Voters approve new waterfront neighborhood, but developer lacks plan to minimize inundation risk

A much-ballyhooed waterfront development in San Francisco could be battered by floods by the end of this century if nothing is done to adapt to sea-level rise, according to new projections by scientists and city planners.

The mixed-use development proposed for the derelict industrial zone at Pier 70, at the edge of the booming Dogpatch neighborhood, is only a few feet above the San Francisco Bay in most places. That is just below the level that city planning documents say could get flooded in the most severe storms by 2100.

Some parts of the property are likely to be underwater permanently, unless the builder adds several feet of landfill to raise the grade. With sea-level rise expected to accelerate this century, the property seems guaranteed to eventually lose the battle against encroaching bay waters.

Without committing publicly to an adaptation strategy, the developer said that it would use engineering to protect the development from rising tides, and added that the project would provide badly needed housing at a time of rapidly escalating housing prices. The bulk of San Francisco’s planned development in the next two decades — 25,000 homes — will also be in other housing megaprojects, at the Hunters Point Shipyard, Parkmerced and Treasure Island.

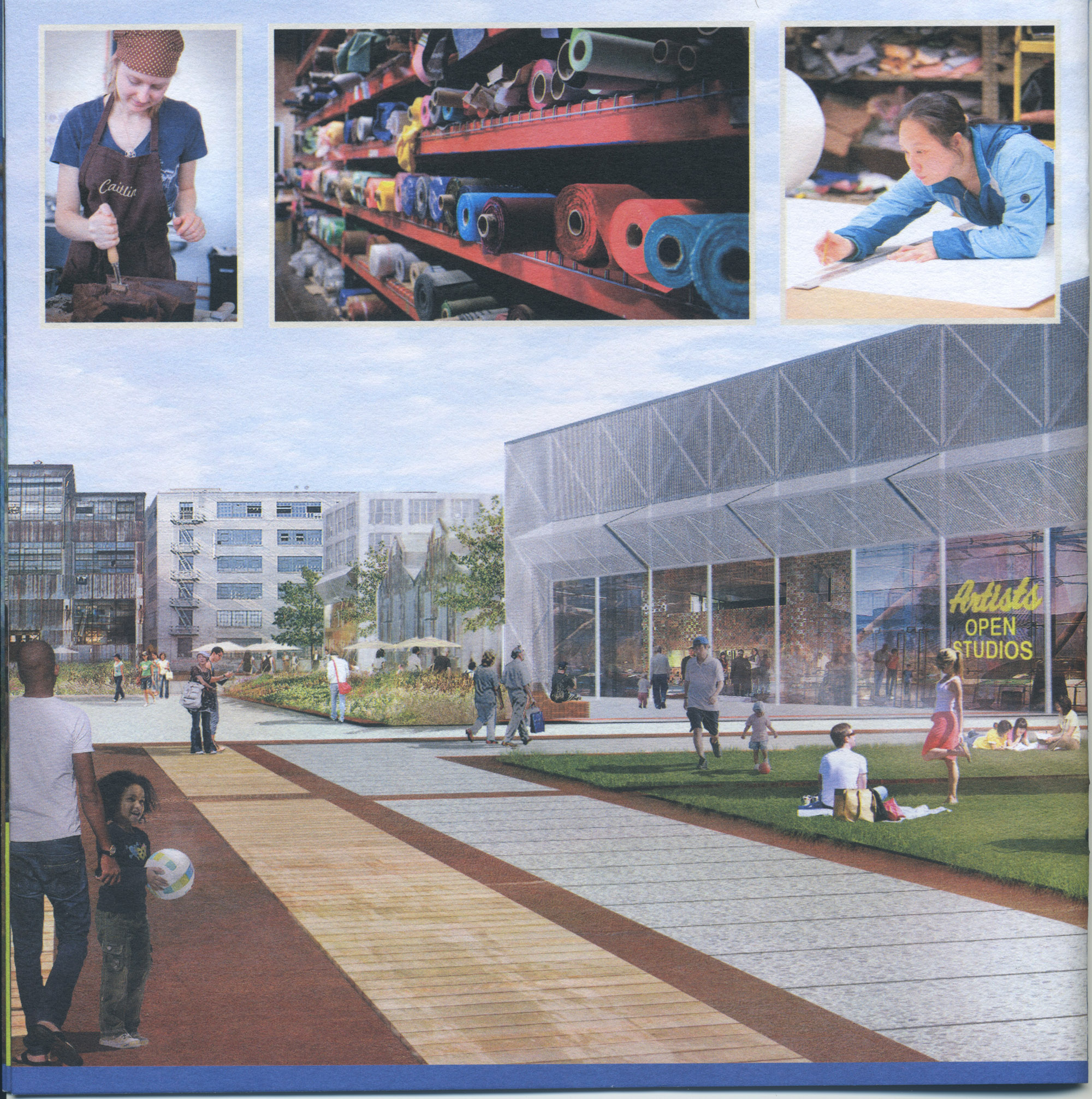

Before the November election, developer Forest City spent $2 million on a public relations campaign that included more than a dozen print mailers to sway San Francisco voters to approve local Proposition F. The measure, which passed with 73 percent of the vote, removed height limits and paved the way for new construction containing retail, light manufacturing and more than 2,000 homes on the site.

The first phase is estimated to cost $242 million. The project won endorsements from nearly everyone important in San Francisco politics: Mayor Ed Lee, former Mayor Art Agnos, all 11 members of the Board of Supervisors and more than 50 prominent community and political groups, including both the Democratic and Republican parties.

It was the environmental seal of approval from the local chapter of the Sierra Club that featured most prominently in colorfully illustrated campaign literature. Becky Evans, chair of the local chapter, said she and her colleagues were impressed with the promise of additional dense urban housing and the company’s extensive efforts at community outreach. Sea-level rise, a concern for the Sierra Club nationally, was not a major consideration in this case, she said.

