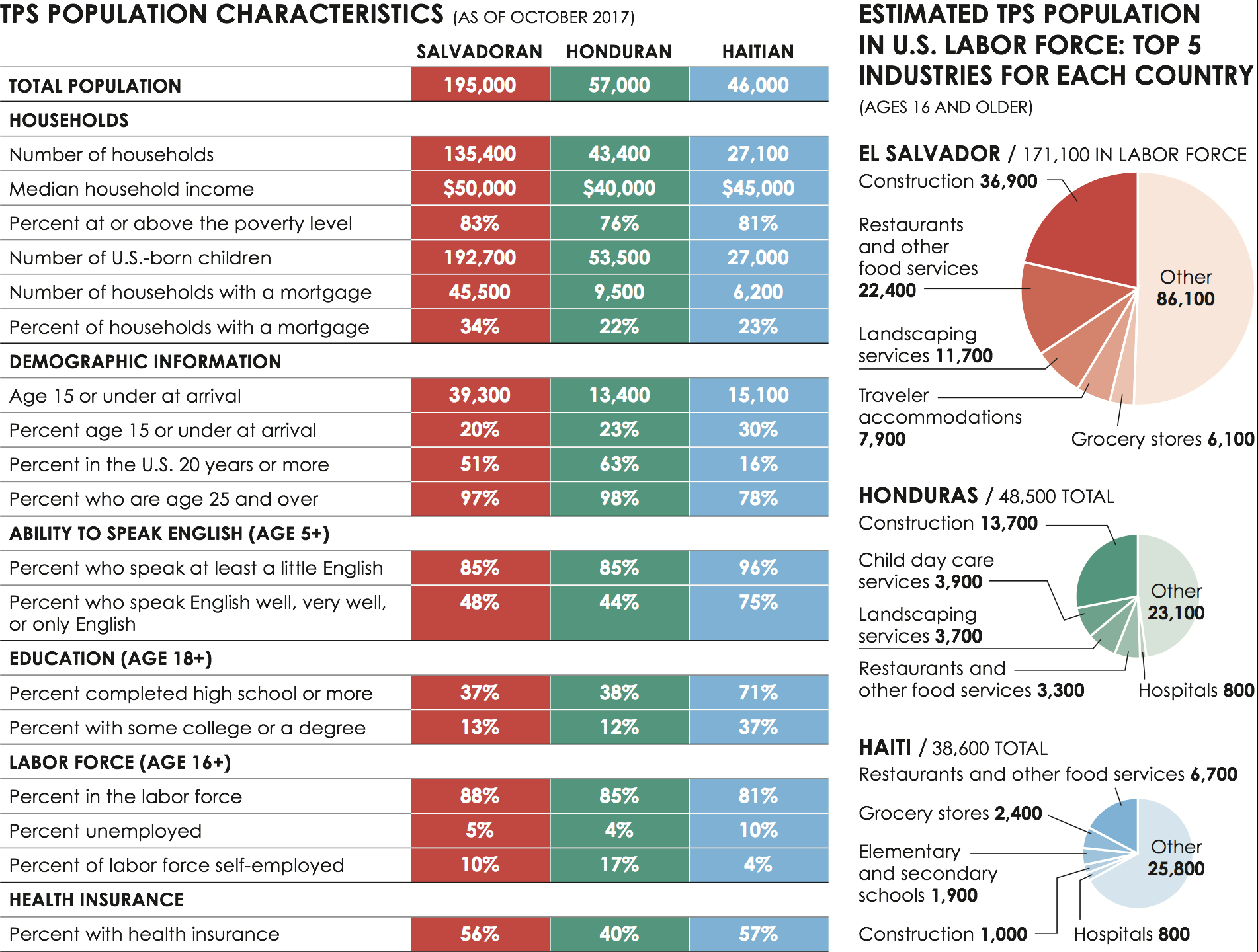

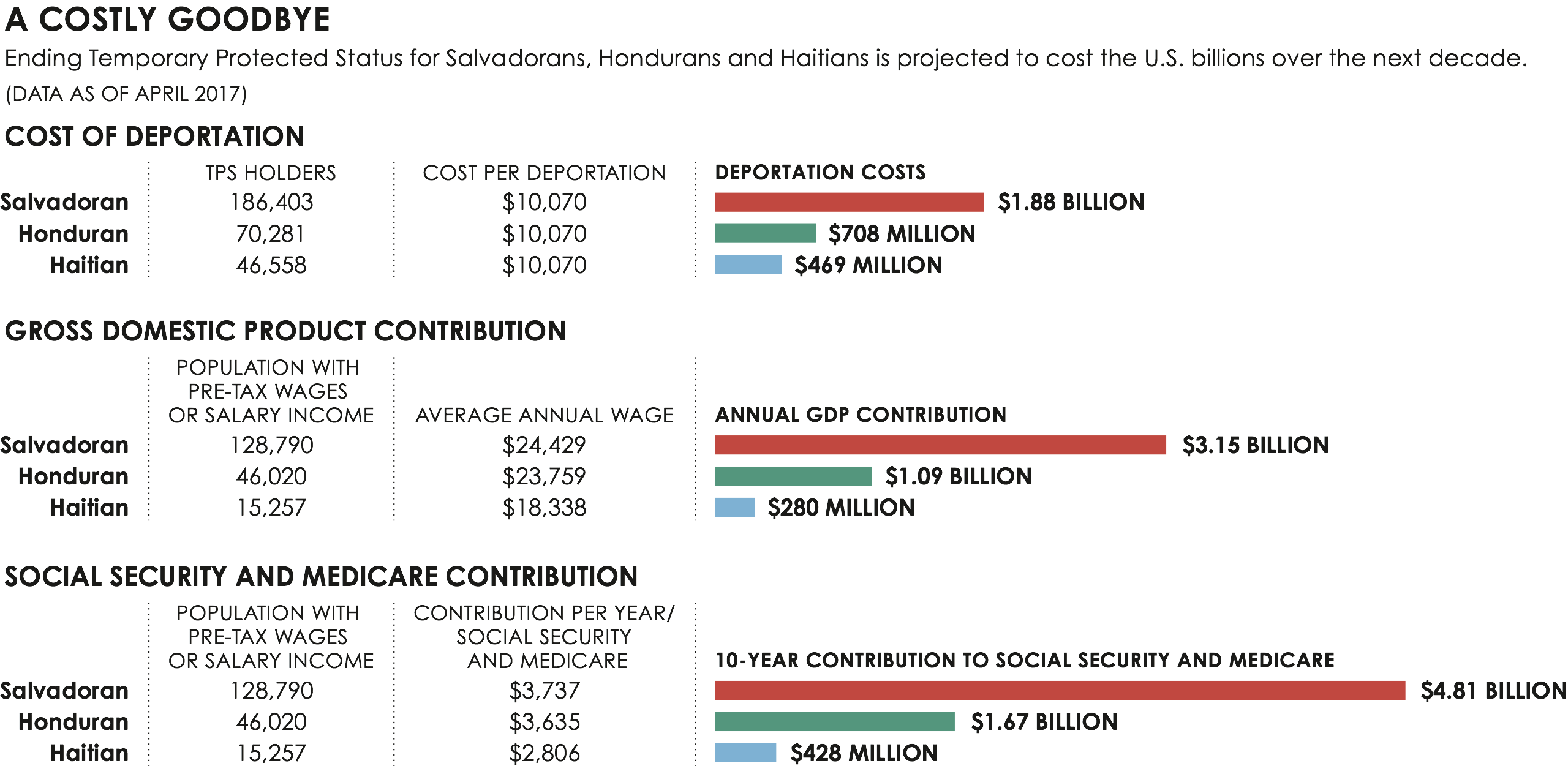

The effect of ending legal protection will be enormous for the Salvadorans and more than 120,000 Hondurans, Nicaraguans and Haitians who also have lost or may soon lose their legal status. But it extends beyond their personal upheaval, research shows:

