Recession worsens rights gap between rich and poor

At the corner of Turk and Hyde Streets in San Francisco’s Tenderloin, just a few blocks from the glittering commerce and bustling tourism of Union Square, lies a little slice of the Third World that visitors rarely see — unless they go to India or Africa.

In just a minute’s stroll, fashion stores and boutiques hustling Armani and Prada, and European-style cafes peddling panini, cappuccino and white wine give way to adult book stores, liquor markets, pay day loan stores, overnight SRO (single-room occupancy) hotels, drug rehab clinics and bargain-basement deals on crack.

Nestled in the heart of downtown between Union Square and Civic Center (the city’s house of government), the Tenderloin is a chaotic theater of suffering, struggle and survival, performed in the open every day yet eerily separate from nearby neighborhoods that rank among the nation’s wealthiest. Fundamental rights that most Americans take for granted — rights to privacy, housing, health, safety and employment — are starkly absent. Even the post office, that most democratic of government institutions, won’t guarantee they will deliver the mail.

This paradox of normalized, unabashed poverty and extreme separation from the city around it — “we know we’re not welcome outside our neighborhood,” says an elderly man with red sores freckling his face — maintains the Tenderloin’s status as an island surrounded by rivers of cash and opportunity that rarely wash ashore.

This paradox of normalized, unabashed poverty and extreme separation from the city around it — “we know we’re not welcome outside our neighborhood,” says an elderly man with red sores freckling his face — maintains the Tenderloin’s status as an island surrounded by rivers of cash and opportunity that rarely wash ashore.

Amid the deepening economic recession, the ranks of homeless and poor folk are rising while anti-poverty programs are shriveling — posing as a yet unmet challenge to address intensifying poverty. In a city famous for its liberal politics and its pockets of epic wealth — much of which remains despite the tanking economy — the recession has also revived questions of how the public sector can redress the widening chasm between rich and poor.

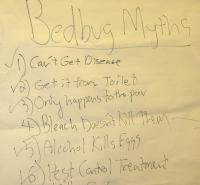

“The biggest problem in the neighborhood, after crack, is bed bugs,” says Joseph Jones, a 70-year-old retired janitor who lives in a Tenderloin SRO. Jones, a 26-year veteran of the Tenderloin and a self-described “amateur social anthropologist” with a Master’s degree in Asian history, is speaking at a meeting of tenant representatives at the Central City SRO Collaborative, a city-funded nonprofit that fights for SRO residents’ rights. Behind the group, butcher paper pasted to the wall lists “Bed Bug Myths,” such as: “can’t get disease,” “alcohol kills eggs” and “only happens to the poor;” and “Facts” like: “drink blood,” “in seams of mattresses” and “7 eggs a day.”

In the middle of the meeting Jones declares, “I just killed a bed bug right here.” Another tenant rep tells of finding bed bugs on toilet seats in his hotel and ongoing resistance by management to get rid of them. Heat kills the bugs, one rep informs the group, to which another responds: “Global warming.” Bed bugs, causing all manner of skin rashes, insomnia and other maladies, are “epidemic” here, says Jeff Buckley, director of the SRO Collaborative. The Department of Public Health “just doesn’t have the manpower to check every hotel.”

The health department and the Department of Building Inspections each have just two monitors tasked with evaluating conditions in roughly 350 San Francisco SROs, of which about 250 are in the Tenderloin, Buckley says.

A host of other indignities pervade Tenderloin residents’ daily lives. Water damage in walls and ceilings is common. Buckley and SRO reps say tenants are forced to ask building managers for toilet paper—“imagine that you have to take a dump and you have to ask the manager for permission to do it.” Broken elevators stay in hazardous disrepair for weeks (“luckily we haven’t had anyone die in an elevator breakdown, but it’s just a matter of time,” Buckley says). During a rather fortunate bathroom visit one evening, a man narrowly escaped a chunk of ceiling, which fell where his head would have been had he been sleeping in his bed.

Then there’s the mail. It never comes.

“The Post Office doesn’t want to deliver to poor people,” Buckley says. “They don’t consider SROs as permanent housing, so people don’t get their mail delivered … all the stuff that anybody else takes for granted, they’re still fighting for.”

