At a packed forum, politicians hashed out where San Francisco would find the money to build housing for the city’s current homeless population

More than a year ago, tech entrepreneur Greg Gopman set the Internet afire with his screed about the grotesqueries he found on the streets of San Francisco, saying that his interactions with the homeless population were ending his “love affair” with San Francisco.

On Wednesday, a forum he organized focusing on solutions to homelessness, was one small step in Gopman’s path to redemption, if not quite romance. His columns on Medium have highlighted his change of heart, and loss of cynicism.

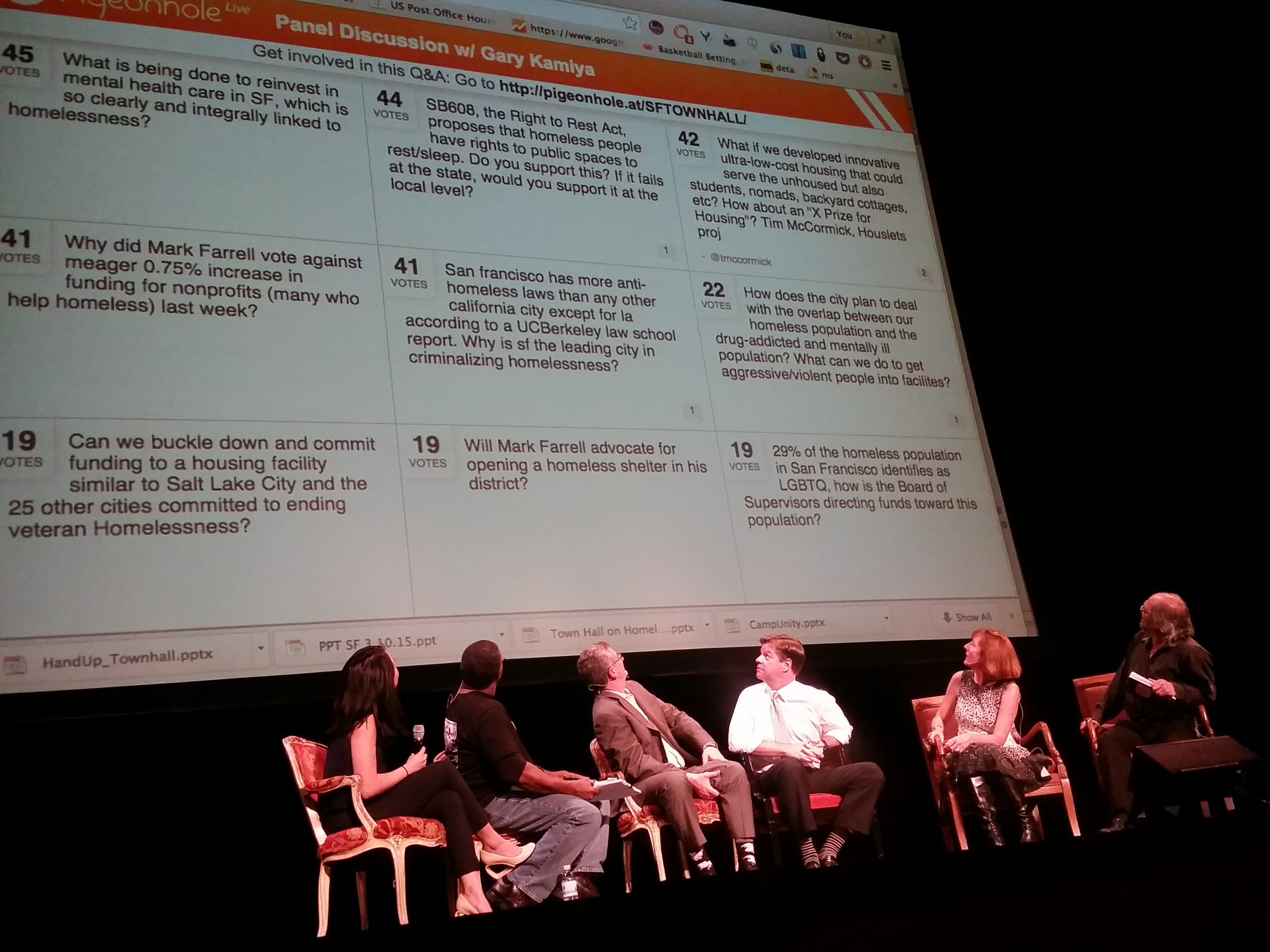

But solving such an inscrutable and persistent problem is easier said than done, as attendees quickly saw at the Town Hall to End Homelessness at the Nourse Theater, in the Civic Center. In spite of speakers’ presentations that showed ways to ameliorate the problem, Supervisors Jane Kim and Mark Farrell argued that without buying or building more permanently affordable homes for today’s homeless population, little could change — and the city needed to act fast.