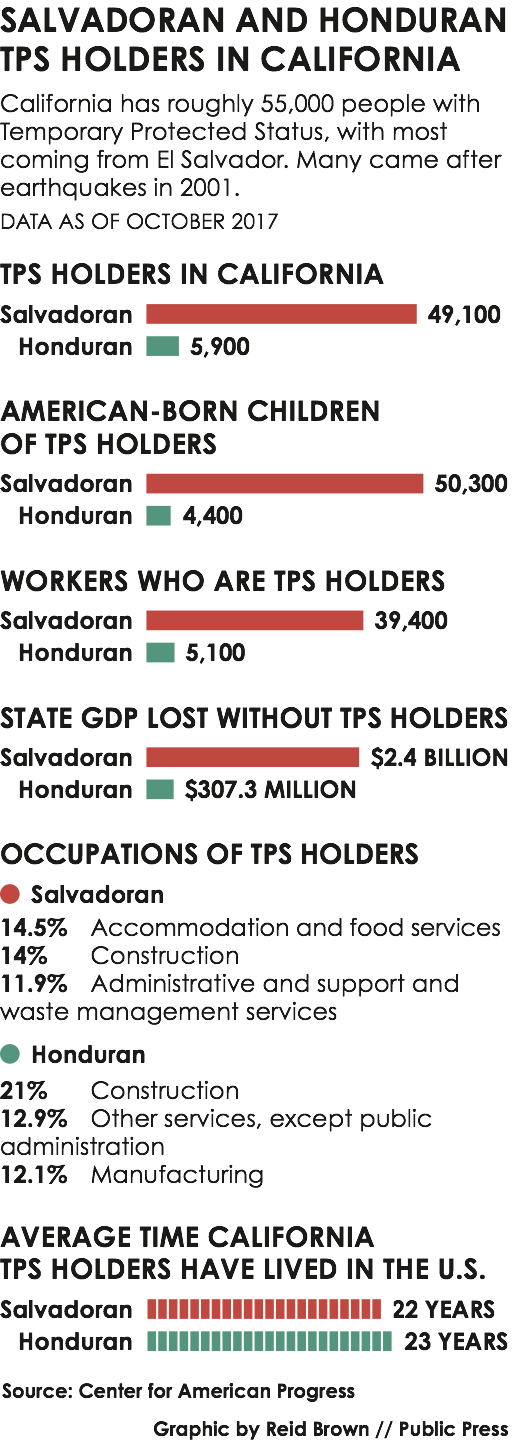

• In California, which has the most TPS recipients, the estimated 49,000 Salvadorans and 6,000 Hondurans with temporary status contribute more than $2.7 billion to the state’s economy. About a third are homeowners.

• Replacing trained workers could cost businesses an estimated $673 million nationwide. Construction and service industries would be most affected.

• Central America and Haiti would be hit hard economically, because they depend heavily on the billions of dollars immigrants send home. Remittances account for 17 percent of the economies of El Salvador and Honduras.

• Gang activity is predicted to increase in the United States and Latin America, including extortion, human smuggling, sex and drug trafficking, and document forgery. Security would further deteriorate in El Salvador and Honduras, where thousands of members of the notorious MS-13 and 18th Street gangs terrorize and control local populations.

To immigration opponents, none of that matters.

“It’s time for those who have benefited from their TPS status to return home,” said Dave Ray, communications director for the Federation for American Immigration Reform, in Washington, D.C. “The ‘T’ in TPS stands for ‘temporary.’ TPS was established to allow citizens of countries affected by some unforeseen event and were legally in the U.S. to remain here temporarily — until the triggering incident had passed.

“In each and every case under consideration the immediate crises have long since passed and, for the most part, the home countries are no worse off today than they were before the triggering event,” added Ray, whose organization works to end illegal immigration and sharply restrict legal immigration.

People in the United States without authorization also have been eligible for TPS.

Ray’s group does not have a centrist reputation in the immigration debate. It has been labeled a “hate group” by the Southern Poverty Law Center and several immigrant-rights groups. The federation found itself out of favor in Washington during the Obama era, but now several former employees have landed key government immigration jobs, including former executive director Julie Kirchner, who was appointed ombudsman of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

Conditions in Central America

The November decision by the Trump administration to end Temporary Protected Status for 2,500 Nicaraguans who arrived following Hurricane Mitch in 1999 elicited fear and anger among the largest groups of TPS holders — Salvadorans, Hondurans and Haitians. Soon after, the Department of Homeland Security announced that TPS was also ending for 59,000 Haitians. The agency postponed a decision on Hondurans until June to collect more information about conditions in the Central American nation, which was battered by hurricanes in the late 1990s and has struggled to recover.