In April 2006, following a campaign by the Collaborative and District 6 Supervisor Chris Daly, San Francisco initiated a mailbox ordinance requiring the Postal Service to deliver to SRO residents. But the post office refuses to comply, Buckley says, so a lawsuit may be in the works to enforce mail delivery.

Poverty deepens, aid decreases

As I interview Joanne Harris, a thin, red-headed 39-year-old white woman donning a camouflage sweat jacket, a man crouches by a car a few feet away and fires up his crack pipe.

“He does that right out in the open, like it’s legal, that’s what drives me crazy,” says Harris, who lived on the street for two years before moving into an SRO hotel with her boyfriend. “The police crack down on public drinking, but they ignore the crack.” The recession, she says, has pushed the newly unemployed out of her SRO, into the streets and out of town — “the only people doing well are the drug dealers.”

The streets here are always rugged, but life in “the TL” is getting tougher as jobs disappear and services dry up due to massive city budget cuts.

“It’s getting a lot more tense, people are more stressed,” says Yvette Love, a 40-year-old homeless African American woman in a wheelchair. “There’s a lot more fighting over money and people stealing from each other a lot more.”

Despite its reputation for egalitarianism, the City by the Bay is a town divided — the extreme and entrenched poverty of the Tenderloin butting up against bastions of comfort and extreme wealth. Examined through the lens of two city zip codes, the numbers tell a story of Dickensian disparity.

Consider the gulf between gritty Tenderloin (94102), which includes part of slightly better-off Hayes Valley, and tony Marina/Cow Hollow (94123), just a mile away over the mansion-topped crests of Pacific Heights. Marina residents take home roughly five times what Tenderloin denizens make and nearly twice the city average. In the Tenderloin, the official poverty rate soars over 23 percent, more than double citywide and state levels, while it’s virtually non-existent in the Marina. Despite the Tenderloin’s ballooning poverty, San Francisco boasted the seventh-lowest municipal poverty rate in the nation in 2007, U.S. Census data show.

Rich get richer

Meanwhile, the Bay Area millionaire population keeps growing. According to the 2007 annual World Wealth Report produced by Merrill Lynch and consulting firm Capgemini, 123,621 households in the Bay Area “had $1 million or more in financial assets in 2007, up 10.8 percent from the year before,” the San Francisco Chronicle reported. Some 665 of those resided in zip code 94123, a surprising 116 in 94102. The report projected ongoing millionaire growth despite economic turmoil.

“It’s kind of like Third World and First World,” says Don Simms, who lives in a Tenderloin studio condo and works in a retail store in the Marina.

When the Mayor’s Office of Housing examined 2000 Census data, it found the Tenderloin median household income was less than half the citywide amount. The Tenderloin was home to several of the city’s 33 “areas of low-income concentration,” census tracts where more than half of households had incomes below 80 percent of the city median.

San Francisco sports some remarkable racial, geographic and income divides. A 2006 city Human Rights Commission — HRC — report, citing 2000 Census data, showed that, per capita, whites in Supervisorial District 2, which includes the Marina and other well-off neighborhoods, hauled in $80,256 on average, while Asian/Pacific Islanders in District 6 (the Tenderloin, South of Market and other neighborhoods) took in just $17,074; worse yet, Asian/Pacific Islanders in the city’s ninth district (the Mission, Portola and other working-class hoods) earned just over $10,000.

In 2005, San Francisco’s official homeless count (widely viewed as a serious undercounting) showed an even more stunning poverty divide. Of the 2,497 homeless people counted in shelters, service centers and jails, almost half — 1,232 — were in District 6, while just 22 were found in District 2. While African Americans made up about 6.5 percent of the citywide population, 36 percent of San Francisco’s homeless were black.

Drilling down further, the data reveal severe disparities in wealth, health and education. Nearly half of the Tenderloin’s 964 families with children aged 5 to 17 hovered just above the poverty level in 2000, while just 21 of Marina/Cow Hollow’s 435 such families endured this stress, the HRC found. The Tenderloin zip code ranked among the city’s worst areas for asthma hospitalization rates, while the Marina rested at the comfortable bottom with one-third as many incidents. The HRC also showed a huge education gap: District 6 had half as many high school graduates as did District 2 and just a third of the number of college graduates.