While Forest City has proven that it can navigate the fractious politics of San Francisco, it must now explain to regulators and city officials how a bayside neighborhood can be constructed safely.

When projecting sea-level rise, scientists measure not just day-to-day tide levels, but also storm surges and king tides, a rare, extreme form of a high tide. Sea-level rise is predicted to accelerate because ocean water expands as it heats and ice sheets are melting in Greenland and Antarctica.

According to some predictive models produced by U.S. government researchers, rare-but-predictable “100-year” storms could crest nearly 6.4 feet above the current mean high tide by 2100. Most of Pier 70 is between 5 and 10 feet in elevation.

Without improvements, large portions of the 28-acre former industrial port complex are likely to be underwater by then.

The predictions come with a great deal of uncertainty, varying by as much as 4.1 feet by the end of the century, depending on the still uncertain impact of melting land ice.

Yet over the last year, San Francisco and regional regulators have arrived at a near consensus: San Francisco Bay is likely to rise 3 feet by 2100. That prediction comes from a yearlong citywide research committee that relied on climate studies by the National Research Council and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

But because the science of sea-level rise is evolving rapidly, even these new projections could be outdated by the time construction is scheduled to begin at Pier 70 in 2017.

“Predictions are in flux, and the scientists are continually and appropriately adjusting,” said Charlie Knox, principal at PlaceWorks, a private land-use firm in Berkeley that produces city and private-sector environmental adaptation plans.

Even before the polls closed in San Francisco on Nov. 4, representatives of Forest City declared victory at the election after-party at the Dogpatch Saloon, and the dozens of assembled supporters erupted into cheers.

Susan Eslick, vice president of the Dogpatch Neighborhood Association, was celebrating the prospect of a new Pier 70 neighborhood. She first heard about Forest City’s plans at one of dozens of conversations the company hosted with community groups. “They did an incredible outreach to community,” Eslick said.

Community groups are pleased by Forest City’s pledges to generate economic activity and expand affordable housing options, including 600 units set aside for low-income families.