|

| In January 2001, a magnitude 7.7 earthquake triggered a landslide that wiped out homes and killed hundreds. Photo by U.S. Geological Survey |

They and Salvadorans — the first and largest group granted protection following civil war in the 1980s — are pessimistic about their futures and question the rationale behind the administration’s recent decisions, which were based on the Department of Homeland Security’s finding that the countries had “made considerable progress.” That conclusion was opposite that of the Obama administration 18 months earlier.

“Recovery from the earthquakes has been slow and encumbered by subsequent natural disasters and environmental challenges, including hurricanes and tropical storms, heavy rains and flooding, volcanic and seismic activity, an ongoing coffee rust epidemic, and a prolonged regional drought that is impacting food security,” the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services said when it extended protections from September 2016 to this March. “The regional drought currently affecting El Salvador has made the country the driest it has been in 35 years. The drought is projected to cause more than $400 million in losses from corn, beans, coffee, sugar cane, livestock, and vegetables, resulting in subsistence farmers facing malnutrition and pressure to migrate.”

Arias, Alianza Americas and other advocates are looking to Congress to help them stay and are lobbying heavily.

“Given the actions President Trump has already taken, the only path forwards will be a legislative solution to protect TPS holders from the President’s extreme, enforcement-only, deportation agenda,” U.S. Rep. Zoe Lofgren of San Jose, the top House Democrat on immigration, said in an email to the Public Press.

Legislators from both parties have introduced four bills proposing more permanent legal solutions. All offer a way for qualifying TPS recipients to convert their status. But they differ greatly in terms of the countries targeted, level of priority, requirements beneficiaries must meet and time it would take to legalize.

Lawmakers Take the Initiative

Two bills have attracted attention. Republican Rep. Carlos Curbelo of Florida, the state with the largest concentration of Haitians, led a group of four Republicans and eight Democrats to introduce the Extending Status Protection for Eligible Refugees with Established Residency Act of 2017. Rep. Nydia Velázquez, a Democrat from New York, which also has a large Haitian population, introduced the American Promise Act of 2017. It is favored by many Central American and Haitian advocates because, they say, it includes recipients of both DACA and TPS who come from several countries. Other bills target specific countries and provide another temporary extension, not a permanent solution.

In their search for a solution, Haitian and other groups have organized protests, vigils and rallies, held informational events for TPS holders and visited Capitol Hill. Marleine Bastien, executive director of Haitian Women of Miami, and other advocates see a small but important victory in the administration’s decision to delay deportation proceedings until July 22, 2019, instead of this spring.

|

| Supporters of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals and Temporary Protected Status held a round-the-clock, 22-day vigil outside the White House in August and September. Photo by Allen Majors // San Francisco Public Press |

Alianza Americas and other organizations have written the Department of Homeland Security and members of Congress with their concerns about the dire consequences that ending TPS would have in terms of undermining security, governance and economic stability in the countries TPS recipients come from.

During a nationwide web seminar after the administration’s announcement, Bastien told participants working with Salvadorans, Hondurans and Haitians that Haiti “still suffers food shortages, decrepit infrastructure and other calamities worsened by past and recent disasters.”

TPS holders who are deported or decide to migrate home also face greater danger.

San Francisco has a homicide rate of 6.5 per 100,000 residents, but it’s 59 per 100,000 in Honduras and 81 per 100,000 in El Salvador, among the highest in the world. Trump has vowed to eradicate MS-13, which formed in Los Angeles in the 1980s and today has about 60,000 U.S. members. It has expanded into Latin America and claims an estimated 10,000 members, many deported from the United States. The Obama administration designated MS-13 a “transnational criminal organization,” a first for a U.S. street gang.

Stating Their Case in Court

Besides lobbying Congress, activists are going to court to try to stall or overturn the administration’s actions, much the same as the initial efforts to block Trump’s travel ban targeting several Muslims nations. (The U.S. Supreme Court upheld a modified ban in early December while challenges work their way through lower courts.) The San Francisco-based efforts have delivered proponents one court victory.