The right to shop and dine in style

It’s a clear warm afternoon, a mellow breeze ruffles the well-manicured hedges next to me and I can see Angel Island resting in the Bay. It’s quiet here on the corner of Green Street and Steiner in the Marina at about 4:30 p.m., at a peaceful remove from the urban crush. In place of rattling shopping carts and angry street disputes, I’m met with the occasional jogger, a multi-task unit of mom-kids-dog-cell phone and, every couple of minutes, a passing Prius, Mercedes, Lexus or Range Rover. Recession?

Underneath the hood, there are in fact signs that the recession has hit the Marina/Cow Hollow area hard. It’s different from Tenderloin hard, though: “I don’t think people are losing their homes here, they’re just not buying dresses,” says Heather Sweeney, who works at Flaunt, a fine women’s clothing boutique on Union Street.

Flaunt is upscale: T-shirts are $60, jeans go for $200, and those dresses run up to $500. But Stephanie Stokes, the soon-to-be owner, says her clientele are “a lot of trickle down from Pacific Heights, women who usually spend $1,000, and they’re not doing that right now.” Sales are falling off, as even wealthy shoppers cut back and others flock to big discount stores.

“Business is sucking right now,” says a retail worker at a high-end men’s clothing store. “Union Street is kind of a train wreck.”

At least 18 Union Street businesses have shut down in the past year (a couple due to retirements), says Leslie Drapkin, co-owner of Jest Jewels, who writes a column for the neighborhood’s monthly Marina Times. With commercial rents falling by 20 percent and small-business stimulus on the way, she’s “edging toward the positive now.” But she adds, “it’s been crazy, everyone is worried … the 30-somethings that have never experienced a recession, that’s our clientele.” Even the rich, she says, are spending less: “The percentages go all the way down the line.”

Her business partner, Eleanor Carpenter, president of the Union Street Merchants Association, is fast-talking and bullish.

“It’s time to move now, time to go — I’m looking to expand,” says Carpenter, sporting stylish thick-frame glasses, a pearl necklace and multiple bracelets draped over her wrist. She’s planning to tap Small Business Administration money for expansions. But the longtime Marina resident acknowledges people there are retrenching: “I don’t think they choose to eat out as much or spend money on Armani or Prada.”

When asked about poverty in the Tenderloin, Carpenter and Drapkin vent exasperation.

“There are all these programs,” says Carpenter, “why aren’t these people using these programs? What’s wrong with them? I guess they’re just collecting their checks? It breaks my heart that they’re in the condition they’re in, but they don’t help themselves.” Drapkin adds, “I’m not one for the homeless programs we have — people need to work hard.”

From raw deal to new deal?

“Every single day, positive and beautiful things happen in the Tenderloin,” says James Tracy, a veteran organizer with the nonprofit Community Housing Partnership, which runs housing and transition programs for homeless people. “All the ingredients are here,” he says, citing activist tenant councils and grassroots organizing groups fighting for better conditions — but he says something bigger and bolder is needed.

“We should have a green municipal New Deal,” argues Tracy, a stocky, bespectacled San Francisco native. “We should be paying people to do community theater, to put solar panels on these buildings. Why can’t they make sure the kids who grow up in this neighborhood learn how to do the sound and lights in the theaters here?” Expanding public sector employment and union organizing rights, too, “would help all workers, shrink the surplus of labor and give working class people more leverage” in the marketplace.

Instead, the kinds of programs that train and employ the homeless are fading from the public landscape even as poverty intensifies.

Meanwhile, the number of homeless in need of help appears to be rising. A survey by the city’s Shelter Monitoring Committee in October 2008 found two-thirds of homeless people were being turned away from shelters. Providers, such as Tenderloin Health, are seeing three times as many homeless as they’re contracted to serve, says Jennifer Friedenbach, director of the Coalition on Homelessness.

“We have this huge increase in the number of people who are poor and a disintegration of the cornerstone poverty abatement programs, such as job training and affordable housing,” says Friedenbach. “It’s the exact opposite approach of what you would want. You would want in this time of recession and increased needs to have this really creative response from city government to turn it around and instead the proposals on the table are to balance this huge deficit on the backs of the most vulnerable San Franciscans.”

