A team of local biotech researchers may have found a way to avoid using essential food crops for fuel by genetically modifying harmless strains of a bacteria most people associate with human food poisoning.

The result is an extremely expensive fuel — hardly competitive with fossil fuels at $25 per gallon — but marks the beginning of a new look at green energy.

Scientists led by University of California, Berkeley, professor Jay Keasling created an alternative for biodiesel production harnessing E. coli, the bacteria responsible for foodborne illnesses.

A recent study found that E. coli could synthesize production of biodiesel from plant waste, saving the resources — corn, peanut oil, soybean oil or sugar beets — spent on today’s leading “green” fuel, bioethanol.

The results of the study, written by Keasling’s team at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s Joint BioEnergy Institute, were published in the journal Nature earlier this year.

Seizing prime agricultural land to cultivate high-profit crops for biofuels instead of food is a problem for both bioethanol and similar biofuels, said Chris Field, director of the Carnegie Institution’s Department of Global Ecology at Stanford University.

“You want to be careful that you’re not taking away critical food resources while producing biofuels,” Field said.

It’s called “indirect land use change.” Supposedly eco-friendly biofuel shifts food crop production to new land and, ultimately, increase pressure for forest destruction for new agricultural space. The overall result of bioethanol may actually be greater carbon emissions.

The Joint BioEngery Institute team says that the E. coli-synthesized biodiesel takes less energy to produce.