An August ruling by the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed that a person granted TPS status would count as a legal entry into the United States. That means TPS holders in California, Nevada and Washington state who are 21 or older and are “immediate relatives” (children or spouses) of U.S. citizens may have family members apply for an adjustment of status that eventually leads to permanent residence.

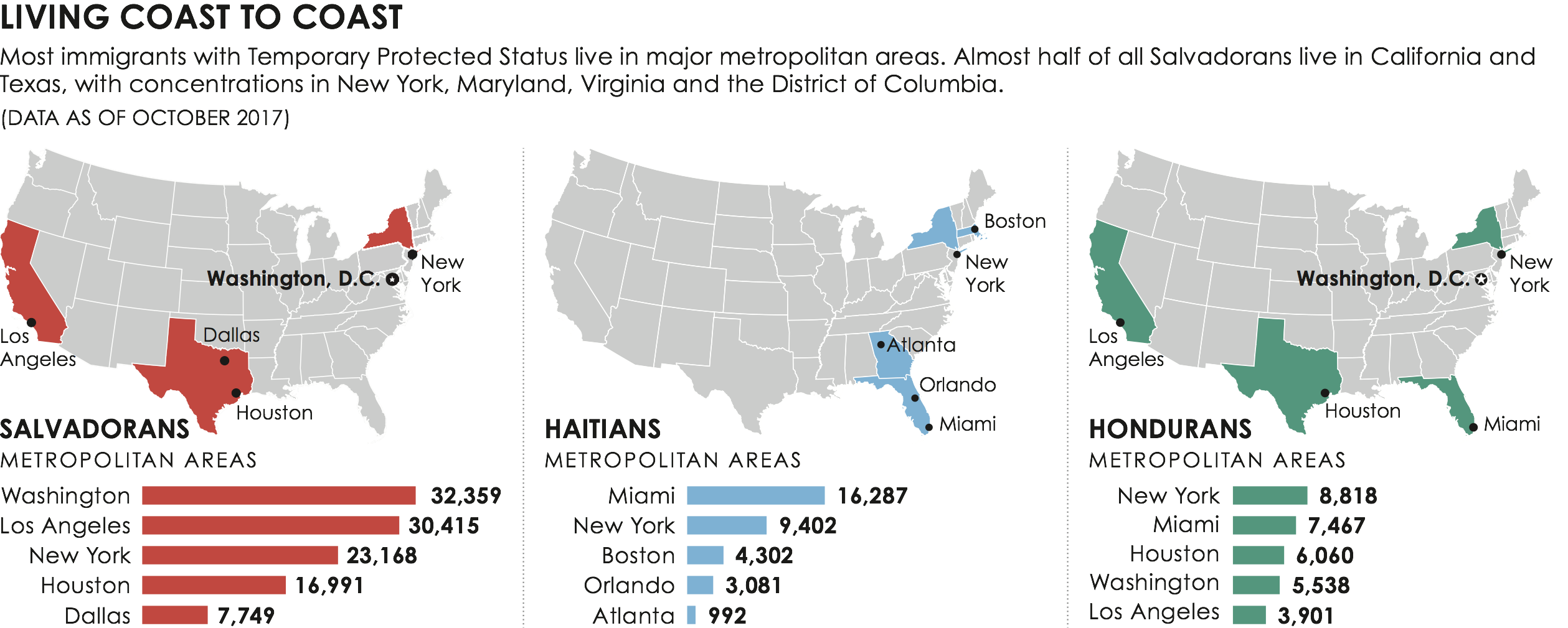

California has 55,000 TPS holders, with the biggest concentrations of Salvadorans and other Central Americans in the Los Angeles area, according to U.S. Census Bureau-based research by the Center for Migration Studies.

But the Citizenship and Immigration Services could not provide detailed local data or say how many TPS holders have secured full legal status to stay. “We don’t have a business need to know how many people from a particular city have been granted TPS,” said Sharon Rummery, a public affairs officer in San Francisco.

|

| Salvadoran TPS holder Rina Valle now lives in Hayward and works in San Francisco. Photo by Anna Vignet // San Francisco Public Press |

The Central American Resource Center is advising the TPS community about its options. Executive Director Lariza Dugan-Cuadra said that thousands of TPS recipients have changed their legal status over several years. She estimated that San Francisco has been home to 10,000 to 15,000 TPS recipients. Since 1996, she said, her Mission District office has processed an average of 600 TPS renewals every 18 months. The numbers have decreased steadily, in part because many adjusted their status through citizenship, residency, spousal petitions and other methods.