But, with increasing awareness across the city and region that the bay of tomorrow will look and behave very differently, placing these assets on the waterfront may increasingly be seen as problematic.

In the run-up to the election, Forest City provided the public with no firm engineering details, but offered a succession of different and sometimes contradictory statements about what it actually planned to do. The campaign website said that the project would protect the area against sea-level rise.

The Yes on F campaign — with a budget came almost entirely from Forest City, according to campaign finance records filed with the San Francisco Ethics Commission — stuffed mailboxes across the city in October with pamphlets covered with collages of images of the future: smiling residents walking dogs and gardening, and bay waters lapping a waterfront lawn a few paces away.

The campaign wrote checks totaling $50,000 to the San Francisco Democratic Party, the Republican Central Committee and the Sierra Club for similar mailings.

Some mailers said that the developers would adapt by “raising the grade to protect against sea-level rise.” In a June meeting with the Bay Conservation and Development Commission, the company told environmental regulators that it planned to raise the level of the land by 2.3 feet. Forest city says it is relying on a prediction of 4.6 feet of sea-level rise by 2100.

But contacted before the election approving the required waterfront zoning change, company representatives said that no architectural plans showing the buildings’ locations, sizes or elevations would be available until the company went through the yearslong planning and environmental approval process.

While executives have said repeatedly that they accepted the science of sea-level rise, it was not clear that the proposals they outlined would be enough to protect the property and residents in future decades.

Asked to elaborate on its strategy for battling sea-level rise, Alexa Arena, Forest City’s senior vice president, said the company planned to “make physical improvements in the immediate term” that could be further adapted with “future improvements,” such as berms, seawalls and wetlands, to absorb storm surges.

She said that no agencies have formally evaluated the site or engineering work, and that the company had not settled on an adaptation strategy. “The exact methodology will be part of the environmental review process and future project planning,” she said in an email.

Over the next two years, Pier 70’s developers will seek approval from at least five agencies, including the Bay Conservation and Development Commission, the Board of Supervisors and the Port of San Francisco, which owns the land. The port awarded Forest City exclusive development rights there in 2011.

Forest City will have to describe in detail to regulators how the project meets the requirements of the California Environmental Quality Act, although the law does not specifically ask for a report on the effects of sea-level rise. The environmental impact report will be available for other local agencies considering approval.

Speaking as an expert on adaptation strategies but without familiarity with Pier 70, PlaceWorks’ Knox said developers and governments have three options to protect against rising seas and storm surges: “You can raise it up, move it or abandon it.”

Forest City could raise the site using acres of landfill. The company submitted early-stage plans to the Bay Conservation and Development Commission proposing to protect the new neighborhood from inundation with a raised shoreline park between the water’s edge and the buildings, according to Joseph LaClair, the commission’s chief planner. He said the review, which is ongoing, would be limited in scope to 50 years of environmental change, whereas other government agencies could choose to peer further into the future to assess the long-term sustainability of new residential and commercial infrastructure.

Arena was upbeat about Forest City’s ability to adapt to an encroaching shoreline, saying it was just one of many challenges that could be overcome with enough investment and the right technology.

Toby Levine, co-chair of the port’s Central Waterfront Advisory Group overseeing Pier 70, said the fall ballot cleared the way to have Forest City help pay for necessary fixes at Pier 70. “If Proposition F had not won, we would have a lot of trouble because the developer has to take on the environmental remediation on his dime,” Levine said. “The port does not have those kind of funds.”

Levine lauded the plan’s inclusion of a strip of parkland along the waterfront for recreation and as a buffer against the bay. She said she trusted local regulators to ensure public safety and wise long-term planning.

“You just have to hope that the agencies that are in charge of protecting the people and the waterfront are in front of the whole movement of water,” she said.

This story was published in the winter 2015 print edition of the Public Press. This is a preview of our coverage for the upcoming spring edition on sea-level rise in the bay.