“We have this huge increase in the number of people who are poor and a disintegration of the cornerstone poverty abatement programs, such as job training and affordable housing,” says Friedenbach. “It’s the exact opposite approach of what you would want. You would want in this time of recession and increased needs to have this really creative response from city government to turn it around and instead the proposals on the table are to balance this huge deficit on the backs of the most vulnerable San Franciscans.”

Facing a massive $438 million projected deficit, Mayor Gavin Newsom has called for stinging budget cuts that hit the Tenderloin especially hard. The Tenderloin Community Resource Center, the area’s primary resource center for homeless folks, loses its funding as of July 1. The Tenderloin’s main day treatment clinic for the mentally disabled, run out of the Tenderloin Outpatient Clinic, is also getting axed. Shelters at Geary and Polk are limiting access and job training programs are “being pretty much decimated,” says Friedenbach.

The cuts have inspired a feisty response in legislative chambers and on the streets. At a protest in front of City Hall in late March, 700 city workers railed against cuts to health and human services and demanded a different approach.

“People are losing their houses, people are losing their savings, their retirement and it’s the services in San Francisco that help those people in crisis,” said Damita Davis-Howard, president of the Service Employees International Union’s municipal workers local.

Barbara Lopez, a community organizer with the Tenderloin Housing Clinic, which will also face deep cuts, sees a growing contradiction between the federal stimulus and local policies.

“I think the stimulus is about protecting the safety net and stabilizing communities, so why does our mayor feel the need to cut these services?” asks Lopez. “The city leadership has moved to the right of national leadership.” San Francisco, she says, “has this reputation as a very liberal city and socially it is liberal, but I think our dirty secret is that we’re really economically conservative.”

Lopez and others pointed to the mayor’s hiring of 58 new executive managers in the past year (allegedly to the tune of $8 million) and chauffer and limousine services for fire chiefs and others, as symbols of misplaced spending priorities. The unions and advocacy groups propose a blend of alternate cuts and revenue measures to restore vital city services for the poor and working/middle-class San Franciscans.

Indeed, there is a growing push to counter the deficit and the cuts by taxing some of San Francisco’s phenomenal wealth. In February, Supervisor John Avalos called for a special election this summer — as yet unplanned — that would install a gross receipts tax on large firms (it was repealed in 2001), along with taxes on downtown commercial properties and sales.

“If these corporations pay their fair share, we can generate millions that will go towards keeping health clinics, youth and senior services and jobs safe for San Franciscans,” Avalos said in calling for the election.

“The shock of the deficit is being used to make some of the changes that more conservative forces in the city have been trying to make — privatization, reduction in services to the most needy and cutting health services that are primary care services,” says Avalos, who represents a largely working-class district. “We can’t lay off people to get out of this, we have to raise some revenue. We have a lot of wealth in this city, and we have to move it around to alleviate the deficit.”

The mayor’s office has yet to support or oppose specific revenue measures, but press secretary Nathan Ballard insists, “We’re open to new revenue measures, but it’s got to go hand in hand with reform, which includes consolidating departments and streamlining government.” Ballard says the Mayor “stands by his decisions… there are no easy choices. Every cut has a constituency.”

Meanwhile, the coalition has produced alternative budget cuts that focus on capping salaries for upper-level administrators, trimming some high-paid city executives — the number of which has risen dramatically since 2005, according to a Chronicle report — eliminating city limousine chauffers and other bloat.

It remains to be seen whether advocates for the poor and small business groups might act in concert to push for a fairer distribution of wealth and opportunity. Such a coalition could, for instance, press for stimulus monies and revenue streams from new taxes to create new jobs and training programs and to channel small-business supports to the Tenderloin and other embattled areas.

“You can’t have the division that we have,” says Tracy. The solution, he says, “has to be beyond generosity — there has to be improved community hiring … . There’s employment apartheid here. What about City Hall opening its doors to jobs for Tenderloin folks — not just make-work, but make-future?”

Christopher D. Cook is an award-winning journalist and author based in San Francisco. Reach him through www.christopherdcook.com.