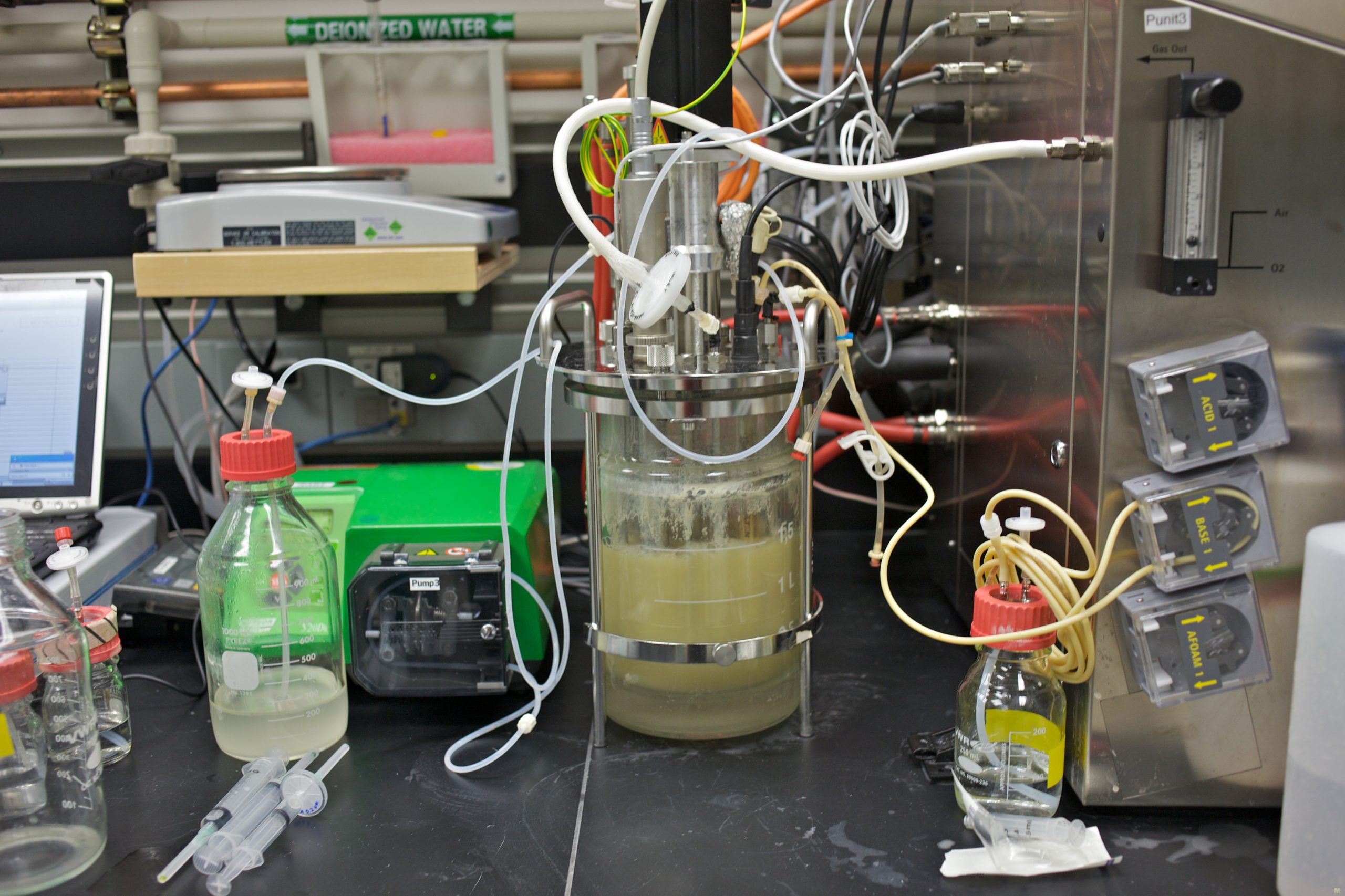

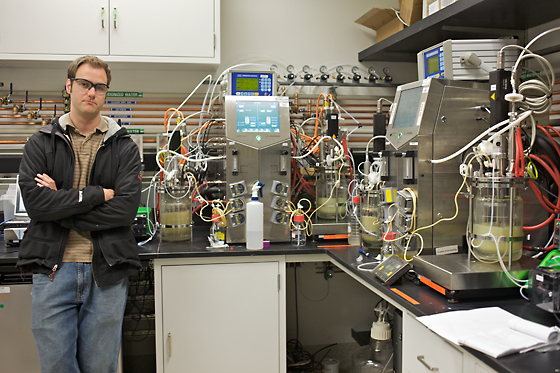

“The entire process can be done with the principle of green chemistry inside the cell,” said Eric Steen, a researcher at the institute and a lead author of the study.

“Biodiesel lowers carbon emissions when you look at the total life-cycle of its production, but is also dependent upon what we’re feeding our E. coli to produce it,” Steen said. “If we’re feeding plant biomass that is directly digested by our bug, the carbon sink is better than that if we’re feeding more processed sugars.”

Steen said bodiesel produced by E. coli is easier to separate than ethanol, which requires an energy-wasting distillation process that releases carbon dioxide. The findings also suggest that biodiesel produced by E. coli could be transported in existing fuel transportation pipelines.

“What we’re producing floats in water — it’s more like petroleum,” Steen said. “It’s easier to distribute than bioethanol.” Bioethanol has the potential to corrode pipelines during transport.

The simplicity of biodiesel production by E. coli could also prove to be cost-effective in large-scale production. “We’re producing a product that is much easier to separate and process,” Steen said. “There’s less energy required and therefore less associated cost.”

Despite having similar properties to petroleum, biodiesel created by E. coli is more expensive than fossil fuels, and Steen said improvements are in the works to make it more feasible for consumption.

Though it will take a few years, Steen said, the next step is to increase the scale of production. One of the partners in the study, the South San Francisco-based biotechnology company LS9, will pursue a business model for producing fuel by varying the process at its Florida plant.

The researchers stressed that their process was safe. They modified E. coli by elevating the bacteria’s fatty acid production levels and introducing genes from other organisms, such as brewer’s yeast.

Though some strains of E. coli cause life-threatening illnesses — for example, the pathogenic strain of E. coli O157 leads to about 70,000 cases of infections every year in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — the researchers said their strains of E. coli are non-pathogenic and safely discarded.

A version of this article was published in the summer 2010 pilot edition of the San Francisco Public Press newspaper. Read select stories online, or buy a copy.