Buying property now would lock in today’s values, Farrell told the crowd, before they went up even higher, “as extreme as that may seem. But, everyone talk to your parents, they thought the house they bought back in the day was crazy expensive.”

But where would that money come from?

Farrell said that rather than trying to divert meager local funds away from other purposes, San Francisco should go after new, larger government grants, which made up 21 percent of the city’s budget last year.

“We talk about having a dollar amount that’s going to truly make a difference,” Farrell said. “It is at the state and federal level where we are going to get much more bang for our buck. It’s just a simple math game.”

As Farrell spoke, someone in the audience yelled, “Put a bond on the ballot!”

“I don’t disagree with you,” Farrell shot back.

Supervisor Jane Kim pointed out that it had been almost 20 years since city voters approved an affordable housing bond measure. That was in 1996, she said, and by 2000 that was all spent. Similar bonds went to the ballot in 2002 and 2004, and neither passed.

But Kim said she wanted to “go back to the ballot this November, for at least a $250 million bond.” She said the idea had received positive feedback in recent opinion polls.

She also suggested that the city tax sales of luxury condominiums and use the money to build new affordable housing.

The crowd erupted in cheers.

Kim’s last pitch was “a pipe dream,” she admitted, “but I would love philanthropy to give a hundred million dollars to a nonprofit, to just acquire property in San Francisco.”

Again, the response was massive applause.

Joe Wilson, program manager at nonprofit Hospitality House, expanded the idea. If 20 tech companies gave $10 million each, he said, then that could buy 800 units of supportive housing.

But problems remain in the homeless-services infrastructure. As the Public Press reported last fall in its cover story on the unfulfilled promise of a “10-year plan to end chronic homelessness,” the housing-first paradigm of offering homes to the most seriously destitute and ill only works if the city can afford to guarantee housing for those who need help and support them with comprehensive services so that they are stable enough to stay.

The solutions are more complicated than just money, other participants argued. The city needs to support experimental and innovative approaches.

Other Solutions

Rose Broome, CEO of the homelessness charity HandUp, said donors could give money directly to needy individuals, helping them fix a wheelchair or buy a laptop computer, for example.

And founder Doniece Sandoval explained how her company, Lava Mae, provides mobile shower service to the homeless in a converted Muni bus. The company is now retrofitting a second bus, and is fundraising for two more. With all four buses, Sandoval estimated they could provide 50,000 showers every year.

Francis Montgomery, a case manager at the San Francisco Health Plan, attended because he was searching for ways to help fix the intractable homelessness problem.

“I’m not a philanthropist, but I do have some money to give,” he said, adding that he had decided to give to Lava Mae and encourage family and friends to do the same.

The newest idea came from Arondo Cox, a resident and board member of the Camp Unity Eastside mobile homeless encampment in Seattle. About 50 people live in a tent community that sets down stakes for three-month stretches at churches that agree to host them. Nonprofit groups provide free services to residents, such as helping them obtain high school equivalency degrees. Cox said the program moves many people out of homelessness: today, two years after the group first formed, only four of its original members are still living in the camp.

The Navigation Center, which will open later this month in San Francisco’s Mission District, is similar. Up to 75 people will temporarily live at the help center on Mission Street near 16th Street, while city staff try to find them housing. That might mean sending them outside the city through the Homeward Bound program or finding slots in San Francisco’s shelter or supportive housing systems.

Sam Dodge, director of public policy at the Mayor’s Office of Housing Opportunity, Partnership & Engagement, said he was confident that most people who go through the Navigation Center will, ultimately, be placed in housing of some type. “They’ll definitely get an exit — a positive exit,” he said.