The current TPS crisis is only the most recent episode in a saga that for some has kept them in the limbo of temporary status for decades.

The demands of Arias, Martien and others trace their roots to the 1980s, when hundreds of thousands Guatemalans, Nicaraguans and Salvadorans fled civil wars, death squads and other civil catastrophes. The majority of the more than 1 million migrants seeking refuge came to California, primarily Los Angeles and San Francisco — the latter arguably the primary center of political advocacy for Central American refugees in those days.

Those seeking political asylum met almost constant rejection by the Reagan administration — 98 percent of Guatemalan asylum claims and 97 percent of Salvadoran asylum claims. The administration politicized the process by rejecting people fleeing rightist U.S. allies while giving preferential treatment to Nicaraguan nationals fleeing the leftist Sandinista government.

Sanctuary Cities Aid Reugees

|

| A fighter in the village of Perquin, El Salvador, in 1990. Creative Commons image by Linda Hess Miller |

The organizing leading to TPS began shortly after Salvadorans arrived in San Francisco, the first major hub of organizing for that community, in 1980. It was in full swing by 1983, when their efforts led 89 members of Congress to sign a letter requesting that the State Department and the U.S. attorney general grant “extended voluntary departure” to Salvadorans fleeing the war.

The Central American Resource Center and other groups were also the first to secure “sanctuary city” status in San Francisco and Los Angeles to protect refugees from El Salvador and Guatemala from being handed over to immigration authorities by local police, hospitals and other municipal agencies. Federal courts in San Francisco ruled favorably in asylum lawsuits brought by advocates. Together, these and other efforts resulted in Congress granting the first TPS to Salvadorans in 1990. The program was later extended to other groups.

“We’re very fortunate to be in San Francisco,” Dugan-Cuadra said, “because this city has consistently affirmed that we are a sanctuary city, which means all the city institutions — school districts, hospitals and the police — must act in accordance with sanctuary provisions prohibiting collaboration with ICE,” referring to Immigration and Customs Enforcement. “It also includes making legal resources available to get screened. It gives people at least some peace of mind that they’re not in Texas, Florida or other states where ICE agents are waiting for people outside church, in hospitals or at the schools where people pick up their children.”

Fear of Returning to Honduras

One TPS recipient seeking legal and political alternatives is Mariano Guzman, a 55-year-old garbage collector, father of eight and an organizer who came here from Honduras nearly 20 years ago. In November, he and more than 100 others crowded into St. Anthony’s church in the Mission District for an event hosted by the Bay Area Coalition to Save TPS, a network of organizations that includes the African Advocacy Network, RENASE and the Nicaragua Center for Community Action.

“I don’t want to return to Honduras, for two reasons,” Guzman said. “First, because my family is here and depends on me, especially my youngest, who’s only 8 and I haven’t yet told what’s happening. The second reason is that I’ve been critical of the government from here in the United States and I’m concerned that the government will try to kill me like it killed Berta Caceres and other activists.” Caceres, an indigenous leader and environmental campaigner, was shot dead in her home in 2016.

Guzman hears echoes of the 1980s, when he was arrested, tortured and beaten by security forces who suspected him of working with Salvadoran guerrillas near the Honduran border. After a friend in the military helped win his release, Guzman came to the United States to start a new life, but one that still has traces of the old.

“I’ve been ‘temporary’ since I came here after Hurricane Mitch in 1999,” he said. “That’s more than 18 years of not knowing what will happen to me and my family. I’m neither completely here, nor completely there, but in between — and so are my kids. One way or another, this will end and I’m working for it to end happily, with me and my family still living in a country we love.”

Update March 15: This article has been updated to clarify that TPS has been granted to people who are in the United States either legally or without authorization.

This article also appears in the spring 2018 print edition of the Public Press, which can be purchased at select retail locations.